If you back up your DVDs, or analyze your software to make sure it is secure, you may soon face a surprising penalty: the physical destruction of your computer, phone, or other device.

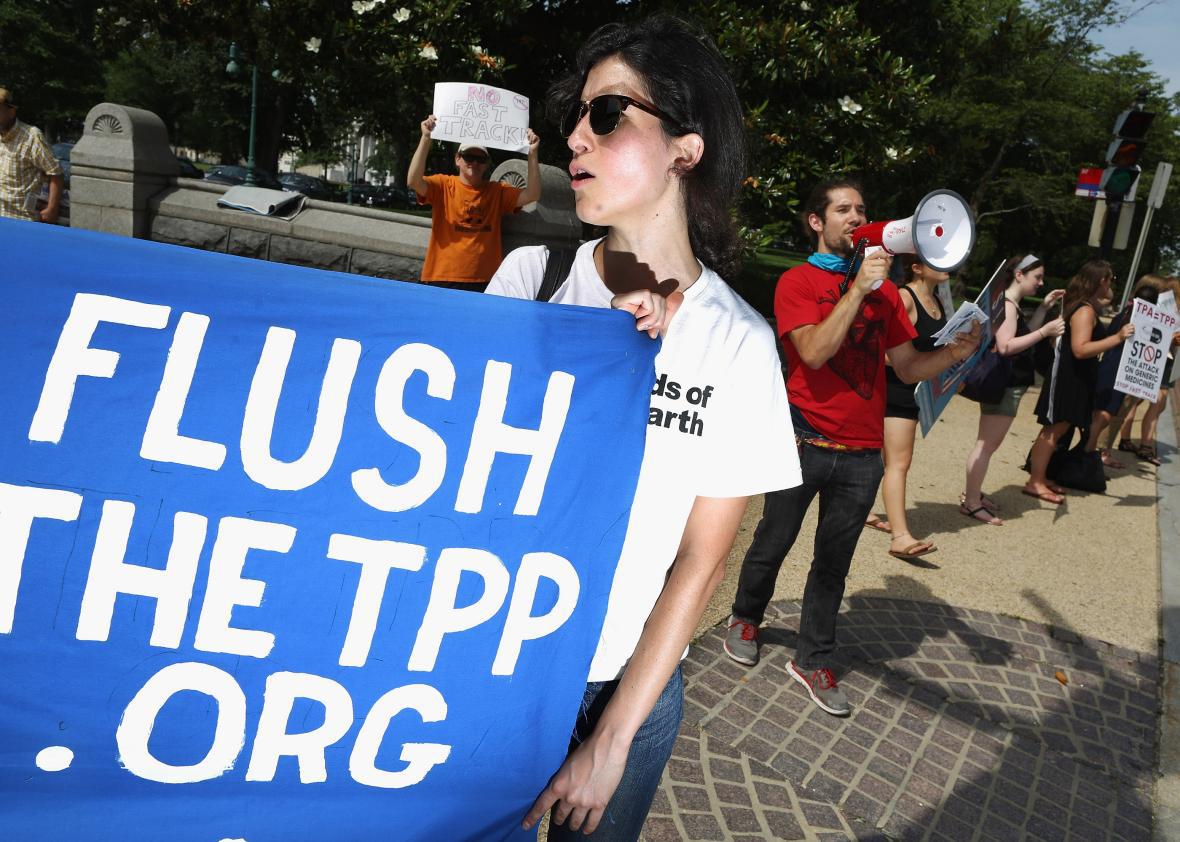

Hyperbole? Not so much, based on the latest leak from a budding international “trade” deal largely concocted and managed by the Obama administration. The Trans Pacific Partnership agreement, involving a collection of Pacific Rim nations, has been finalized and will soon go to Congress (and legislatures in some other nations) for approval. Based on what we know so far about a deal that has been kept secret from the American public, it is little more than a daisy chain of corporate favors in the guise of removing trade barriers.

Thanks to WikiLeaks, however, we know a great deal about one chapter in what promises to be a massive document. That chapter governs intellectual property—and the news is very, very bad for just about everyone but the corporate interests, led by the entertainment and pharmaceutical industries, that wrote most of the document. Indeed, the chapter is a wish list for cartels and control freaks.

And as Motherboard’s Jordan Pearson reported last week, there’s some extraordinarily nasty language relating to our ability to look into and modify the software code that increasingly governs how pretty much everything operates in the digital age. Bottom line for this provision: People who tinker in any way that interferes with controls designed to prevent tinkering could have their devices destroyed.

While the TPP permits nations to create exemptions for security, it requires the enactment of laws creating judicial power to “order the destruction of devices and products found to be involved” in that interference. But corporations have actively opposed all such exemptions in forums such as the U.S. Copyright Office’s triennial exemption exercise. That’s alarming, given that, as BoingBoing’s Cory Doctorow points out, security researchers have found massive holes in “vehicles, surveillance devices, voting machines, medical implants, and many other devices in our world.”

Maybe this is too alarmist. Surely our government isn’t insane enough to thwart research designed to keep us safer in the emerging “Internet of Things.” Yet tell that, for starters, to the automobile industry, where one of the world’s largest car makers, Volkswagen, cheated on emissions testing by tweaking its software. This crime against humanity—not an exaggeration, given the massive contribution this may have made to accelerating climate change—was discovered by researchers who, by good luck, discovered that VW’s cars had been spewing vastly more pollutants than the company claimed for years. This almost certainly would have been uncovered much earlier had the industry not relied on the Digital Millennium Copyright Act to “protect” its software from analysis; the DMCA made it illegal to circumvent “digital restrictions management.” Yet the automakers continue to adamantly oppose any exception to the DMCA.

This TPP provision, assuming it’s in the final document—won’t it be great when our government allows us to actually see it?—is just one of the many, many terrible “intellectual property” arrangements aimed at giving corporations greater control over their customers. When software is part of a product, as it is in so many things today and almost everything tomorrow, the very concept of ownership becomes an abstraction for the alleged buyer. And when we risk harsh penalties for even attempting to repair a device that’s defective, whether that’s because of the seller’s incompetence or venality, we are in a totally untenable, and frighteningly insecure, position.

We need to be going in precisely the opposite direction, and a too-little-noticed proposal this week shows how it might be done. A group of security experts looked into the absolutely horrifying, and willful, lack of security in devices most of us use every day—especially the Wi-Fi routers that let us share one Internet connection among a variety of devices—and asked the Federal Communications Commission to intervene.

In a letter to the FCC and a press release explaining their goals, more than 250 people, including Vint Cerf, one of the Internet’s creators, implored the agency to make these crucial devices more secure by forcing manufacturers to be more open about how they work. Among other things, the security experts asked the FCC to require that device makers a) provide public access to “source code”—the programming instructions that operate the device—so that it can be analyzed; b) provide ongoing security updates in timely ways; and c) be prevented from selling devices that don’t comply with those and other rules designed to ensure security.

The FCC should make this happen yesterday. Then, regulators and Congress should extend the compelling logic of this proposal to other devices—notably cars and mobile phones—that are notoriously riddled with flaws.

Meanwhile, it’s vital that Congress not agree to the TPP as it’s currently written. Thankfully, the deal is in trouble. Let’s hope the odd-couple combination of a corporate-dominated Obama administration and a Republican-controlled Congress doesn’t override common sense and the public good.