Stem cell research and three-parent babies have been in the news lately for pushing bioethical boundaries, but at the frontiers of science there are always new quandries. The latest comes from Chinese researchers who say they have edited specific genes in human embryos. The work is, ahem, controversial, to say the least.

Rumors about the Sun Yat-sen University work circulated for weeks before Nature News confirmed them last week. (The relevant study was published April 18 in the journal Protein & Cell.) The researchers used nonviable embryos from fertility clinics to test a gene-editing method called CRISPR/Cas9 that is already widely used to create genetically altered organisms like yeast, zebra fish, and mice for scientific and medical testing. The Chinese researchers were attempting this DNA engineering to see if they could target a gene that can cause a serious blood disorder called β-thalassaemia.

“I suspect this week will go down as a pivotal moment in the history of medicine,” the influential science journalist Carl Zimmer wrote on his National Geographic blog after the research’s existence was confirmed. But the rumors alone prompted sides to form for the debate. A group of scientists, including some who worked to develop CRISPR and other genetic engineering tools, wrote in Science, “At present, the potential safety and efficacy issues arising from the use of this technology must be thoroughly investigated and understood before any attempts at human engineering are sanctioned, if ever, for clinical testing.”

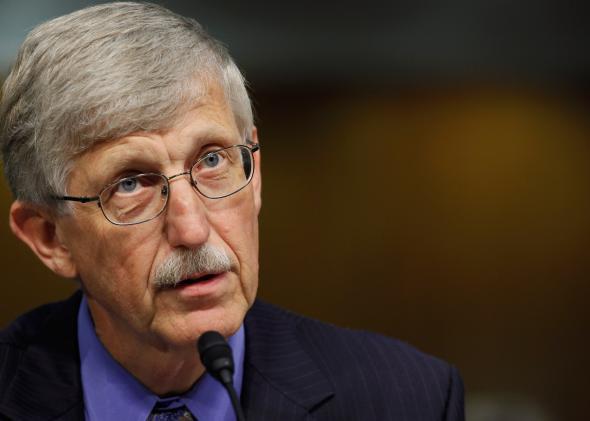

On Wednesday, the National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins wrote in a statement that he agreed:

Research using genomic editing technologies can and are being funded by NIH. However, NIH will not fund any use of gene-editing technologies in human embryos. The concept of altering the human germline in embryos for clinical purposes … has been viewed almost universally as a line that should not be crossed.

Collins said the agency has ethical concerns about funding genetic alterations that could be passed to future generations of people who can’t consent to being born with modified DNA. He also cited NIH and FDA guidelines and legislation like the 1996 Dickey-Wicker amendment (which forbids government funding for research that destroys human embryos or creates them soley for science) as reasons that the NIH is banning genetic engineering of human embryos.

Some researchers are already pushing back against the supposed consensus the NIH references. “I am not in favor of the NIH policy and I believe that the Chinese paper shows a responsible way to move forward,” David Baltimore, a biologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, told Nature News.

Dieter Egli, a researcher at the New York Stem Cell Foundation, told MIT Tech Review last week, “These authors did a very good job pointing out the challenges. … They say themselves this type of technology is not ready for any kind of application.”

Maybe they can move ahead in China, but in the U.S., gene-editing in human embryos won’t be funded any time soon.