While the process that generates lightning is fairly well-understood, it’s still not totally clear what parts of the lightning bolt are responsible for thunder. A recent study predicted that lightning strikes could increase by up to 50 percent in the United States by the end of the century as rainstorms become more intense due to global warming. So lightning is a hot scientific topic right now. (Pardon the pun.)

We do know what thunder is: It’s the sound created by the shock wave that’s quickly generated by lightning’s intense heat. The air very near the lightning strike quickly expands, and the intensity of the resulting boom obviously changes based on how far away you are from it. At extremely close range, the acoustic energy from thunder itself is strong enough to cause injury and property damage.

Last summer, to study the acoustic energy that thunder creates, researchers strapped a Kevlar-coated copper wire to a rocket and launched it during the middle of a thunderstorm on a military base near Gainesville, Florida, hoping to tap into the cloud’s electricity source. They didn’t have to wait long:

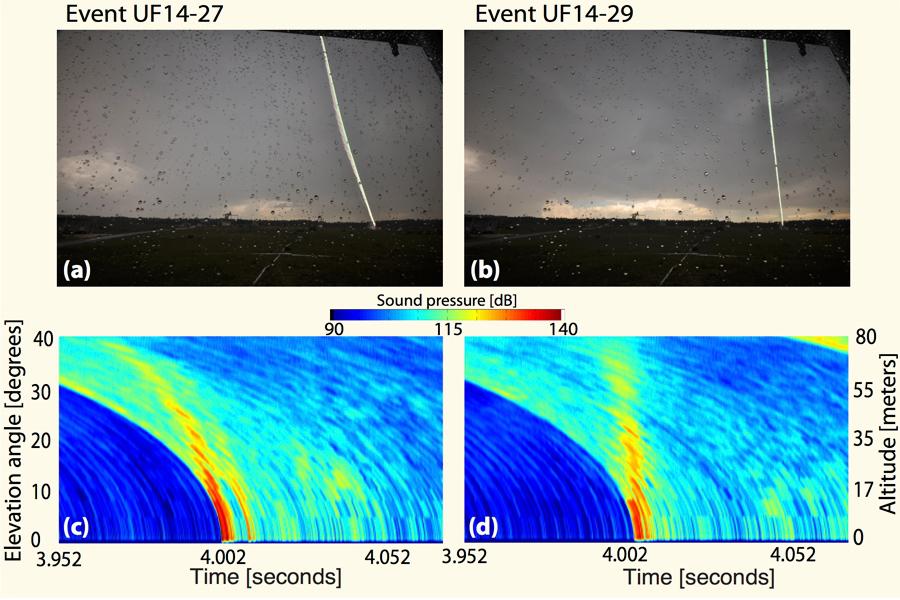

“At first I thought the experiment didn’t work,” said Maher Dayeh, the study’s lead author, in a press statement. “The initial constructed images looked like a colorful piece of modern art that you could hang over your fireplace. But you couldn’t see the detailed sound signature of lightning in the acoustic data.”

To image the thunder, Dayeh strategically placed 15 highly sensitive microphones about 300 feet away from the rocket’s launch pad. Data from the array were able to triangulate the source of the most intense sound and its associated frequencies. Turns out, the loudest part of thunder actually originates very close to the Earth’s surface, not in the cloud. “That’s where the lightning channel is attaching into the ground,” Dayeh said.

UF/FIT/SRI

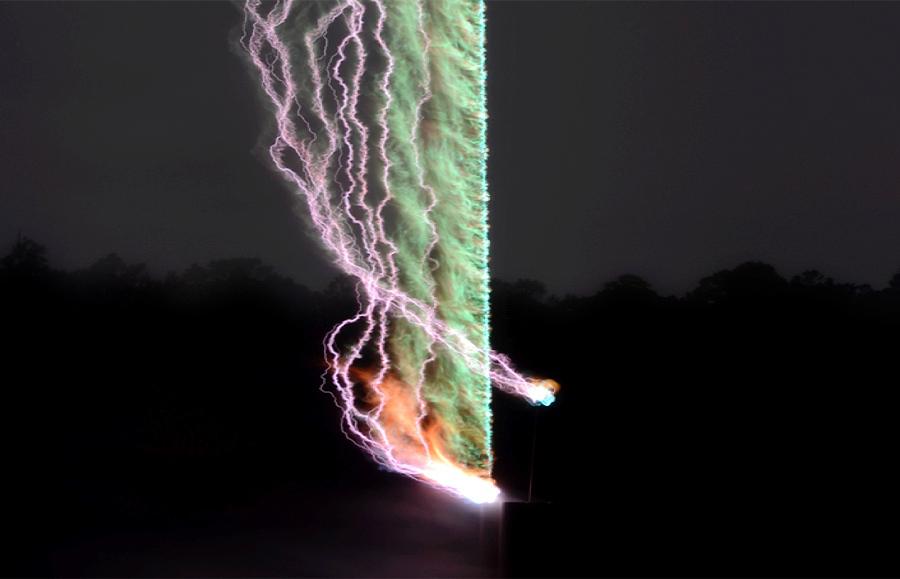

The greenish glow in the long-exposure photograph at the top of this post is due to the initial artificial strike along the copper wire. The purple are the much more brilliant return strokes. The return strokes—the most visible part of lightning to the naked eye—actually travel from the ground upward, but our eyes are too slow to notice. The associated images of the thunder with this lightning strike show nine return strokes.

These results were presented Wednesday at a joint meeting of American and Canadian geophysical societies in Montreal. Dayeh hopes his team’s work will be compared with future similar studies of natural, more jagged lightning.