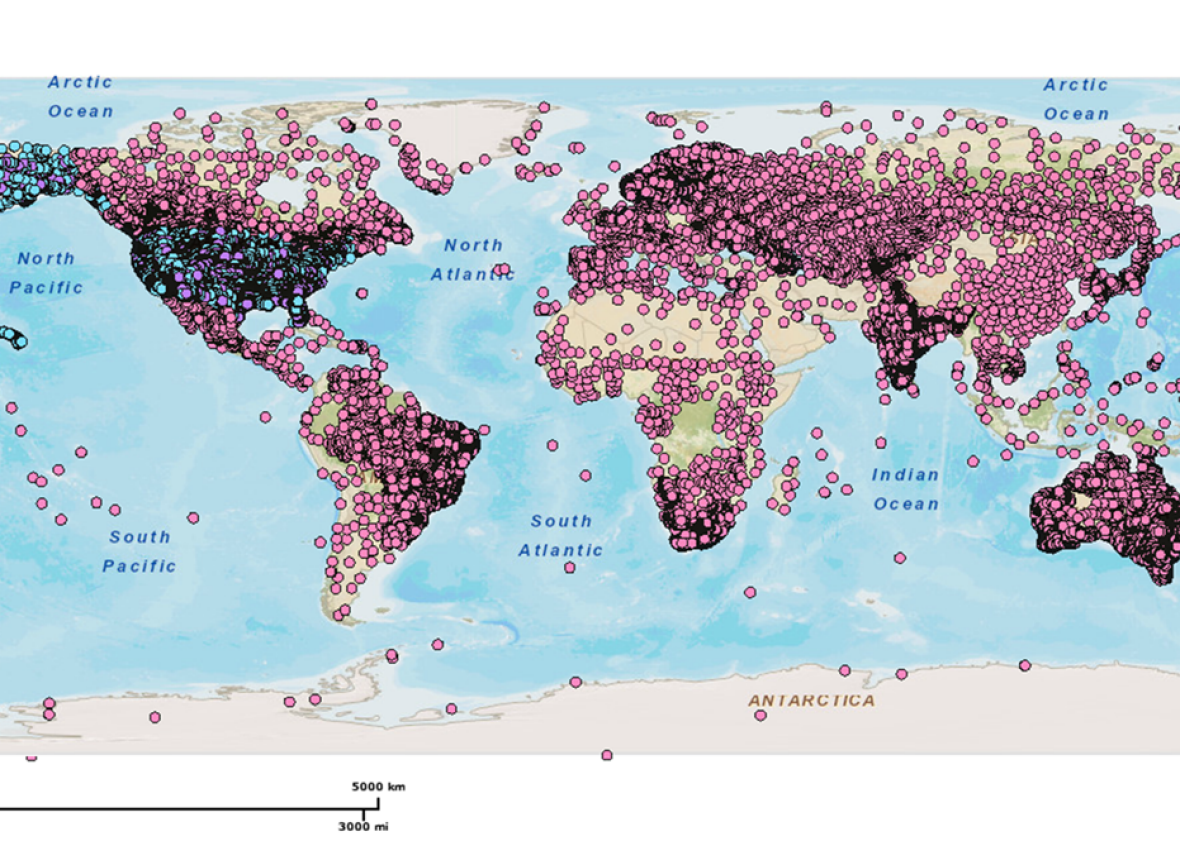

Zambia is roughly the size of Texas. While Texas currently has thousands of automated weather stations feeding data continuously into global weather models, Zambia has just 36.

That’s a huge problem, not only for accuracy of global weather forecasts—in which more reliable information from data-sparse regions like Africa really matters—but more importantly for farmers and other people dependent on rainfall for their livelihoods. In places like Zambia, better weather forecasts could be a game changer.

Enter 3-D printing. A new initiative aims to use 3-D printers, beginning in Zambia, to develop a network of functional weather stations for meteorologists there. Automated weather stations are a critical component of weather forecasting, taking measurements of temperature, humidity, wind, and air pressure on a regular basis. That information, along with data from satellites and other observing networks, forms the basis of modern weather forecasting. If you don’t know what the weather is doing right now, there’s no hope of anticipating the future.

Martin Steinson, a scientist with the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, is working with the U.S. National Weather Service using a grant from the U.S. Agency for International Development to design the 3-D–printed parts that will make up the weather stations.

Steinson was recruited into this project by his colleague Kelly Sponberg, who noticed that commercial weather stations were especially ill-suited to rural regions of Uganda. Parts broke, and the designs quickly became obsolete. His idea: Design an open-source, low-power automated weather station that could be manufactured in Africa.

At first, Steinson was skeptical of the idea that 3-D–printed weather stations were a viable alternative. “I thought he was pulling my leg,” Steinson told Slate.

Three years later, Steinson has lowered the total cost of his 3-D–printed automatic weather station to about $200, compared with about $15,000 for similar commercial models. He’s planning to travel to Zambia later this month, where he will help the Zambia Meteorological Department install a few stations for field-testing purposes. Within a year, he expects the stations to be in production in Zambia.

In addition to the 3-D–printed weather stations, which will be deployed via a partnership with community radio stations, Steinson is also discussing options for a companion weather forecast model that can be installed and run essentially on a laptop—a huge leap forward from the supercomputing requirements. Steinson’s colleagues have already developed a prototype weather model along with the Ghana Meteorological Agency.