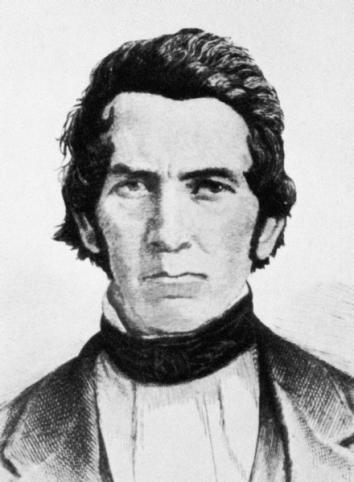

In the early 1800s, Thomas Davenport, a poor, young, self-taught blacksmith in Vermont tinkered with magnets to create, and eventually receive a patent for, the first electric motor. Nearly 200 years later, middle-schoolers in Albemarle, Virginia, are tinkering with modern 3-D–printing technology to reconstruct and model his historic invention.

This isn’t the sort of lesson that you would find in a standard middle-school science class. Albemarle County Public School District—in collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution and the University of Virginia—is creating this project-based curriculum with nearly $3 million in support from the Department of Education’s Investing in Innovation, or i3, grants. With these competitive grant dollars, the district is developing all of the necessary materials: instructional materials and assessments; detailed directions with figures, photographs, animations, and 3-D–printer files; and even professional development materials for teachers.

According to Chad Ratliff, assistant director of instruction in Albemarle, students today can’t learn about the inner workings of objects they interact with daily, like their iPhones, by just opening them up—they’re too complex. Teaching engineering through historical inventions allows students to break down and understand the basic concepts, while integrating STEM learning with history.

This investment is great for the students of Albemarle, but what about those enrolled in other school districts across the country? Will students, in say, Davenport’s hometown of Williamstown, Vermont, benefit from these kinds of learning experiences?

With little more than a year left in the Obama administration, the Department of Education is taking steps to make sure these kinds of educational materials, developed through public investment, don’t only benefit their grant recipients. The department has proposed that, for its competitive grant programs at least, all grantees would be required to openly license the educational materials they develop. By changing the default to open, the department is betting that it can increase the supply of high-quality open educational resources so that other educators can use and improve upon them.

Open educational resources, commonly defined as “resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others,” have gained traction over the past decade in the field of education, with federal agencies, states, and colleges already exploring the possibilities of open licensing.

It makes sense that resources created with public money should be free for the public to use. And the department sees the potential impact as threefold. First, an open-licensing requirement would allow for more strategic investment, potentially reducing the need to fund duplicative projects. Second, experts in the field would have the ability to improve upon the resources created through its initial investment. Most importantly, the department emphasized that this move could help level the playing field for low-income districts, “promoting equity and especially benefiting resource-poor stakeholders.”

The announcement comes with a few caveats, however. While the Department of Education doles out about $67 billion annually, the vast majority of those dollars are dedicated to formula grants to states and direct grants to individuals—two types of funding that are not covered by the newly proposed rule. Competitive grant funding accounts for just a fraction of that spending—a bit less than $3 billion annually. (The department does not maintain a comprehensive list of annual competitive funding; this estimate was calculated by New America, where I work, based on the latest Department of Education budget information. New America is a partner with Slate and Arizona State in Future Tense.)

That nearly $3 billion, however, supports the development of lessons and instructional plans, professional development resources, and other teaching and learning materials that benefit learners from early childhood through graduate school. Funds go toward supporting the instruction of students from diverse backgrounds, including indigenous groups, migrant students, and students with special needs. Additional programs support literacy, STEM, physical education, arts, and early learning programs. Others target drug prevention programs, student counseling efforts, and efforts to help students navigate the transition from high school to higher education.

The department has already bet big on the promise of open. In partnership with the Department of Labor, it tried out the open licensing requirement on the $2 billion Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training program, which provided funding for the development of career training programs. Further, the department’s First in the World grants—which support innovative solutions to increase students’ persistence and completion of college—requires all content produced to carry an open license.

Albemarle’s i3 grant won’t be affected by this potential new rule, but the district is nevertheless eager to share their hard work. According to Ratliff, these curricular materials will be made available on the Smithsonian Institute’s website in full, for any and all to download; the district has already heard from interested educators in Pennsylvania, Texas, and California, as well as several internationally. Once the materials are made available, “any teacher from anywhere in the world can download them and implement them in their classrooms.”

And perhaps these sorts of innovative approaches to learning will inspire the next generation of tinkerers and inventors to follow in Davenport’s footsteps—and into the patent office.