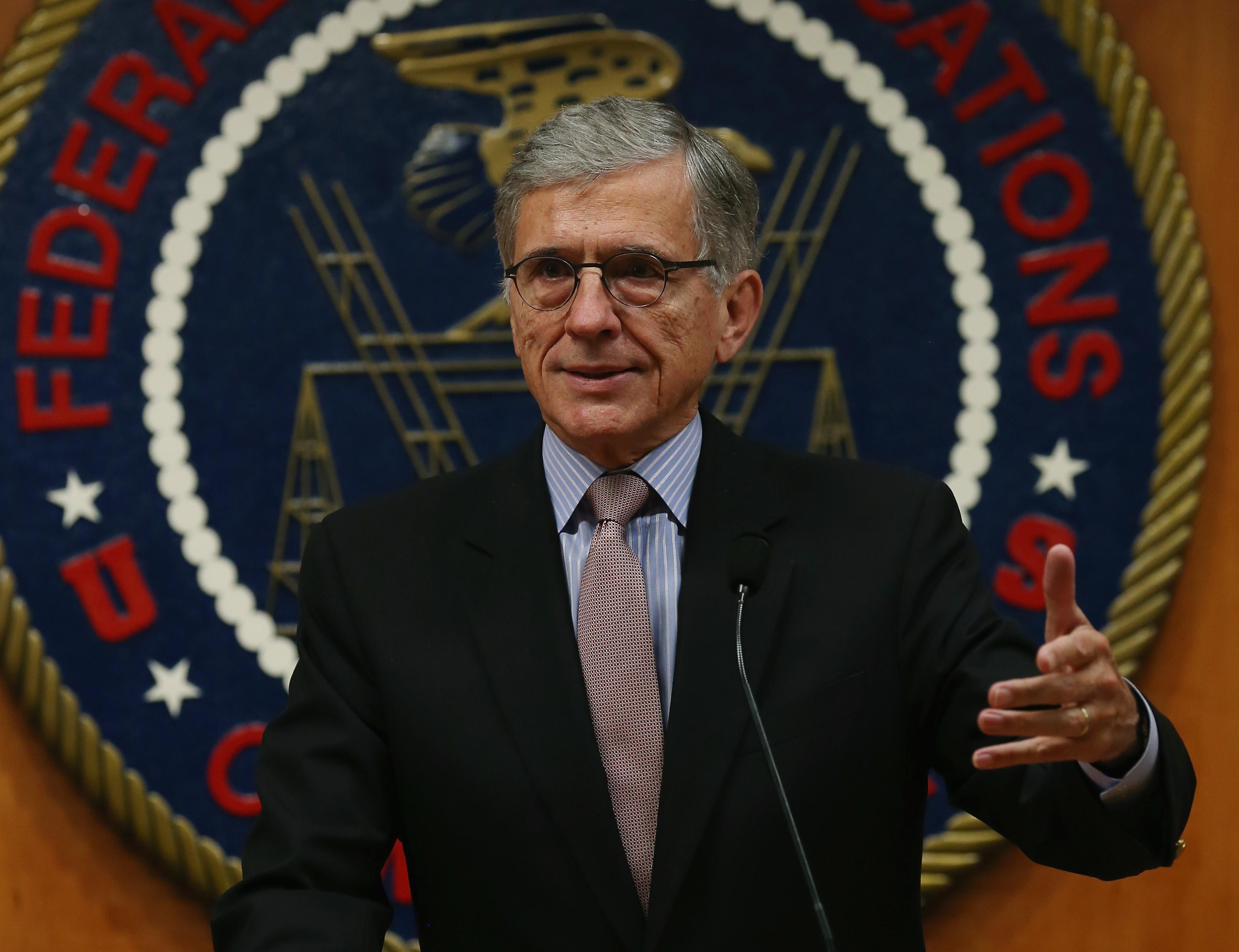

It looks like I was wrong about Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler—and there’s not much that could please me more.

Last April, I overflowed with cynicism about a trial balloon coming out of Wheeler’s office. This proposal, for Internet “fast lanes,” would have been an explicit defeat for the open Internet. If allowed, it would have been a capitulation to Big Telecom, giving the rapacious Internet access cartel just what it needed to turn the Internet into a 21st-century version of cable television, and ultimately force the rest of us to ask permission to communicate or innovate in the digital sphere.

