This post originally appeared in WIRED.

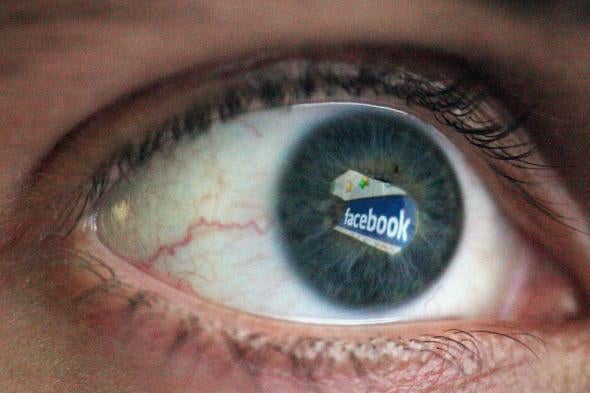

Jessie Lorenz can’t see Facebook. But it gives her a better way to see the world—and it gives the world a better way to see her.

Lorenz has been blind since birth, and in some ways, this limits how she interacts with the people around her. “A lot of people are afraid of the blind,” she explains. “When you meet them in person, there are barriers.” But in connecting with many of the same people on Facebook, she can push through these barriers. “Facebook lets me control the narrative and break down some of the stigma and show people who I am,” she says. “It can change hearts and minds. It can make people like me—who are scary—more real and more human.”

Lorenz uses Facebook through an iPhone and a tool called Voiceover, which converts text into spoken words. It’s not a perfect arrangement—Facebook photos are typically identified only with the word “photo”—but in letting her read and write on the social network, Voiceover and other tools provide a wonderfully immediate way to interact with people both near and far.

“I can ask other parents about a play date or a repair man or a babysitter, just like anyone else would,” says Lorenz, the executive director of the Independent Living Resource Center, a nonprofit that supports people with disabilities in the San Francisco Bay Area. “Blindness becomes irrelevant in situations like that.”

Lorenz is one of about 50,000 people who actively use Facebook through Apple Voiceover. No doubt, many more use it through additional text-to-speech tools. And tens of thousands of others—people who are deaf, or can’t use computer keyboards or mice or touch screens—use the social network in ways that most of its 1.3 billion users do not. They use closed captioning, mouth-controlled joysticks, and other tools—some built into Facebook, some that plug into Facebook from the outside.

So many people are using the social network through such tools, Facebook now employs a team of thinkers dedicated to ensuring they work as well as possible. “We wanted to build empathy into our engineering,” says Jeff Wieland, who helps oversee this effort.

He calls it the Facebook Accessibility team, and it’s a vital thing. Not all online services are well-suited to people with disabilities. “Google is really lousy,” says Lorenz, explaining that she can use Gmail but not Google Docs or Google Calendar. And as a service like Facebook evolves—with engineers changing things on an almost daily basis—they consistently run the risk of undermining Voiceover and other alternative means of using the social network.

Tech companies have long worked to ensure their software and services can be used by people with disabilities. Ramya Sethuraman, who helps drive Facebook’s effort, worked on similar issues with old-school software at IBM. But in the modern age, where so many services change from day to day, this requires a greater diligence.

As Sethuraman points out, other companies are tackling these issues in ways similar to Facebook, including Twitter, LinkedIn, and eBay, and for Lorenz, the improvement is apparent. “The industry is becoming more conscious about these things,” she says, “and very slowly, it’s getting better.”

The task is certainly more difficult in the modern age. But at the same time, the possibilities are greater. And the stakes are higher. “There are more people with disabilities than ever before. People are living longer. People are more likely to survive accidents,” says Adriana Mallozzi, who has cerebral palsy, typically uses Facebook and other services through a joystick she can control with her mouth, and serves as a kind of tech consultant for people with disabilities in the Boston area. “Companies have to take this into consideration.”

