It only took a couple of days for the paranoia to get me. “I’m a little nervous because my phone’s data connectivity is acting weird,” I told my editor on our burner email addresses. “I can’t tell if it’s bad service in the conference center or something bad.” I had only been at the Black Hat cybersecurity conference in Las Vegas for a couple of days, but I was already losing it.

By the time I arrived at Defcon—Black Hat’s less mainstream sister conference, attended by die-hard hackers—I was keeping my devices completely off. The two conferences are known for being digitally dangerous. After all, the attendees are all cybersecurity professionals who thrive on the intellectual challenge of hacking. I had taken all of the usual precautions like withdrawing cash before I got to Vegas (so I wouldn’t fall prey to compromised ATMs or credit card skimmers), avoiding Wi-Fi, and bringing a laptop that didn’t have any personal data on it. I even remembered to put a Ninja Turtles band-aid over the webcam.

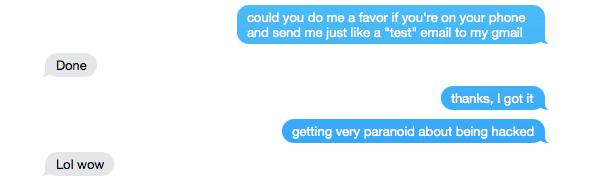

But I didn’t take maximum precautions, and that’s what started to drive me crazy. I brought my own smartphone instead of a burner, and though I kept it on airplane mode most of the time, I turned it on occasionally to text or use it as a mobile hotspot for my laptop. I always kept Wi-Fi and Bluetooth off, but there was that one time where I turned them both on for a second by accident.

Screencap from iMessage

It didn’t help—though it was pretty fascinating—when I toured the Network Operations Center at Black Hat and heard the admins talk about the treacherous malware they’d detected on the network and the new attacks they’d encountered for the first time. It was a dark room crammed with computers and big screens showing real-time network updates and threat tracking. “We say that there are a lot of security professionals here, but that’s just corporate speak for hackers,” said NOC operations leader Neil Wyler (also known as Grifter). “They take a look at all these new techniques and stuff and they immediately try them on each other other. The Black Hat network is one of the, if not the, most hostile networks I’ve ever seen.”

Though Black Hat and Defcon draw huge crowds, they still coexist among the gamblers and vacationers in Las Vegas. And as I walked around, I saw everything that was happening through the lens of my paranoia. What about the people on the Starbucks line who weren’t hackers? I could tell they didn’t know what was lurking in the casino, because they were checking their bank apps and swiping their credit cards with abandon. Lucy Teitler also thought about this after attending Defcon last year. In a Motherboard piece she described an internal battle about whether she should warn people. A security vendor she talked to about bystanders described them as “collateral damage.” But she couldn’t bring herself to intervene. “Why ruin their fun? Why tamper with their pleasant ignorance?”

Now that I’ve left the belly of the beast and feel a little freer to check my email, it’s tempting to let my fear fall away. I don’t want to live in the state of intense vigilance that I reached at the conferences. But knowing what that feels like seems pretty valuable, because it will stay in the back of my mind and motivate me to make small changes. My descent into paranoia may not be enough to motivate you to do the same, but I hope it helps. Because the stakes are even higher outside of Vegas.