As the attack on French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo has evolved and sparked other violence in France, more and more people, groups, and companies have been expressing support for the victims. These messages, which often include the hashtag #JeSuisCharlie, are a statement of solidarity and strength in the face of violent censorship.

Charlie Hebdo itself decided not to pursue creation of an iPad app in 2010 because a development company told the publication that its content would be subject to approval by Apple, and that not everything would make the cut. Charlie Hebdo Editor-in-Chief Stéphane “Charb” Charbonnier said in 2010, “A company came to our doorstep to develop our app. But eventually the guy explained to us that we wouldn’t get the final cut of the publication on iPad. So we told them to get lost. … It was mainly about certain drawings that were judged to be outrageous that risked not passing the censorship bar.”

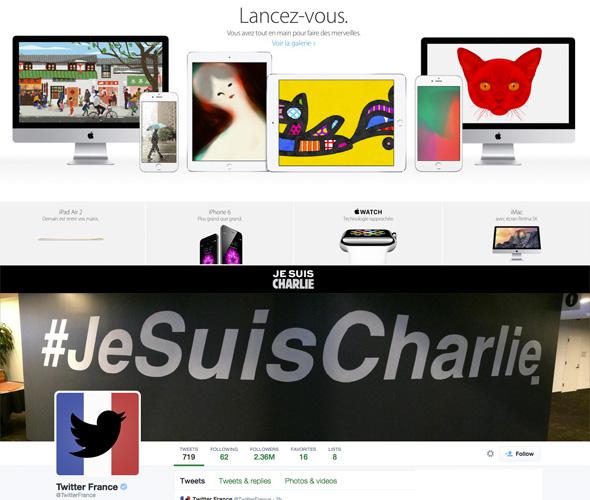

A Google-backed fund raised almost $300,000 this week to support Charlie Hebdo in printing a planned 1 million copies of its next issue. Apple and Twitter both added banners to their French sites/accounts. And Mark Zuckerberg wrote a blog post. In it he says:

Facebook has always been a place where people across the world share their views and ideas. We follow the laws in each country, but we never let one country or group of people dictate what people can share across the world. … I’m committed to building a service where you can speak freely without fear of violence.

Of course the fact is that every large communication platform deals with real and persuasive censorship pressure. Facebook recently censored a Russian page that was rallying against President Vladimir Putin. (Later Facebook and Twitter agreed not to block similar pages in the future.) In August, Twitter promised to suspend any user account that shared images or videos of journalist James Foley’s beheading by the terrorist group ISIS, and Google is often accused of things like keyword exclusion in search results or overstepping in its implementation of Europe’s “right to be forgotten” laws.

“All social media platforms always retain the right to ban you and to take down what you post,” said Kelly McBride, co-editor of The New Ethics of Journalism and vice president of academic programs at the Poynter Institute, in August. She added:

Social media has been around for a relatively short period of time, we have a pretty good idea of what its role is in democracy, but the people who create the guiding principles at social media companies—the codes of ethics that allow you to carry out your core values when there might be a conflict between those core values—the people who make those decisions, haven’t had a lot of time to develop true guiding principles.

Welp, here’s another good opportunity, everyone.