Instagram has decreed an end to the tyranny of the square, a longstanding policy that restricted users to posting photos with sides of even length. The company announced the end of its reign with some wistfulness. “Square always has been and will be part of who we are,” it tweeted. And yet freedom marches on, toward the manifest destiny of portrait and landscape formats.

To what end? The landscape format will be more accommodating to certain Instagram genres, like photos of friends posing arm-in-arm, against the backdrop of some fun locale. But at a time when technology has freed us from almost all boundaries of what content we can record and publish and when, there is something to be said for restrictions. Twitter’s 140-character limit is one example. Vine’s six-second rule is another. Like Haiku or iambic pentameter, these limitations create economies that force authors to consider what each word or image is worth.

If you’re making art, restrictions can be helpful. Brian Eno, the British music producer and artist, uses them to fight the chaos of choice. “In modern recording one of the biggest problems is that you’re in a world of endless possibilities,” he told the Telegraph in 2009. “So I try to close down possibilities early on. I limit choices. I confine people to a small area of maneuver.”

The square confines Instagram users to a small area of maneuver. It forces us to consider what details are essential, and which can be cropped out. It spares us from indulgence of the landscape and the false promise of the panorama.

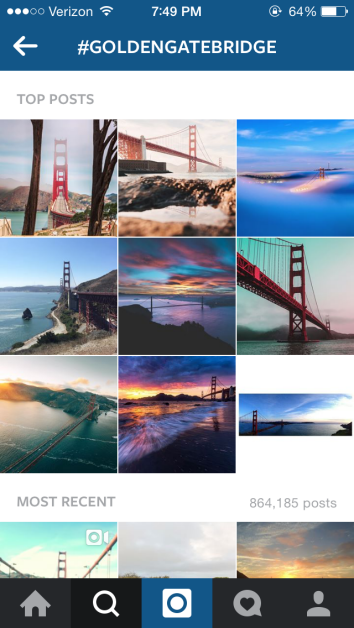

But Instagram, which is owned by Facebook, is in the business of accommodating its users, not challenging them. One of the problems with the square, the company explained in its announcement, is that “you can’t capture the Golden Gate Bridge from end to end.” This example speaks to the needs of a certain kind of Instagram user who enjoys planting his flag on settled territory. Like an iPhone videographer at a Taylor Swift concert, the guy Instagramming the Golden Gate Bridge is not creating a rare or essential document, only proof that he saw it with his own eyes.

And why did he bother doing that, anyway? Clearly, because photographs cannot really capture the scope of the Golden Gate Bridge, or St. Peter’s Basilica, or the view from your car window as you drive up the Pacific Coast Highway. The impulse to capture these moments on camera is shaded by the knowledge that the moment, in all its immediacy, is too large to fit in a frame of any size.

This is not to discount the medium altogether. Instagram photos, like memoirs, give us a good way to preserve and share moments from our lives. They allow us to retouch and stylize those moments to reflect how they felt, or how we want them to feel in retrospect. A couple of new framing options will not fundamentally change that.

Still, photos are not moments, and the square, in its inadequacy, forces us to acknowledge the distinction. It helps remind us that the feeling of standing at a vista with the breeze in your face and salt on your tongue and looking out at orange steel draped over nearly two miles of causeway cannot be boxed and shipped. Broadening the lens only adds dimensions to an illusion.