The plot of sci-fi blockbuster Interstellar focuses primarily on space exploration, black holes, and time travel, so it isn’t surprising that a lot has already been written on the movie’s portrayal of science—there’s even a book out already on the topic. What’s been discussed less is Interstellar’s portrayal of artificial intelligence and robotics, probably because the movie’s robots work so well that they never run amok and steal the show. Beyond bucking sci-fi stereotypes, though, Interstellar’s portrayal of AI illuminates several features of what our future with robots should (and shouldn’t) look like. (Warning: There are spoilers galore in the rest of this post.)

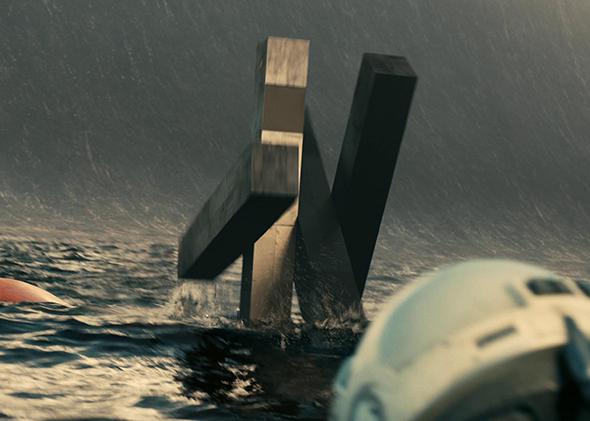

TARS, the main robot featured in Interstellar, looks nothing like a human. It also looks nothing like most robots in existence today. Sci-fi movies typically imagine robots that, like the iconic C-3PO, look roughly human-like (e.g. having two legs, two arms, and a face-ish thing up top, even if it is clearly not a human face).TARS, in contrast, doesn’t really have legs or arms or any other recognizable telltales of a biological organism. It reflects a different approach to the development of robots, more common among real-life roboticists than those apparently working in most science fiction universes, that puts function above humanness in the design of technology. True, some humanoid robots are currently in development, but favoring function over a familiar face may actually be in the interest of humanity. TARS’s last-minute rescue of Dr. Brand would have been impossible with a humanoid design, for example.

At the same time, TARS is no toaster. It speaks in fluent (if sometimes awkward) English and makes valuable contributions to the mission on a regular basis. In this regard, TARS is a model for a system that is user-friendly (combining fluid natural dialogue with common sense) while not seeking to re-create the physical and cognitive limitations of humans. It is commonplace these days for commentators (particularly those in the tech sector) to argue that technology complements rather than replaces human skills, but TARS shows how this is a false dichotomy. In order for it to do an adequate job of assisting humans, TARS needs certain humanlike functionalities, such as the ability to speak and understand language, but it needn’t be precisely made in man’s own image, either. An army of TARSes, even if not designed to replace or imitate humans, would have enormous practical applications.

The rights and needs of robots are another common theme in science fiction, and the source of a lot of plot conflicts. Consider, for example, science fiction futures that portray robots as looking and feeling just like humans someday, like in the movies A.I. and Bicentennial Man.

Interstellar makes no such assumptions. Rather, TARS is portrayed as a complex tool that performs a role similar to another crewmate on the ship but has none of the rights afforded to humans. Indeed, TARS once explicitly states that it is required to follow orders from humans, and that consequently its heroic sacrifices aren’t as heroic as they seem. Time and time again, TARS saves humans without any regard for its own self-interest except insofar as its survival is important to humans’ survival. This mirrors the recommendations of many of those interested in the ethics of AI and robotics. Cognitive scientist Joanna Bryson, for example, argues that imbuing robots the ability to suffer as a result of how they are used is a choice, and one that we have good reasons not to make. Between now and the time when building something remotely similar to TARS will be possible, we will probably learn a lot more about the nature of conscious experience in humans and other animals, and the possibility of replicating it in machines. For now, there are some early signs from research on consciousness to suggest that digital computers may never be able to experience conscious thought, and consequently TARS’s treatment as a mechanical slave is justified.

A final characteristic that makes TARS a valuable role model for robots in the real world is its relative transparency compared to existing technologies. That is to say, it is not only able to explain its decisions in terms that humans can understand, but it also is able to accept inputs from humans that alter its decision-making at the most basic level—for example, its “honesty parameter,” which seems to range from zero to 100 percent. By being transparent, TARS not only is more useful and customizable, but it also avoids many of the risks associated with AI in typical science fiction plots.

In particular, TARS never runs amok the way HAL does in 2001 or Skynet does in Terminator. This is not just because TARS has no survival instinct. An AI or robot doesn’t have to be selfish in order for it to pursue its goals in unexpected and dangerous ways. There are considerable technical challenges in developing a machine smarter than humans and keeping it under control. As we move from a world with a vast spectrum of dumb to somewhat smart machines in narrow domains, to a world of more TARS-like general-purpose intelligent machines, it is important that we understand exactly what the assumptions built into AI’s and robots’ software are, the context in which they are safe to operate, and so forth, for which bidirectional communication and understanding will be absolutely essential.

While TARS has a few good laugh lines and impressive moves in Interstellar, it is not the star of the show. And that’s the point. If we can creatively and responsibly develop technologies that fit well with human needs and govern them appropriately, there will be no need for real-life malevolent robots like HAL in order to make things interesting—rather, as Interstellar imagines, we can have a truly human-centric future that puts technology in its place.