Iowa sends farmers to Washington. Texas sends cattle ranchers. Why doesn’t Silicon Valley send a techie?

It isn’t for lack of trying.

On Friday, Ro Khanna, a 38-year-old technology and intellectual property lawyer, conceded defeat in his bid to represent the heart of Silicon Valley in Congress. He narrowly lost to Mike Honda, the 73-year-old incumbent, despite spending more than $4 million raised from the likes of Google’s Eric Schmidt, Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg, and Yahoo’s Marissa Mayer.

Honda’s hard-fought victory reveals that the Silicon Valley of Election Day remains a markedly different place than the Silicon Valley of popular imagination.

Both candidates were Democrats. But Khanna had styled himself as a dynamic young problem-solver who could bring fresh ideas worthy of the nation’s capital of innovation. His platform included creating jobs in the 3-D printing and robotics sectors and teaching kids to code. His campaign enlisted some of the minds behind Obama’s high-tech 2012 run, and he quickly drew the backing of the region’s tech giants. Here’s billionaire Sean Parker, of Napster and Facebook fame, endorsing Khanna at a swanky fundraiser in May:

We feel for a long time that Silicon Valley just hasn’t been properly represented at a federal level. We haven’t had the young, dynamic, hard-driving candidate that really understands the unique issues facing Silicon Valley right now. … I think we’re starting to come into a realization of our own power and our own capability, not just as innovators and technology pioneers, but also in a political sense.

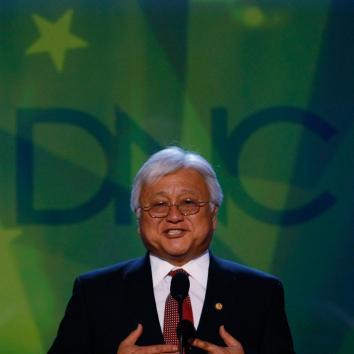

Honda, in contrast, is a seven-term incumbent from an older guard of liberal politics. His support came heavily from labor unions, and his campaign sought to portray Khanna as an elephant in donkey’s clothing. Whereas Khanna is a recent transplant, attracted to the Bay Area by its booming tech economy, Honda’s roots in the region date to a different chapter in its history. As a baby, he was shipped with his family to a Japanese American internment camp, and his parents worked as strawberry sharecroppers in San Jose back when Silicon Valley was a hub for agriculture rather than the Internet. Honda embodies Silicon Valley’s heritage as much as Khanna embodies its changing face.

Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images

In many ways, Khanna’s showing was impressive. He captured some 47 percent of the vote against a relatively popular incumbent from his own party.

Yet given his high-profile backers and huge war chest, his defeat will go down as another rebuff by Silicon Valley voters of tech-industry values. In 2008 renowned intellectual property lawyer and tech darling Lawrence Lessig opted not to vie for the late Tom Lantos’ San Mateo-based seat in the face of overwhelming support for his prospective opponent, longtime local politician Jackie Speier. (Lessig endured another political setback this cycle, as his $10.6 million campaign-finance-reform push fizzled.)

Young Silicon Valley types have also struggled in local and state races. An acquaintance of mine, Kai Stinchcombe, mounted a brief run for State Assembly in 2009 as a 26-year-old startup founder and Stanford grad student. He dropped out when another tech-friendly Democrat, 40-year-old Josh Becker, entered the race. Ultimately Becker lost too, despite raising the most money. The seat went to Rich Gordon, a 61-year-old veteran of San Mateo County politics.

I asked Stinchcombe, now 31 and the CEO of a fraud-protection startup for elderly people, why he thought the “tech candidate” approach hasn’t much resonated in the Bay Area. He pointed out that, for all their money and visibility, tech workers form a minority of the electorate even in Silicon Valley, and they can be perceived as entitled and out of touch.

“People in the tech world are not always as humble and self-aware as we should be about the role we play in society,” Stinchcombe said. “When we look in the mirror, we see people that are out there unambiguously doing good, saving the world. But your typical voter has a complex relationship with the tech economy. If you’re a low-income person living in San Francisco who sees the rent going up, or you’re in your 60s and 70s, which a lot of voters are, you might not look at Facebook and say, ‘Wow, these guys are really making the world a better place.’ ”

What Silicon Valley techies sometimes overlook, Stinchcombe added, is that they don’t necessarily need to put a software developer or an IP lawyer in Congress in order to have their interests represented—any more than Hollywood needs a movie star or Wall Street needs an investment banker.

He pointed to 66-year-old Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-California, who just won her 11th term in the San Jose-based district adjacent to Honda’s. In many ways, he said, “Lofgren has been a more effective advocate for the tech community than the tech community has. During SOPA and PIPA, she was the one telling Google” to get its political act together.

That said, Honda does not quite share Lofgren’s tech savvy, and Khanna has not ruled out another run. Larry Gerston, a political science professor at San Jose State, told the Mercury News he expects to see more Khanna-style candidacies in the years to come. “The Silicon Valley model is: If it doesn’t work the first time, tweak it and try it again.”