In a Guardian column slamming the entire idea, I repeatedly attached “former cable and wireless industry lobbyist” to Wheeler’s name, to make clear why I thought he was doing this. But I also hoped the proposal would spur the rest of us to get busy, to do everything we could to block this move and instead push Wheeler and the FCC toward a different policy: reclassifying the dominant telecom-company Internet service providers as “common carrier” utilities and requiring essentially neutral treatment of the bits of information they transport.

Today, we know that Wheeler intends to do precisely that. In a Wired.com article under his byline, he writes:

I am submitting to my colleagues the strongest open internet protections ever proposed by the FCC. These enforceable, bright-line rules will ban paid prioritization, and the blocking and throttling of lawful content and services. I propose to fully apply—for the first time ever—those bright-line rules to mobile broadband. My proposal assures the rights of internet users to go where they want, when they want, and the rights of innovators to introduce new products without asking anyone’s permission.

There weren’t a lot of details in Wheeler’s commentary—and we all know how fine print can mock press releases—but he made this clear: He’ll ask his fellow commissioners use what’s called “Title II authority” to classify broadband carriers as common-carrier utilities. He noted that the Internet took off in the first place because the phone companies—the first communications systems used by the general public to connect to the Net—were not allowed to discriminate when providing access. He recounted his own experience years ago, as head of a startup that wanted to provide data over cable-TV lines and was thwarted by companies that were allowed to pick winners and losers. And he vowed to promote genuine competition, not regulation, as the best long-term solution.

So: I was wrong. And, for now, I am relieved.

What happened? I can’t say whether Wheeler personally had a change of heart, or whether this was a Machiavellian plan all along, or he was genuinely open-minded. I do know that in the months since April, the general public caught on for the first time that something essential to their future was being decided. Spurred by open-Internet advocates, the public spoke up. Never has an issue attracted so many public comments at the FCC, for example, and the comments were overwhelmingly in favor of protecting the net.

A tipping point occurred late last year when President Obama came out strongly for the open Internet, and he reiterated that position in his State of the Union address in January. The public was winning the battle of ideas, but the real fight was always going to wind up in Washington bureaucracies and corporate boardrooms.

One of the most important aspects of Wheeler’s proposed rule-making is extending the net neutrality principles to wireless networks, which increasingly—and in some ways alarmingly—are the method by which people go online. Too few countries have insisted on mobile net neutrality, and it’s gratifying to know that the FCC intends to ensure it here.

That’s a key word: “intends.” Even if the FCC votes for these rules, it’ll face an onslaught of opposition from the telecom giants and their congressional water-carriers. Look for the promised lawsuits to commence before proverbial ink is dry on the FCC order. Meanwhile, congressional Republicans, demonstrating epic hypocrisy as they so often do, are insisting that an unregulated cartel is just what America needs, all evidence to the contrary.

Moreover, we should recognize the very real can of worms in reclassifying the broadband carriers as utilities, assuming that it’s upheld by the courts and that future Congress and White House don’t repeal it. Like many other open-net believers, I’m deeply worried about unintended consequences. Wheeler promises a light touch in regulation, but he can’t hold his successors to that.

I’m especially hoping that Wheeler means what he says about spurring more competition in the broadband arena. A sensible answer has always been to create taxpayer-funded deployment of fiber networks everywhere, and then to open them up to any ISP that wants to serve any customers. Since that’s exceedingly unlikely, the next-best option is to force the telecom companies to let others provide ISP service through a leasing arrangement that ensures fair access to competitors; unfortunately, Wheeler renounced this possibility in his Wired piece. Enforcing common-carrier rules is my least-favorite solution, but it’s way, way better than nothing, which was where we were headed.

Meanwhile, the FCC should be doing everything in its power to let innovators do more with wireless spectrum. We’re living with antiquated rules based on antiquated technology in this arena, and almost nothing has been done to fix this.

For now, let’s savor a moment of progress for a cause worth fighting for: an open communications system for the Digital Age. Because what’s at stake is nothing less than freedom of speech, and the freedom to innovate.

And, one more time, to Wheeler and his team: I say mea culpa, and congratulations.