When it comes to cybersecurity, we spend so much time talking about the future of Internet threats—how terrifying and destructive they could become, what we should do about them, why they’re getting more dangerous every day—that it can be easy to forget about their past. Enter the Malware Museum, a site launched last week by Jason Scott with help from Mikko Hypponen through the Internet Archive. It attempts to re-create and commemorate some highlights from the library of malicious programs distributed in the 1980s and 1990s, when computer-based threats were still in their infancy.

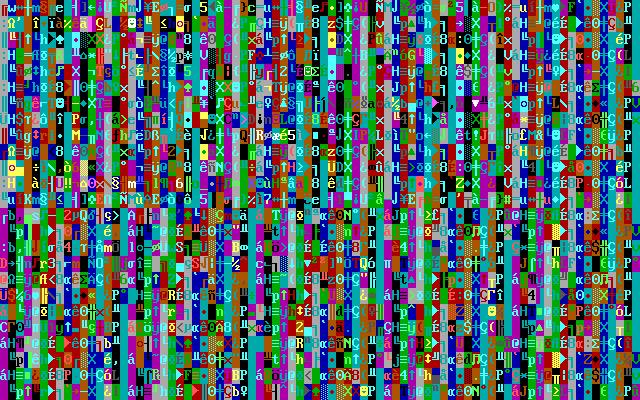

There is something strangely soothing and hypnotic about the collection, which allows viewers to simulate the experience of having their computers infected by the featured pieces of malware by showing the animations that would appear on the screens of infected machines. (Needless to say, all of the malware in the museum has been effectively neutered—you can experience what you would have seen on the screen of an infected computer, but your computer will not actually be infected by viewing those simulations.) The animations can be transfixing—take, for instance, the CRASH checkerboard pattern of characters and colors, or the aptly named LSD rainbow shifting shapes—or ominous, like the scrolling countdown in NAMELESS, or just plain silly, as in the MARINE animation of a small sailboat going back and forth, or the paean to Italy offered by ITALIAN.

In this format, with their destructive capabilities removed and the ability to pause or close out of them at any point—rather than being forced to stare helplessly as your screen flashes text or patterns of bright colors at you—many of the viruses seem more like primitive pieces of digital artwork than threats.

How benign everything looks—and how distinctly dated. Not just the fonts, graphics, colors, music, and cultural references (though those are, indeed, dated) but also the notion of malware as a lark—a vehicle for silly pictures and dumb messages and corny animations. Nowadays, we tend to talk about online threats only in the most apocalyptic terms: We worry about power grids being shut off, or banks being compromised, or our computerized cars running away with us.

In most fields, artifacts that are only 20 or 30 years old would probably not be considered museum-worthy, but when it comes to malware, the ’80s and ’90s really do feel a little like a long-lost era that’s been nearly obliterated in the present day—a period in need of conservation. So it’s not hard to see why the site has already drawn more than 100,000 visitors, many of them, no doubt, attracted to the site’s evocation of the simpler times of the early Internet and the laughable bits of mischief that were perpetrated on it.

Not every piece of malware from the 1980s and ’90s was adorable, of course—and not even all of the featured pieces in the museum were harmless when active. But even at their most malicious, they were still a far cry from the kinds of threats we worry about—and witness—now.

That’s in large part because 30 years ago there was very little money online—for the most part, people weren’t going online to summon cars or buy shoes or deposit checks or pay bills. With the rise of the commercial Internet in the late 1990s and early 2000s, online crime became big business and began attracting the sorts of serious-minded, organized criminals who were out to make money, not just the tech-savvy mischief-makers out to concoct cute animations and wreak havoc.

Nostalgia for the malware of the 1980s and ’90s isn’t just about regretting the loss of a particular brand of computer viruses or even a particular breed of cybercriminals—it’s also, in its way, about regretting the loss of the low-stakes Internet. It was an Internet where nothing terribly important was going on in the first place, so there was only so much to fear from it when something went wrong.

And of course, for the most part, we don’t actually want that Internet back—and even if we did, it’s not clear we could have it—because being able to summon cars and buy shoes and pay bills online is incredibly, wonderfully convenient. High-stakes crime and threats are part of the price we pay for having an Internet that’s more than just an academic or recreational pursuit.

All the same, it can be a little startling to go back through the archives of malware written not so long ago and realize how unrecognizable much of it now looks. Not just because the code and the people who were writing it—along with everything and everyone else in technology—got faster and better and more effective but also because they were driven by very different motivations than our modern-day online enemies.

Browsing through the newly launched site and realizing how much has changed in such a short period—how radically and irrevocably the landscape of computer security has been altered—you wonder how dated our current threats will look 20 or 30 years from now and what will have replaced them.

Can you picture the malware museum of the 2000s and 2010s? The exhibits for Conficker, Stuxnet, Flame, Zeus; the brief descriptions of the size and scope of each, how much damage was done, the sums of money lost, the number of victims affected. Will people browse through nostalgically and say to themselves: “How quaint, how adorable, can you believe they thought that was malware?”