One of the reasons the American judicial system is so obsessed with providing people due process before depriving them of liberty is that prison is really, really awful. American prisons don’t just limit your movement and actions; they also attempt to limit your speech, your writing—even your thoughts.

Given that sad reality, the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s new blockbuster report on Facebook censorship in the South Carolina prison system isn’t particularly surprising. Through a series of Freedom of Information Act requests, the EFF discovered that the South Carolina Department of Corrections made “Creating and/or Assisting With A Social Networking Site” a “Level 1 offense” in 2012. According to this rule, inmates commit a Level 1 violation every day that they access a social network—even if they do so indirectly, by, for instance, asking a family member to update their status. Under the new regime, prison officials have brought more than 400 disciplinary cases for using Facebook. Many of these inmates lose telephone and visitor privileges; some wind up in solitary confinement. One inmate received a sentence of 37 years in isolation for repeated Facebook usage.

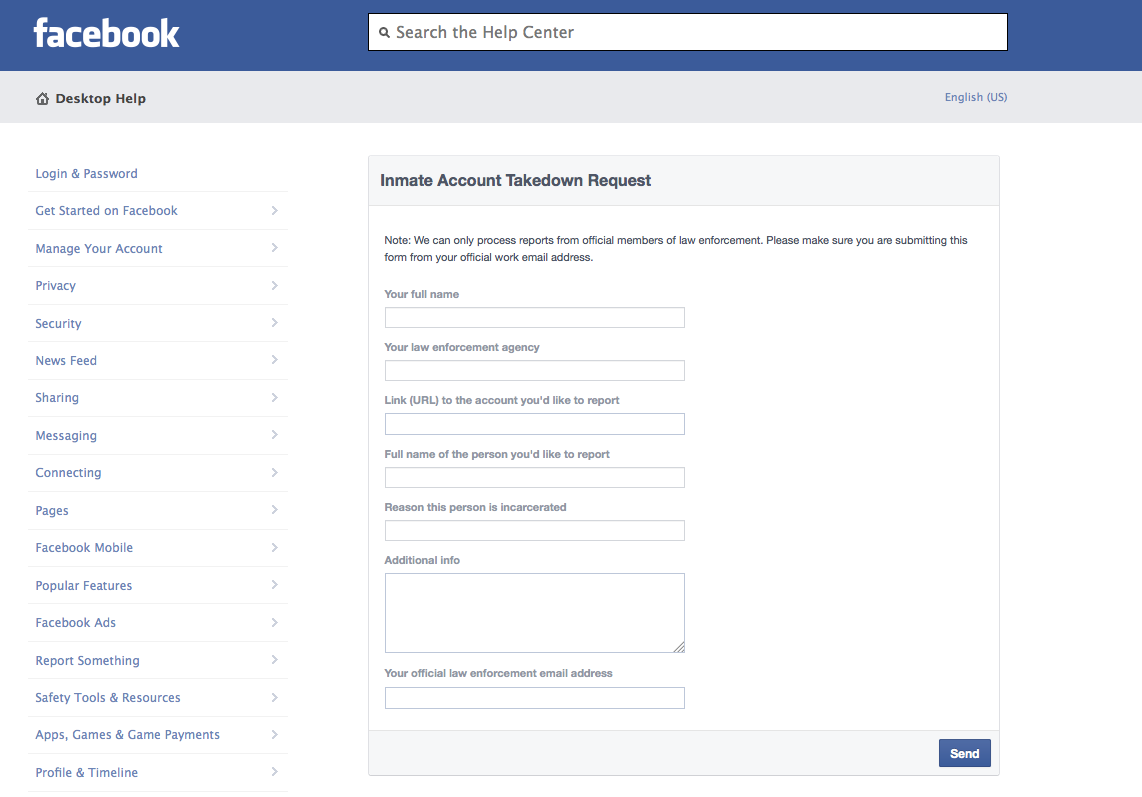

Facebook—a self-proclaimed champion of Internet freedom and privacy rights—has obediently facilitated South Carolina’s censorship regime. Once prison officials discover that an inmate has asked an acquaintance to update his Facebook status, they can simply fill out Facebook’s handy “Inmate Account Takedown Request” form. The company claims it doesn’t suspend prisoners’ Facebook pages for violating prison regulations, but rather for violating Facebook’s Terms of Service by giving their password to somebody else. But the EFF uncovered at least one instance in which Facebook suspended a prisoner’s account explicitly “for not following inmate regulations.”

What South Carolina is doing here is an egregious perversion of justice. Prisons frequently censor inmates’ communication under the pretext of maintaining safety and security, as Kevin Roose explained in his fantastic series on technology in prison. But it’s difficult to see how an inmate could threaten anybody’s safety by asking a relative to update his Facebook status. And even if that simple act of free expression did pose some tenuous risk to security, a sentence of years in solitary confinement is surely a wildly excessive punishment.

Unfortunately, the courts have given prisons exceedingly wide latitude to discipline their inmates however they see fit. So long as prison officials can toss out some pretense about a security needs, the courts will sign off on almost any censorship of speech. (Religious expression is a different matter.) Moreover, the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” forbids only “extreme sentences that are grossly disproportionate to the crime”—probably too high a standard to help these inmates. And even then, internal prison discipline is held to an especially lenient standard of constitutional review. In other words, South Carolina has close to free rein to punish its prisoners however it wants.

Does that mean inmates have absolutely no way to communicate with the outside world through social networks? Not quite. Civil liberties groups have already begun challenging laws and regulations somewhat similar to South Carolina’s by focusing on the third party—usually a friend or family member—who actually posts a status update to the inmate’s Facebook page. In a recent lawsuit, the American Civil Liberties Union argued that the First Amendment always prohibits the government from retaliating against people for exercising protected speech. Under this theory, prisons might unconstitutionally “chill” the expression of inmates’ relatives when prison officials punish inmates for passing along messages to be posted to Facebook.

Whether or not these theories hold water in court, there is one immediate solution at hand: Pressure Facebook to end its obsequious compliance with prison censorship. The very existence of an “Inmate Account Takedown Request” form is an affront to free expression, as is Facebook’s apparent willingness to suspend prisoners’ accounts on a technicality with no more evidence than a warden’s word. Facebook shouldn’t touch an inmate’s account absent compelling evidence that he is using it to threaten security. The punishments meted out in American prison are horrible enough without America’s largest social network colluding in the cruelty.