In February 2004, Nicholas Merrill—who owned a small Internet service provider at the time—was served with an administrative subpoena called a National Security Letter, or NSL. He was asked to turn over a client’s electronic metadata to the FBI without any judicial oversight. Because the NSL was accompanied by a gag order, Merrill was forbidden from ever mentioning the request, even to the person targeted by the FBI—who, by the way, was not even suspected of a crime.

Rather than complying with the unconstitutional request, Merrill went to court with the assistance of the American Civil Liberties Union. He spent more than a quarter of his life fighting challenging the legality of a Patriot Act provision that allows the FBI to issue NSLs in the first place and then fighting for the restoration of his First Amendment rights. The gag order was only partially lifted in 2010. In August of this year, a judge ruled that Merrill could disclose what he’d been asked to turn over to the FBI if the government did not appeal within 90 days. That deadline passed on Nov. 30, and Merrill is now free to discuss the type of information the government sought 11 long years ago.

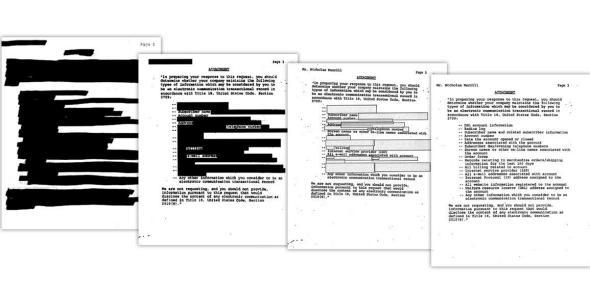

Image by the ACLU

A 2008 Department of Justice legal opinion said that the government was asking for “only those categories of information parallel to subscriber information and toll billing records for ordinary telephone service,” but the list Merrill received went far beyond that. He was asked to provide the government with the individual’s complete Web browsing history (which includes search history), the IP address of anyone he or she’d ever corresponded with online, and records of all online purchases. The letter also asked for the radius log, which Merrill believed to include cell site location—essentially turning their mobile device into a location-tracking device. (Although the FBI says it is not currently gathering location data, it reserves the right to request it in the future.) Merrill was also asked to provide anything else he considered an “electronic communication transactional record.”

Although he declined to disclose the target of the original NSL for privacy reasons, Merrill has his own theory about why he or she was targeted. “I had some ideas because I know the person, and they were being harassed, and [the FBI was] trying to strong-arm them into becoming an informant,” Merrill said via encrypted chat. “I thought it was ludicrous from the beginning. I thought the FBI was using an NSL because they didn’t have what they needed to go to a judge.”

There have been more than 400,000 NSL requests between 2003 and 2011, but Merrill believes that many more people are affected. “If they issue about 50,000 NSLs per year from 2002 to 2012, that is 500,000 NSLs. If you assume that each NSL relates to one person then that’s 500,000 suspects for counter-terrorism or counter-espionage. In a country of 300 million people, that is already 1 in 600 Americans. I find the idea that 1 in 600 Americans could be suspected of terrorism or espionage hard to buy,” he says. Audits from the Department of Justice inspector general show that NSLs have been used on first- and second-degree contacts of people of interest. The inspector general’s report also states that NSLs often ask for bulk data. Says Merrill:

One of [the NSLs] got a list of everyone that went to Vegas over New Years Eve one year. Another few NSLs got the entire phone billing records of 11,000 people. So then you realize that you cannot assume that each letter affects just one person. Now it’s one in 300 Americans? Or one in 100 Americans? Who knows? We are reduced to guessing because we have so little actual data. Which brings us back to the gag orders and secrecy, and how that leads to unaccountability.

Because NSLs are shrouded in secrecy, it’s hard to tell whom the information is currently being shared with, what the retention policy is, and whether data is ever purged if a person is never accused of wrongdoing. But in 2007, ACLU policy counsel Michael German, a former FBI special agent, pointed out that “information received through NSLs is indefinitely retained and retrievable,” even if the subject is found to have posed no terror threat. Data is shared with the intelligence community, across government agencies, and even with foreign governments.

Some companies have fought back against NSLs by publishing warrant canaries—making public disclosures that they have not received government data requests on a semi-regular basis. In theory, this will allow companies to track gag orders indirectly by seeking a judge’s opinion if the government attempts to force that company to issue a statement saying it hasn’t received an NSL even when it has.

“Warrant canaries are cool because they are pro-business civil disobedience. People want to find creative ways to resist, and there are not that many options,” Merrill says. But, as he notes, warrant canaries don’t deal with the underlying issue.

“The real problem is the government seizing data in violation of the Fourth Amendment,” he says. He recommends that companies try to file facial challenges, which test the constitutionality of the law itself. And in fact the Electronic Frontier Foundation is currently representing two unnamed California ISPs fighting back against NSLs. Although Merrill’s New York case is not legally binding in California, an EFF attorney told U.S. News that “the decision could be influential in that it shows that a gag can be lifted without harming national security.”