In September, a Japanese man was arrested for kicking an emotion-detecting robot named Pepper in a fit of drunken rage. The $1,600 humanoid robot survived the assault but was left with some damaged, slow-moving parts.

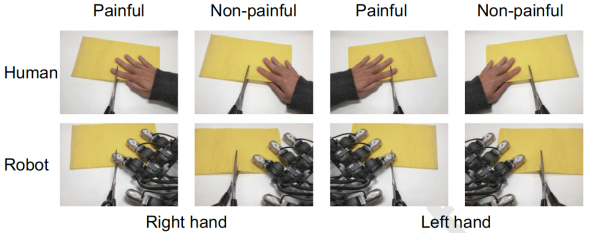

If thinking about this situation makes you feel bad for Pepper, you’re not alone. In a study published Tuesday in Scientific Reports, a team of researchers from Japan showed the first neurophysiological evidence that humans feel empathy for robots in pain. The team performed EEG (electroencephalography) brain scans on 15 adults who looked at pictures of human and robot hands in painful or nonpainful situations. Photos showed the hands being cut by a knife or a pair of scissors:

Screen grab from Scientific Reports

Along with measuring brain activity, the researchers also asked the participants how unpleasant they felt after observing the pictures and whether they thought the robot felt pain. While most people said the robot did not feel pain, their brain waves suggested otherwise.

The researchers tested for two modes of empathetic processing. “Top-down” processing is our cognitive ability to understand how others feel, while “bottom-up” is a more automatic, visceral response. “The ‘top-down process of empathy’ is the process that takes time for 350 milliseconds or more to recognize a situation and have it affect our cognition or consciousness,” co-author of the study Michiteru Kitazaki told Inverse. “Thus it is not contagious or automatic empathy.”

From the EEG results, the team found that humans’ bottom-up response was similar to both robot and human pain. However, their top-down empathy was weaker toward the robots. The researchers say this is because we have a harder time taking robots’ perspective, resulting in a slight “empathy gap.”

Part of the reason the people in the study felt empathy at all is because the robot hand looks like ours. We interpret the robot hand to be humanlike, triggering the same neural reaction as if it were a real hand. “Humans have a limited set of social and emotional responses, and we apply those processes to both human and nonhuman entities,” Doug Gillan, a psychologist who has studied human-robot interaction, told me. And the more human-ike those entities are—whether it’s a physical machine or a cartoon character like WALL-E—the stronger the empathy.

We could be decades away from creating a truly emotionally intelligent robot, and Sherry Turkle wants it to stay that way. Turkle, a professor of the social studies of science and technology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has spent over three decades studying human-robot interaction, rejects the notion that robots could even come close to replacing human-to-human bonds.

To her, creating an experiment that represents robots in pain is a “sad and dangerous enterprise,” she told me by email. “It increases our vulnerability to see them as having the arc of a human life, the experience of a human body.” She added, “We cannot learn empathy and caring from an object that has none to give.”