Have you ever clicked a link to a fantastic-looking website, only to have that buzzkill browser message pop up, telling you the site might have malware? Be honest: How often do you listen, and how often do you scoff and continue anyway?

Ask people how careful they are about cyber security and malware, and they’ll probably say they’re pretty cautious. But their actual behavior doesn’t always correlate—in fact, a new study recently published in a special issue of the Journal of the Association for Information Systems found people can be surprisingly cavalier. Unless cyber security has been brought to the forefront of our minds, our behavior is often inconsistent with how much we say we care.

Bonnie Anderson, Brock Kirwan and Anthony Vance, who are researchers at Brigham Young University, conducted their experiment with 62 participants. First, everyone took a pre-test and reported, among other things, how concerned they were about malware and cyber security. Weeks later, they performed the Iowa Gambling Task—an exercise frequently used to gauge decision-making and risk aversion. Kirwan measured the subjects’ brain responses to risk during the gambling task using EEG.

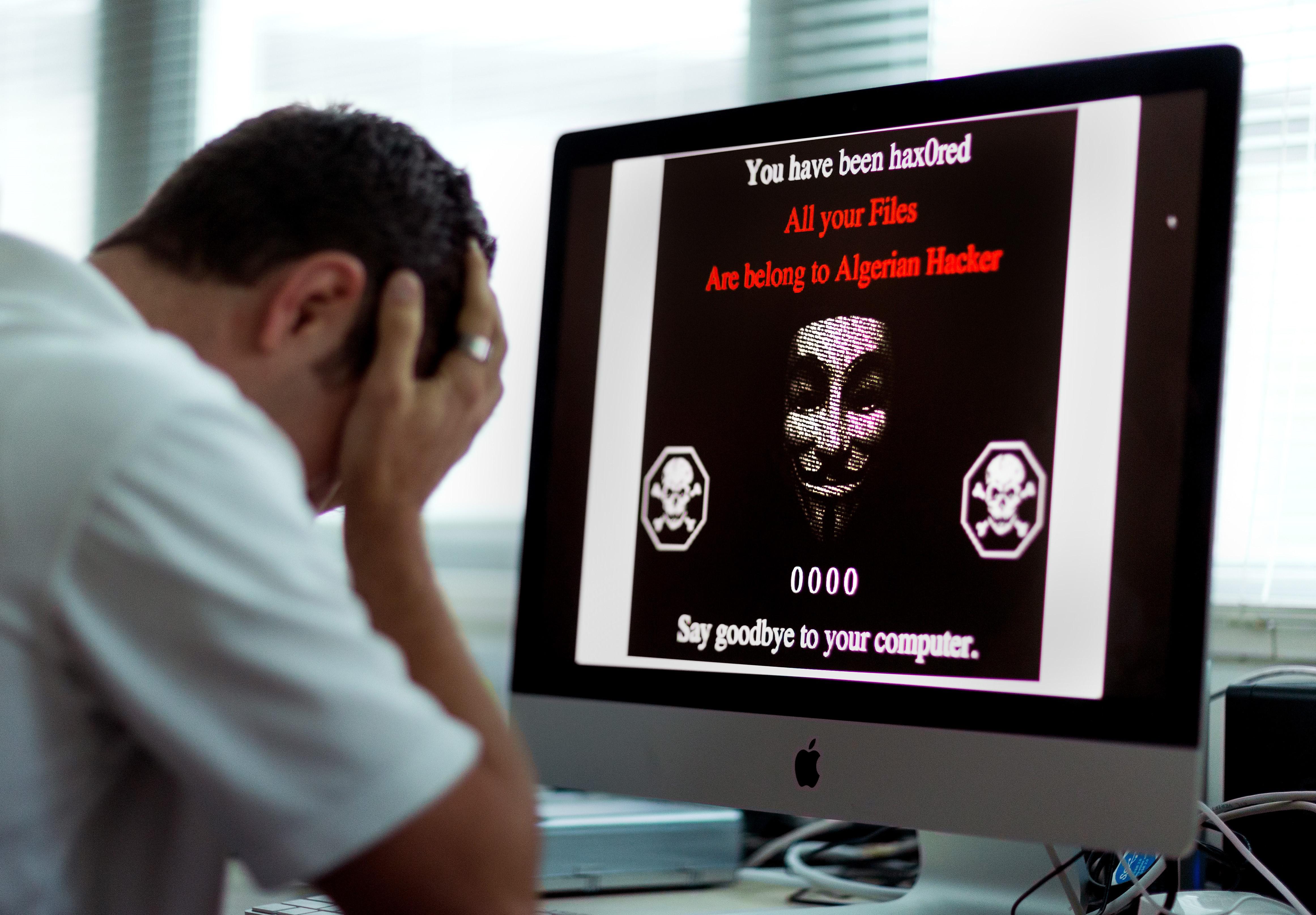

Finally, participants logged on to a website to classify images of Batman as either animations or photographs. They were told they were testing an algorithm’s accuracy in doing the same thing—but in reality, they were being tested. As they navigated from page to page, malware warnings intermittently popped up. If a participant ignored seven threats, a scary page popped up saying an Algerian hacker had broken in: “Say goodbye to your computer” appeared under a timer counting down from 10 seconds, complete with cackling skull and crossbones and an ominous Guy Fawkes mask.

To make sure the students had “skin in the game,” Vance said they were asked to use their own laptops. Unsurprisingly, the users who thought they were hacked were sufficiently freaked out. The study press release noted several participants alerted researchers that something bad had happened. Even participants who said they took cyber security seriously often cruised through malware warnings. Those who had the scare were more cautious afterwards—at which point their behavior matched their self-reported levels of concern.

Interestingly, subjects’ risk aversion, as calculated from the Iowa Gambling Task and EEG results, was a better predictor of their online cautiousness than their self-reported concern. Vance said EEG, which is recording of electrical activity along the scalp, is used routinely in research. But “EEG does not reliably measure emotions or intellectual activities,” said Selim Benbadis, a professor and director of the University of South Florida’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Program. Benbadis, whose research and clinical interests include EEG, said the technology is “used routinely in neurology to help assess various neurologic diseases,” but says it can’t monitor brain responses to risk, or the Iowa Gambling Task.

But the EEG use seems peripheral to the study’s main finding: that regardless of how security-conscious subjects claimed they were, their behavior often disagreed.

It’s easy to forget about online security and other mundane hazards. With scare-giants like mass shootings and Ebola, who has the time or emotional bandwidth to worry about malware and other small nuisances? The problem, of course, is that your computer is far more likely to contract malware than you are to contract Ebola. And the good news is that most browsers are already programmed to prevent us from exposing our computers to catastrophe—all we have to do is actually listen.