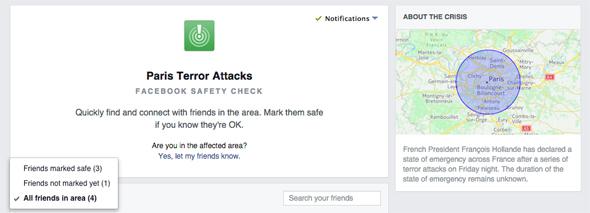

With Paris in crisis on Friday evening, people were scrambling for news, not just about what was going on, but to find out if their friends and family were safe. And Facebook’s Safety Check feature, which it first introduced in 2014, quickly emerged as a practical and valuable tool. All Facebook users in Paris had to do was answer the question “Are you safe?”

It’s a simple question, and responding to it can help to reassure our personal networks and communities during times of uncertainty. But it’s also a deeply personal question. Usually we’re asked something like that verbally—by a person who cares about us, or by a person whose profession embodies societal care, like a first responder or a social worker.

Facebook already asks users, “What’s on your mind?” every day through its status field, and the service collects tons of personal data about each of its users. But to have a multibillion-dollar corporation ask indivuiduals one of the most fundamental questions of life adds a new degree of intimacy to the relationship between social networks and their users. Facebook, with its more than 1.5 billion users, is well-suited for the task of collecting individual safety information. It has the right infrastructure in place. But the more we rely on it, and allow it to reassure us in moments of chaos, the more we need to scrutinize the power we are giving it.

We all know how upsetting uncertainty and a loss of control can be. Even when people are waiting for trains and buses, there is a noticeable psychological difference if a countdown clock is available to tell them how long it will be, so they don’t have to wait anxiously without a time estimate. Safety-check features tap into the same emotions. You may know people who don’t use social media or who probably aren’t going to bother marking themselves as safe during a crisis, but just getting confirmation from anyone you know feels good. These updates—that someone you know is simply OK—read as individually tailored good news amid the stream of impersonal and unpredictable dispatches that emerge out of an emergency situation.

When Facebook first released Safety Check, my Slate colleague Will Oremus wrote, “I can’t imagine it will be so widely used that your loved ones will panic if they don’t see your name on there in the event of a disaster.” But the profound reassurance people get from the service is, to my mind, exactly what will push Safety Check toward ubiquity. And that means Facebook will take on a profound responsibility.

Facebook’s service isn’t the only one out there, of course. Other check-in features like Google Person Finder offer alternatives for non-Facebook users. But you can see how things could start to get complicated. What if a person registers that they are OK on one service but not another? What if someone marks someone else as safe (a useful option that Facebook provides) based on inaccurate information? And how will tech companies decide when a crisis is big enough to merit activating these features?

When personal-safety information is something that social networks are hosting, people feel obligated to participate far beyond the social demands they usually feel compelled to participate in. And although savvy Internet users value a diversity of choice and are suspicious of any network that becomes too monopolistic, it’s obvious why safety check-ins are more effective when information is centralized. Facebook and services like the French government’s missing person report forum are offered by two very different types of organizations. But as our reliance on these check-in services grows, it may simply make the most sense to rely on a company like Facebook—with its massive reach and sometimes profit-driven priorities—to be the venue for our safety check-ins.

The more we feel ourselves turning to these features, the more realistic it seems to imagine that one day they’ll just be on all the time—so if there’s a traffic accident or building fire in a community, people can proactively indicate that they are safe.

Depending on the disaster, will people start getting targeted advertising on their social networks for fire insurance or PTSD treatment after a couple of days? And what if you don’t want to answer the question “are you safe?” when you’re lying in a hospital bed after a trauma? The question of how these services will evolve shouldn’t imply that they’re not worthwhile. In fact, it is their value that makes exploring their implications so important. Our status updates may feel like tiny, ephemeral acts, but when it comes to these particular notifications, we should be aware of their gravity: They’re literally updates on life and death.