On Friday the FBI classified the San Bernardino shooting as “an act of terrorism.” Tashfeen Malik and her husband, Syed Rizwan Farook, don’t seem to have been in direct contact with ISIS, but the extremist militant group called the couple “supporters” on Saturday. “At this point we believe they were more self-radicalized and inspired by the group,” one anonymous official told the New York Times. According to officials, Malik had posted a bayat, or pledge of allegiance, to ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in a Facebook post.

On Sunday, during an interview with George Stephanopoulos on This Week, Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton said that the government is “going to need help from Facebook, and from YouTube, and from Twitter. They cannot permit the recruitment and the actual direction of attacks or the celebration of violence by this sophisticated Internet user. They’re going to have to help us take down these announcements and these appeals.”

However, in the case of the post from San Bernardino attacker Tashfeen Malik, it seems that’s exactly what happened. Malik posted her ISIS pledge on an account with a different name, and Facebook says it removed the profile because it violated the site’s community standards by praising and promoting terrorism. Officials told the Los Angeles Times that Malik posted her allegiance comment shortly before she and her husband initiated the attack on Inland Regional Center. And FBI Director James Comey said that the couple’s digital presence before the attack was “nothing of such a significance” that the FBI would have flagged them in advance.

Nevertheless, the situation with Malik is giving new life to the debate about whether social networks should be legally required to report suspicious posts or activity to law enforcement. A provision of the 2016 Intelligence Authorization Act approved by the Senate Intelligence Committee at the beginning of July would have required tech companies to report “terrorist activity” to law enforcement. “What they do now is simply terminate the account of the person who is plotting the attack,” Richard Clarke, a former White House counterterrorism official and ABC News consultant, told the network. “It is very unlikely today that a social media company would turn around and call the police.”

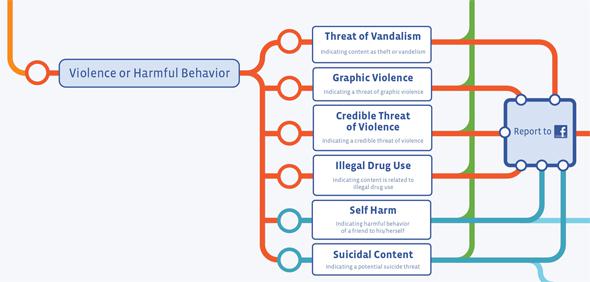

But critics pointed out that the bill did not offer a definition of “terrorist activity” to guide social networks. And the Washington Examiner reported on July 9 that FBI Director Comey was actually only lukewarm about the bill. He called it an “interesting idea” but added that tech companies are “pretty good about telling us what they see.” Indeed, Facebook has consistently said that it reserves the right to “refer issues to law enforcement.” Furthermore, Monika Bickert, Facebook’s head of policy management, told Reuters in a statement: “We share the government’s goal of keeping terrorist content off our site. Our policies on this are crystal clear: we do not permit terrorist groups to use Facebook, and people are not allowed to promote or support these groups on Facebook.”

On July 28, Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., placed a hold on the bill because of the vague definition of “terrorist activity” in the social media provision. “I haven’t yet heard any law enforcement or intelligence agencies suggest that this provision will actually help catch terrorists, and I take the concerns that have been raised about its breadth and vagueness seriously,” Wyden said in a statement. “Internet companies should not be subject to broad requirements to police the speech of their users.”

Furthermore, legally requiring that social networks surveil users can lead to censorship creep. Or as Emma Llanso, who runs the Free Expression Project at the Center for Democracy & Technology, put it in a July blog post, “Turning all communications intermediaries, who are today’s stewards of our electronic papers and effects, into informants for the government flies in the face of Fourth Amendment protections.” (The debate over social networks and extremists is a bit like the ongoing discussion about giving law enforcement “backdoor” access into encrypted data. During his Sunday evening address about terrorism, Obama seemed to refer to encryption when he said, “I will urge high-tech and law enforcement leaders to make it harder for terrorists to use technology to escape from justice.”)

As politicians and law enforcement scramble to secure the United States against terrorist attacks, there is a strong need to know what’s going on around the country. But this must be balanced by an awareness of the fine line between information-gathering, surveillance, and censorship.

In her interview with George Stephanopoulos on Sunday, Hillary Clinton said, “I know what the argument is from our friends in the industry. I respect that. Nobody wants to be feeling like their privacy is invaded. But I also know what the argument is on the other side from law enforcement and security professionals.” If Clinton is uniquely positioned to see both sides of the debate, then she should know that compelling social networks to act as dragnets is not the solution, especially if they’re already willing to develop internal standards.