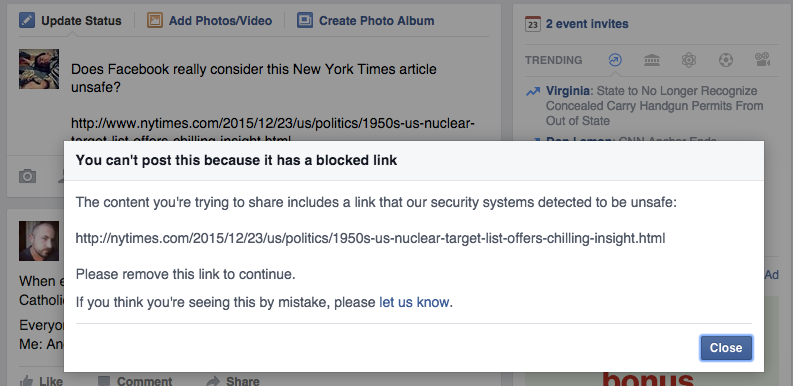

When atomic weapons historian Stephen Schwartz tried to post information about 1950s U.S. nuclear targets to Facebook Wednesday, the site stopped him. “The content you’re trying to share includes a link that our security systems detected to be unsafe,” an automated error message announced. Here’s the strange thing: Schwartz—who pointed out the oddity on Twitter (where Washington Post journalist Dan Zak noticed it)—wasn’t sharing state secrets. He was posting a New York Times article.

It’s not immediately clear why Facebook blocked the story—a fascinating and chilling historical narrative woven from publicly available information—or even whether the block was algorithmic or manual. At first, Slate colleagues told me they were able to link to it through the Facebook widget on the New York Times’ page, but attempting that method now generates a message that reads, “The server found your request confusing and isn’t sure how to proceed.” As some have noted, posting the mobile version of the article appears to work, and other articles about nuclear targets failed to generate the same issues. All this suggests that Facebook isn’t really taking issue with the article itself, so what exactly is going on here?

Facebook is no stranger to censorship of various kinds, and it’s hardly the only company in that game. As Hyperallergic reported earlier in December, the Electronic Frontier Foundation has an entire site designed to help monitor censorship across social media platforms. Facebook itself has also meddled more directly with links, most recently and notoriously for barring all links to—and discussions of—a nascent social network called Tsu, possibly because its business model resembles that of a multilevel marketing scheme.

Wednesday’s incident doesn’t appear to be the same sort of blackout as the one Facebook has orchestrated against Tsu, even if the effects are similar insofar as it closes off important possibilities for conversation. The issue is that Facebook makes it difficult to determine what’s gone wrong and where. Ordinarily, when users complain about the “unsafe” link message they’re told to run their problematic links through Facebook’s publicly accessible debugger. Try that here, however, and you’ll generate yet another error message: “An internal error occurred while linting the URL.” If all this seems puzzling, you’re not alone. When we reached out to Facebook for comment, a representative expressed confusion, writing that the ops team was “not aware of any issue,” but promising to look into it.

Again, whatever’s going on here clearly isn’t willful censorship. What’s troubling is the lack of transparency. The more powerful Facebook gets, the more such erratic quirks threaten to shape our everyday experience. At the very least, the company would do well to elaborate on what they mean by “unsafe.” Without providing further details, the site is effectively infantilizing its user base. Even if Facebook eventually explains what happened with the New York Times article, the initial mystery is a potent reminder of who really controls our ability to share information.