To say there’s been a bit of discussion for the last 10 months or so about the polar vortex would be an understatement the size of the Arctic. The phrase is now a permanent part of our wintertime vocabulary.

But the term is also somewhat nebulous. That’s led some journalists and meteorologists to get pretty bent out of shape about its resonance in popular media, even coining an unwieldy hashtag: #StopPolarVortexAbuse.

With record-breaking snow and cold from Minneapolis to Memphis and countless points in between already this month, it’s no surprise the “polar vortex” chat has come rushing back. Just a few days ago, AccuWeather offered up this whopper of a headline: “Polar Vortex to Blast 200 Million People With Arctic Air.”

When compared with seasonal averages, the current Omega Block-fueled cold snap is on par, if not even more severe than, the original polar vortex cold air outbreak in early January. There’s more snowfall on the ground right now in the United States than there usually is on Christmas Day. But does that a polar vortex make?

Last week, Jason Samenow of the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang proposed a science-based solution to the polar vortex linguistic impasse:

To be sure, the polar vortex is involved in this week’s cold snap—like it is in most cold snaps involving Arctic air. But this is not one of the more rare, high impact cases in which a huge chunk of the vortex breaks off and charges towards the U.S.-Canadian border bringing exceptional cold.

My view is that, to guard against overuse of the term, we should reserve calling special attention to the vortex to those cases in which its behavior is extreme.

So what separates polar vortex extremes from run-of-the-mill cold snaps? To find out, I called up NASA scientists Lawrence Coy and Steven Pawson, whose work focuses on predicting major disruptions of said vortex.

Their work takes advantage of a new class of weather models suited to monitoring the stratosphere, where weather balloons and satellites are producing data that is helping advance knowledge of the polar vortex and its implications for winter weather.

The roots of extreme, high-impact cases lie in the stratosphere, dozens of miles above the ground, where the polar vortex typically spins around the North Pole, a byproduct of the Earth’s rotation. Normally, a strong jet stream encases the hemisphere’s truly coldest air to the north. A few times a year, the vortex’s spin is perturbed from below by an especially exaggerated kink in the jet stream, and that hold weakens. This is what happened last winter, when a persistent ridge of high pressure off the West Coast of North America shunted the jet stream to the far northern reaches of the Arctic—and then back down again, taking square aim at the eastern half of the country.

This past January, Pawson says, “there was a pretty strong relationship. The shape of the vortex was distorted all the way from the surface right into the stratosphere. Those very cold weather features were propagating around the edge of a very deep vortex that you could see very clearly in the stratosphere.”

But sometimes, it’s precisely the opposite, said Pawson: “The weather is really pulling the vortex down. It’s not the stratosphere causing that to happen.” In these cases, dips in the stratospheric portion of the vortex will follow extreme cold air outbreaks at the surface, not precede them. Figuring out which disruptions in the stratospheric circulation will shift weather patterns on the ground is the forefront of polar vortex science.

Occasionally—about once every other year or so—the perturbation is so pronounced that the vortex breaks down completely. Scientists call these “sudden stratospheric warming” events, when a continent-sized chunk of rapidly sinking air (usually over Eurasia) quickly heats up and disrupts the polar circulation, sometimes completely disintegrating it. Statistically, that’s when the cold air floodgates can really open as the jet stream scrambles to contain the chaotic swirls of polar air that descend southward in the aftermath. In seven of the past nine sudden stratospheric warming events, the Washington, D.C. area, for one, has been colder than average for weeks afterward.

The result, Pawson told me, isn’t necessarily a one-to-one link from the stratospheric disruption to a blast of cold at the surface, but more of a tilt in the odds favoring extremely cold weather. “If you have a weather system developing, if one of these stratospheric events happens, and that all aligns, that can actually make them grow much faster than they might do otherwise.”

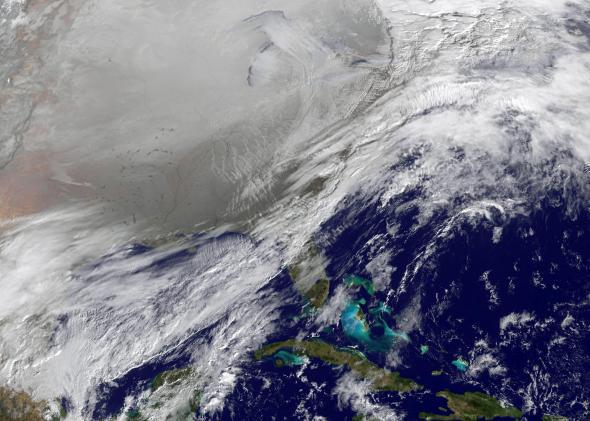

This happened most recently in January 2013—a full year before the polar vortex hit the mainstream in the American lexicon. An animation of satellite imagery taken at that time is nothing short of spellbinding. Watch:

The cold air outbreak associated with this sudden stratospheric warming event led to a colder-than-average February, marked by a huge East Coast blizzard. But that doesn’t mean Americans usually get the worst blow: Coy says that the U.K. and Europe “often have cold weather after a sudden [stratospheric] warming,” said Coy.

Previous research has shown a link between polar vortex destabilizations and global warming, and a recent increase in stratospheric warming events may be linked to melting Arctic sea ice and climate change. But Coy says it’s probably too early to tell for sure. Since Arctic ice has only been in a sharp decline for a decade or two, it’s hard to look at just a couple of years of data and know what’s going on. “You’d need a hundred-year modeling study,” says Coy.

Pawson and Coy are currently working to use today’s supercomputers and advanced models to reprocess an archive of old satellite images. Coy added, “I’m hoping to see something exciting this winter.”

He may get his wish. A huge stratospheric warming signal is already showing up for early December, though it’s still too early if it means a total polar vortex collapse or just a shift in its location.

If it’s the former, next month may portend a continuation of this already historic start to winter.