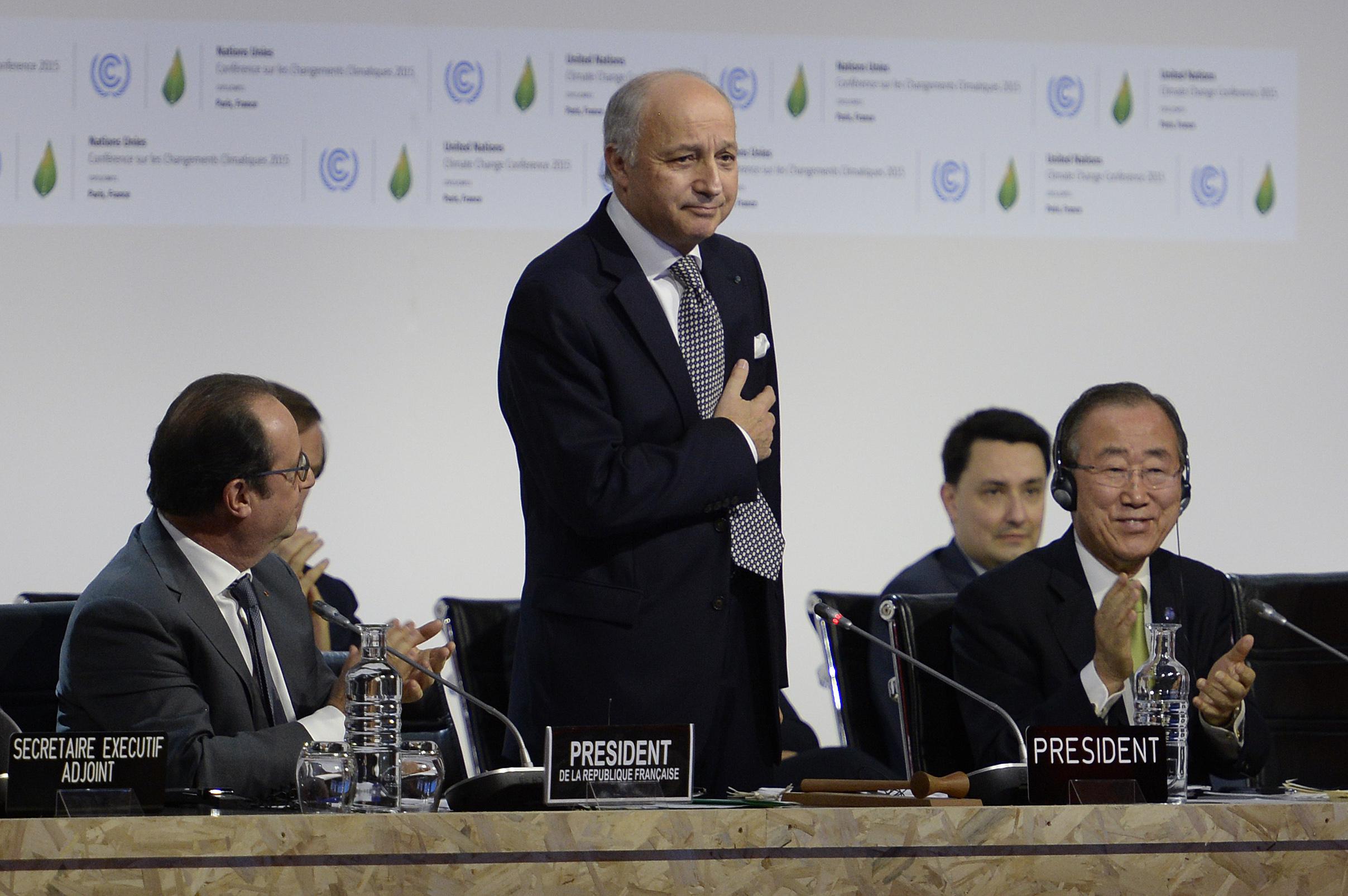

Over the weekend, world leaders unanimously signed on to an ambitious set of climate accords. While this is cause for celebration, putting these agreements into effect may be difficult, not least of all because they outline such ambitious goals. Among the most daunting proposals is the obligation to cap the global average temperature at less than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. Admirable as this target is, hitting it may mean adopting controversial—and largely unproven—technologies.

As Eric Holthaus has explained, if we have any chance of remaining within that 2-degree window, developed countries will have to dramatically reduce their carbon emissions, bringing them down to almost nothing. Such extreme changes would not, however, be enough: Even if we were to completely stop producing greenhouses gasses today, it would take thousands of years for the Earth to return to its preindustrial state.

The AFP notes that if we really hope to hit that goal, we will therefore have to find ways to remove CO2 from the atmosphere, not just stop adding more. This will almost certainly mean embracing geoengineering, a catchall term that describes the conscious and deliberate transformation of the Earth’s climate, typically by technological means. Though some speak of it as if it were fringe science, it plays an increasingly central role in mainstream conversations, thanks in no small part to a comprehensive pair of reports by the National Academy of Sciences—which prefers the less ominous sounding phrase climate intervention—released earlier this year.

Significantly, the Paris accords already contain a nod to such interventions, encoding it in the awkwardly worded recognition of “removals by sinks of greenhouse gases.” Here, a sink is a system that pulls gasses out of the air and sequesters them. There are many ways of producing carbon sinks, including the time-honored tradition of growing forests. But this approach is a slow one, especially in relation to the timeline that the Paris accords establish. In effect, then, this phrase could be read as an acknowledgment of the need to try out other techniques—and to do so posthaste.

A number of geoengineering technologies are already within reach, though some are more promising than others. Of these, the most troubling—but also the most immediately feasible—is known as solar radiation management, which would involve reflecting a portion of sunlight back into space. Though it could dramatically and cheaply reduce temperatures with astonishing speed, it would do nothing to pull CO2 out of the atmosphere. This means that it addresses one effect of climate change without ameliorating its causes, an imbalance that has inspired considerable hand-wringing from climate scientists.

Fortunately, there are other approaches to geoengineering, including some that would filter carbon dioxide by mechanical means. Often described by technical-sounding terms such as free air capture, these technologies are still in their infancy. Expensive and inefficient, they don’t yet present a workable solution to our global crises. But the weekend’s diplomatic developments may provide companies and countries alike with the inducement they need to take the next steps. As Holthaus writes, negotiations took “a ‘build it and they will come’ approach.” More effective geoengineering technologies may be one of the things that arrive in their wake.