Jeff Wieland founded the Facebook Accessibility team in 2011. He’d come to the company as a part-timer a few years earlier, helping out with customer support to pay the bills while in medical school, and somewhere along the way, this morphed into a career serving Facebookers in other ways.

After dropping out of med school, he joined the company’s user experience research lab, where he explored how the world at large used Facebook, testing the classic “big blue app” in various ways, including through focus groups. And at one point, he realized that a portion of the app’s audience was underserved. “So, I pitched the accessibility idea,” he says. “Our goal as a company is to connect the world. If you really believe that, we need to include people with disabilities.”

He soon won approval for a dedicated accessibility team, and Sethuraman was his first hire. Basically, they work with other teams across the company to fine-tune the social network so it can be readily used by the blind, the deaf (videos have sound), and those who can’t use a keyboard or a computer mouse or a touch screen. “We think about how we can set up our engineers to build services that can be used with something like a screen reader,” Wieland says, referring to tools like Voiceover. “You have to build your code so it will work well with these things.”

Most notably, Wieland and Sethuraman work closely with Facebook’s product infrastructure team, the team that builds the basic components used by services across the social network—things like buttons and menus. “If other engineers use these tools,” he says, “they get a certain amount of accessibility for free—without even having to think about it.”

But Wieland and Sethuraman also directly target these other engineers—engineers across the company. Together with the company’s central quality-assurance team, they pinpoint holes in the Facebook interface and work with the appropriate engineers to fix them.

At one point, for instance, they helped develop a way of automatically providing Vocieover users with more information about the many photos uploaded to Facebook, so the blind can better understand what’s pictured—as opposed to merely reading what people are saying about the photos. Now, together with tools like Voiceover, Facebook can tell the blind when a photo was taken (based on meta-data uploaded with the photo) or who’s in it (based on tags from users). “We will try to pull in information,” Wieland says, “that tells a story.”

Recently, in a busy walkway at the heart of the company’s headquarters in Menlo Park, California, Wieland and Sethuraman installed something they call the Facebook Empathy Lab. It’s not for research and testing per se. It’s meant to give all Facebook employees an idea of what it’s like to use the social network through Voiceover or short keys or closed captioning or high-contrast interfaces.

It’s essentially a row of laptops and phones. With one device, you can only drive Facebook with your voice. With another, you can only use keyboard shortcuts—not mice. And a long row of phones show what it’s like to use Facebook in places where screens are small and network bandwidth is smaller.

The hope is that the company’s engineers will keep both physical disabilities and technical restrictions in mind when building something new—not just when Wieland pays them a visit, not just after it’s built. “We wanted to tie this basic thing to the Facebook culture. We wanted it to be like hacking,” Sethuraman says, referring to the continuously creative mindset that pervades the company.

All this may seem like an inexact science. But the results of the team’s work are apparent—at least to some. Eighteen months ago, Lorenz says, using Facebook was far more difficult—she couldn’t tag people and couldn’t upload photos, for instance—and the company’s software updates would often undermine her ability to use Voiceover.

Certainly, things are far from perfect on Facebook. When Mallozzi uses the social network on her phone—tapping into it via Bluetooth wireless controls built into her wheelchair—she wishes she could more easily scroll through the service and navigate individual pages. And despite recent changes made by Wieland and team, Lorenz says Facebook still doesn’t give her much info on photos. But that may change.

The company’s new artificial intelligence lab is exploring ways of using image recognition technology to generate captions that would identify photos in more precise ways—and actually describe what’s pictured. And as this is rolled out, you can bet that it will work with Voiceover too. As Wieland says: “We were just talking about this at lunch today.”

More from WIRED:

What Black Hole Winds Tell You about Galaxies

Hackers Cut in Line at the Burning Man Ticket Sale—And Get Caught

The Insanely Dangerous, Weirdly Meditative Sport of Freediving

Silicon Valley Could Learn a Lot From Skater Culture. Just Not How to Be a Meritocracy

How the NSA’s Firmware Hacking Works and Why It’s So Unsettling