It’s long been relatively easy to find financial data about political campaigns online, but that information just got harder to ignore. As Mic noted Tuesday morning, when you search for the names of candidates on Google, you now see infoboxes that include basic stats about how they have funded their presidential bids. Though these charts convey only a fraction of the available data, they’re an interesting entry point into the ongoing national conversation about campaign financing.

In an official blog post, the Google Search team explains that it developed this new feature in collaboration with the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan organization that shares its extensive research into campaign finance on the site OpenSecrets.org. Google had already incorporated other electoral info into search results, including the candidates’ stances on issues and the results of primaries.

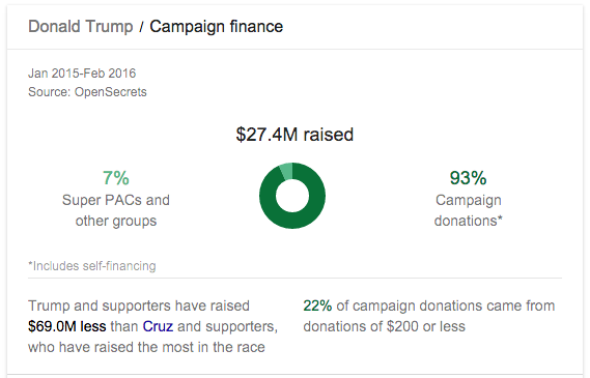

For now, at least, the sidebar financial displays are relatively minimal, showing how much a candidate has raised—and what percentage of that total comes from “Super PACs and other groups.” These charts are refreshingly easy to understand at a glance. It’s striking, for example to see that fully 99.97% of Bernie Sanders’ funding comes from donations.

In its simplicity, this feature can also be deceptive, since it doesn’t separate out self-financing—which makes it harder to immediately parse the financials of Donald Trump, for example—or otherwise break down its two primary categories. While a slightly more expansive accounting is available via a “More campaign finance button,” Google itself still offers only a snapshot of the larger picture. More complete figures are, of course, available via Open Secrets, to which Google links in the infoboxes.

In its blog post, the search team claims that it wants to help users find “unbiased, objective election information.” Here, it’s worth noting that the company’s infoboxes haven’t always been entirely reliable in that respect. As Mark Graham has shown in Slate, because of the ways the company automatically generates information, its default results sometimes inadvertently incorporate political and cultural assumptions. For example, Graham writes, “A search for Abu Musa lists it as an Iranian island in the Persian Gulf. This stands in stark contrast to an Arab view that the island belongs to the United Arab Emirates and that it is instead in the Arabian Gulf.”

Google’s choices about what to show in its presidential candidate search results are sometimes puzzling. When I searched for John Kasich, the “On the issues” box offered a simplified take of his “Economy and jobs” stance by way of a brief quotation from the Keene Sentinel. In the same spot on Donald Trump’s page, however, I got a synopsis of the businessman’s positions on immigration, here by way of an excerpt from the Hill. Why these issues for these candidates from these sources? There’s no easily available way to tell.

Graham has written that Google is often opaque about where it’s pulling its information from. Among other things, this can create the illusion of definite facts, even when none are available. In that regard, at least, it’s great that the company’s algorithm is citing its sources here. Nevertheless, it’s still not clear why it’s displaying what it’s displaying, a situation that threatens to actually create informational asymmetries about candidates where none would have existed otherwise.

The data may, however, be somewhat more reliable where candidates’ fundraising is concerned. Because it’s drawing all of that information from the Center for Responsive Politics, there’s no question of its provenance. And because Google is showing the same type of information for each candidate, it’s easy to compare them. What’s more, campaign finances—unlike, say, the ownership of contested islands—are relatively easy to grasp in objective terms, which makes them a good fit for the Google’s infobox format.

There is, however, another more pressing question about the usefulness of this new feature. It primarily works when you search for a candidate’s name, with no other terms attached. The system is smart enough that it will present financials if a user looks for, say, “Donald Trump money,” but won’t offer it if they go looking for something like “Donald Trump twitter.” This means that only those looking for the broadest possible information will encounter the company’s search boxes, unless they’re after the very thing those boxes show. Nevertheless, it still promises that some potential voters will be more informed than they would be otherwise.