The pro-ISIS Twitter ecosystem remains large, vibrant, and dangerous, according to a new survey published by the Brookings Institution, but efforts to suspend supporters’ accounts are disrupting the group’s ability to get its message out.

The report, by terrorism analyst J.M. Berger and Jonathon Morgan, a developer for the nonprofit crowdsourcing firm Ushahidi, estimates that there were roughly 46,000 pro-ISIS Twitter accounts between September and December 2014, though not all of them were active at the same time.

About 73 percent of those tweeted in Arabic, 18 percent in English, and 6 percent in French, a breakdown that roughly corresponds to what we know of the demographic composition of ISIS itself.

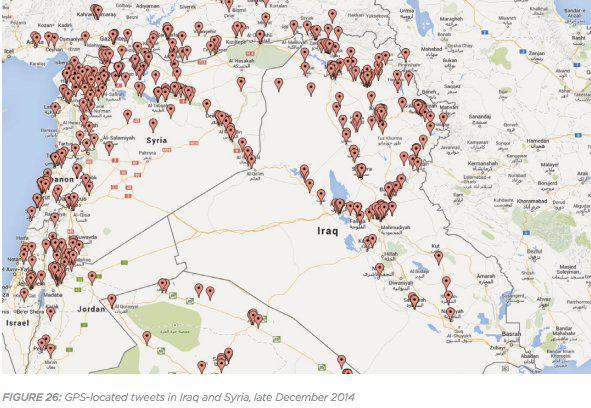

Not surprisingly, the vast majority of pro-ISIS tweeters don’t have geolocation turned on for their tweets—the organization has threatened to confiscate the phones of those who do—but of the small minority who did, 28 percent were in Iraq and Syria, 27 percent in Saudi Arabia, and just a scattered handful in other countries. There were just a few in Europe and none in the United States, which makes sense given how quickly posting pro-ISIS propaganda online can lead to a knock on your door in those countries. Here’s a map of the GPS-located tweets sent out from the Middle East in late December 2014:

Courtesy of Brookings Institution

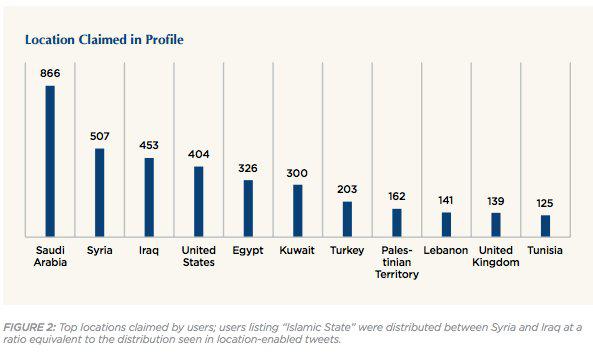

However, there was more variety among the users who posted (unverifiable) location data in the profiles:

Courtesy of Brookings Institution

ISIS-supporting accounts had an average of 1,004 followers, which is much higher than the average Twitter user. Only around 4 percent have more than 5,000 followers. Accounts like that of Shami Witness, the influential propagandist with 17,700 followers who was recently revealed to be a Bangalore corporate executive, are the exception. ISIS tweeters are also more active than average with about 7.3 tweets per day, but much of the group’s activity is driven by a small group of superusers with hundreds of tweets per day.

About 69 percent of ISIS supporters with smartphones are running Android compared with 30 percent with iPhones, a factoid unlikely to turn up in Google’s marketing material.

Twitter began shutting down ISIS accounts in the summer of 2014 and stepped up its suspension campaign against the group last fall, during the period that Berger and Morgan were studying. About 1,000 of the accounts under observation got shut down. ISIS’s “official” accounts have been more or less eliminated, though the group still finds ways to get the word out.

Suspending terrorist accounts is controversial. Some argue that it’s a pointless game of whack-a-mole, with offenders just reregistering under different aliases, and counterproductive, since social media can provide valuable information to intelligence agencies in law enforcement. Berger and Morgan reject the first complaint, finding that while it will probably never be possible to eliminate ISIS from Twitter entirely, there’s clear evidence that the group’s efforts have been disrupted by the suspensions. Last summer, experts were stunned by ISIS’s Twitter savvy, including its ability to launch coordinated hashtag campaigns—and even hijack the publicity surrounding events like the World Cup—to circulate propaganda. At one point, ISIS was even releasing its own tailored social media apps.

After the suspension campaign, fewer accounts were being created, activity was down, and users were spending more of their time tweeting at one another in an effort to rebuild their networks rather than spreading propaganda, recruiting new members, or harassing opponents. For potential ISIS recruits or “lone wolves” looking for inspiration, pro-ISIS material is harder to find than it was a few months ago. (Perhaps the best evidence that account closures have frustrated ISIS: Members of the group have threatened Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey.)

Berger and Morgan agree that that Twitter is a valuable source of intelligence on ISIS, but nonetheless feel that a large number of accounts could still be eliminated without much negative impact.

They do, however, suggest a different unintended consequence of account suspensions. The crackdown has made ISIS’s Twitter network more internally focused, with users more likely to only follow one another’s accounts. This means users are also less exposed to outside, potentially deradicalizing influences. By attempting to stamp out ISIS’s Twitter ecosystem, Twitter may have turned it into even more of an echo chamber.

One topic that the report doesn’t address is whether ISIS’s reliance on decentralized social media users to spread propaganda affects its ability to control the message received by its global followers. ISIS, the Kouachi brothers, who attacked Charlie Hebdo last summer, were al-Qaida supporters. But Amedy Coulibaly, who attacked a Kosher supermarket on their behalf, declared his allegiance to ISIS. While the two groups are formally at war in Syria, their international followers are willing to work together.

It will be interesting to see if, by allowing its followers, many of them thousands of miles from the battlefield, to spread its message, ISIS also ends up allowing them to shape it.