By now, it’s pretty clear that we’re starting to see visible manifestations of climate change beyond far-off melting ice sheets. One of the most terrifying implications is the increasingly real threat of wars sparked in part by global warming. New evidence says that Syria may be one of the first such conflicts.

We know the basic story in Syria by now: From 2006-2010, an unprecedented drought forced the country from a groundwater-intensive breadbasket of the region to a net food importer. Farmers abandoned their homes—school enrollment in some areas plummeted 80 percent—and flooded Syria’s cities, which were already struggling to sustain an influx of more than 1 million refugees from the conflict in neighboring Iraq. The Syrian government largely ignored these warning signs, helping sow discontent that ultimately spawned violent protests. The link from drought to war was prominently featured in a Showtime documentary last year. A preventable drought-triggered humanitarian crisis sparked the 2011 civil war, and eventually, ISIS.

A new study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science provides the clearest evidence yet that human-induced global warming made that drought more likely. The study is the first to examine the drought-to-war narrative in quantitative detail in any country, ultimately linking it to climate change.

“It’s a pretty convincing climate fingerprint,” said Retired Navy Rear Adm. David Titley, a meteorologist who’s now a professor at Penn State University. After decades of poor water policy, “there was no resilience left in the system.” Titley says, given that context, that the record-setting drought caused Syria to “break catastrophically.”

“It’s not to say you could predict ISIS out of that, but you just set everything up for something really bad to happen,” Titley told me in a phone interview. Given the new results, Titley says, “you can draw a very credible climate connection to this disaster we call ISIS right now.”

The study’s authors are clear that global warming did not directly cause Syria’s civil war—it took a mix of underlying social vulnerability and an antagonistic government to do that. But it does provide compelling evidence that, when combined with the effects of increased population pressure and the poor policies of the Assad regime, the drought made a bad situation worse.

Titley says that the connection between climate change and the Syrian conflict means it could be “a harbinger of where we may end up more in the future.” He has helped shape the U.S. military position on climate change to a more proactive one, casting climate change as a “threat multiplier” for national security. My interview with him last year remains one of the most fascinating and terrifying conversations I’ve ever had.

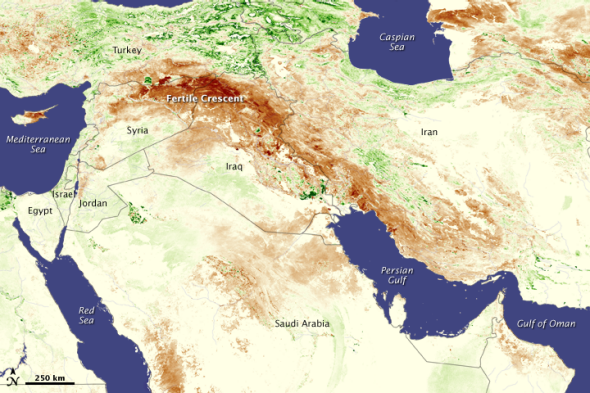

Image: NASA

The consistency of climate models made the eastern Mediterranean a great place to start looking for possible connections between human-cause climate change and conflict. The Middle East has already seen decades of drying, which is expected to intensify for the next 20 years and beyond as a result of climate change.

Colin Kelley, a climate scientist at the University of California–Santa Barbara and the study’s lead author, said long-term climate trends made Syria’s 2006-2010 drought two to three times more likely, and future trends point in the same direction.

Of course, since 2011, the Syrian conflict has ballooned into a multinational war, with nearly 4 million refugees across the region. Are they the world’s first climate change refugees due to conflict?

“Under international law, there’s no such thing as climate refugees,” said Marcus King, professor of international affairs at George Washington University and an expert in climate and security. “So far, the environment hasn’t been seen as an actor that’s able to persecute people.” But, he said, “I would certainly call them climate migrants. … There are other factors, but that’s the dominant factor.”

Severe drought resumed in late 2013, and ISIS has used the resulting water shortfall to its advantage. King says at one point last year, ISIS controlled all three major dams in Iraq, a feat that he says quickly motivated an enhanced U.S. military presence there.

Beyond the case of Syria, the new study provides a powerful tool for researchers interested in how human-induced climate change may be affecting conflict worldwide. King points specifically to Libya, Egypt, and Yemen as next potential fronts in climate change-fueled conflict. In general, climate change poses an increasing challenge for fragile states to provide stable services.

While violent conflict over water is far from likely in the United States, Kelley says “we need to be proactive.” Kelley says one of the biggest lessons that California can learn from Syria is: “Let’s not just assume that things will be fine.” Recent research showed that climate change will increase the risk of multidecadal “megadrought” in the West dramatically.

Titley likens the Syrian drought to “throwing a match into gasoline vapors.” In California, it’s more like “throwing match into diesel. It goes out.”

Until recently, climate and security experts have focused their research mostly on the humanitarian and disaster-relief implications of increasing extreme weather. “The Syrian conflict is one of the first instances of the dark side, the evil face of climate and security, not the last,” Titley said.

“I think, unfortunately, we will see more and more of these, and now the question is: Which one of these becomes the Titanic moment that grabs the world’s attention?”