Like film sequels that fail to live up to the original, our ideas about the future almost inevitably disappoint. Much as we struggle to predict the ways we’ll be and what we’ll become, our suppositions about tomorrow tend to look ridiculous by the time that tomorrow arrives. This has rarely been clearer than it is with the arrival of Oct. 21, 2015, the date Doc Brown and Marty McFly leapt to in Back to the Future Part II. The movie’s message is that the future should remain unpredictable, yet many of its viewers have mocked the failure of its predictions.

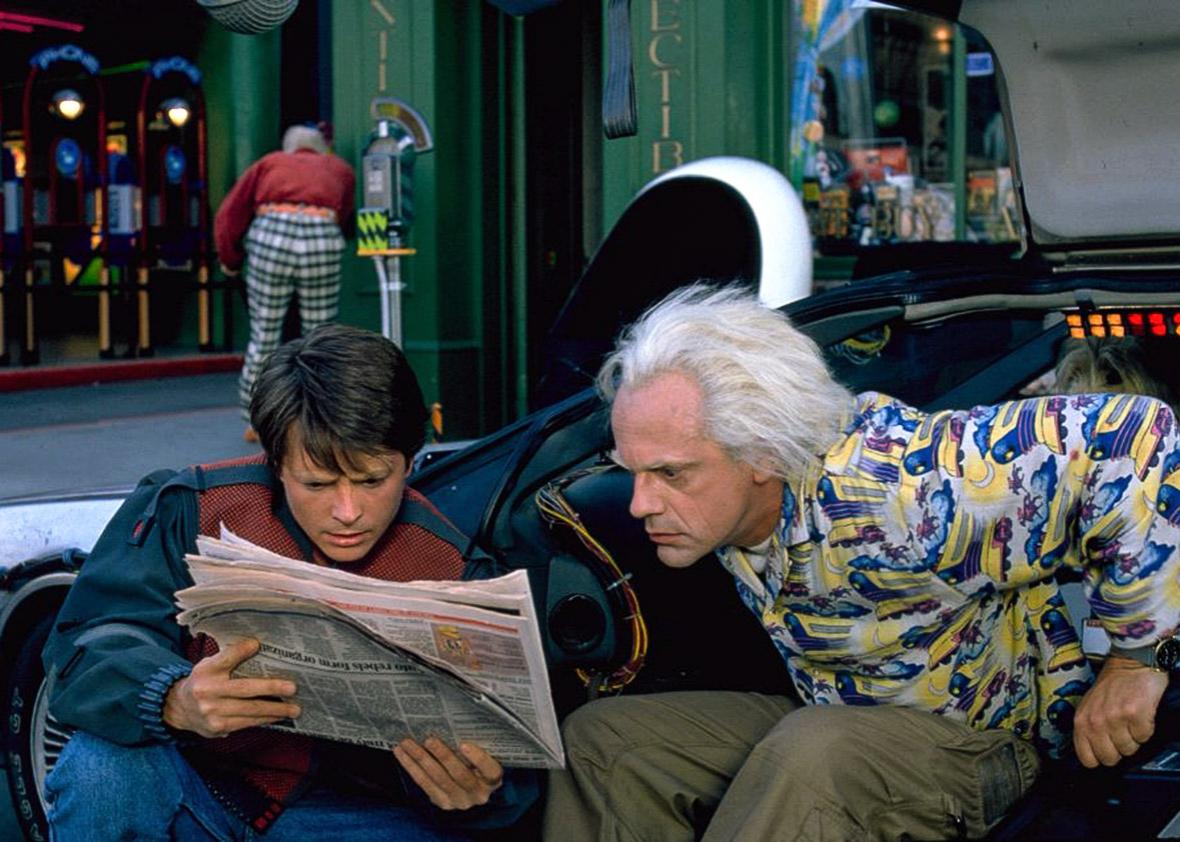

For every article celebrating the film’s legacy, there’s another comparing its 2015 to ours. Some critics, like CNN’s David Wheeler, drill down into its supposed mistakes, relentlessly cataloging the things it got wrong—like dehydrated pizza. Others take a more measured approach, acknowledging that it wasn’t entirely off base. And while almost everyone nods to the real world arrival of hoverboards, most are forced to admit that they only vaguely resemble those in the film. Even Christopher Lloyd and Michael J. Fox got in on the game, chatting about the movie’s relative absurdities for a Toyota ad.

Rewatching the film, it’s easy to see why such investigations appeal. Though its version of the future is comical and cartoonish, it also has a crystalline precision. The filmmakers commit so fully that their world feels real, even when its proposals are so deliberately absurd (for example, the long-suffering Chicago Cubs winning the World Series) that they’re obviously meant as jokes.

The pleasure of picking on Back to the Future II also comes from the exactitude of the date itself, a point in time so specific that it seems grounded and real. The dates in other science fiction films come and go—they’re typically just years, and to that extent they tend to feel arbitrary. Blade Runner takes place in 2019, but it might as well be 3019. Back to the Future II’s date, by contrast, isn’t just precise (despite the many hoaxes that have circulated around it in the past); it’s also essential to the plot of the film. Repeatedly visible on the dashboard of Doc Brown’s time machine, it’s a veritable character in its own right, sometimes seeming more real than the cartoonishly rendered Griff Tannen and Marty McFly Jr. Surely that’s why the actual arrival of the day this week makes it so easy to roll our eyes.

Here’s the trouble: When we obsess over what the movie did and didn’t get right, we may be missing its very essence. If Back to the Future II has a thesis, it’s that nothing is more dangerous than knowing your future—and nothing less productive than worrying over the way things might be. It’s a point that Christopher Lloyd’s wild-eyed Doc Brown makes over and over again. “No one should know too much about their future,” he tells Marty early on, only to repeat it almost verbatim mere minutes later. And he’s not wrong. As the story unfolds, Biff’s familiarity with things to come—in the form of a simultaneously comprehensive and slim sports almanac—all but destroys his timeline, turning once sunny Hill Valley into a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

In this light, perhaps we should be grateful that Back to the Future II’s future is so distant from our own present. This is a series in which the greatest danger is that we might turn out the way everyone expects us to—that we might become, in other words, the losers who our parents once were. If Marty McFly is a hero, it’s because he learns to swerve off course, heading in unexpected directions and exploring improbable avenues. Getting the future wrong actually squares with this story. Indeed, it may be just as essential to the film’s charms as Fox himself.

As I’ve argued before, science fiction’s power derives in large part from its capacity for alienation—its ability to discomfit and upset. We do the genre a disservice when we act as if its primary function is predictive. Though it’s always impressive when a writer can accurately extrapolate possible scenarios from current realities, their ability to do so is little more than a parlor game. The truly gifted are the ones who allow their audiences to see differently, encouraging them to imagine unlikely futures, regardless of when they’re from.

That’s a lot to ask from a film as goofy as Back to the Future II, of course. Still, it’s possible that it continues to entertain precisely because its future is so off base. Back to the Future II sees the world otherwise. And that’s a good thing.