Does the Internet ever sleep? Not if you live in America: A new paper from John Heidemann and his colleagues at the Information Sciences Institute (ISI) at the University of Southern California shows that, in the U.S. relentless online participation is not just an inevitability during normal waking hours, whether you’re a 3 a.m. news junkie or you work for a corporate office where antivirus software updates at night.* But there are places where the Internet does sleep, as ISI discovered by tracking more than 500 million public IP addresses throughout the world.

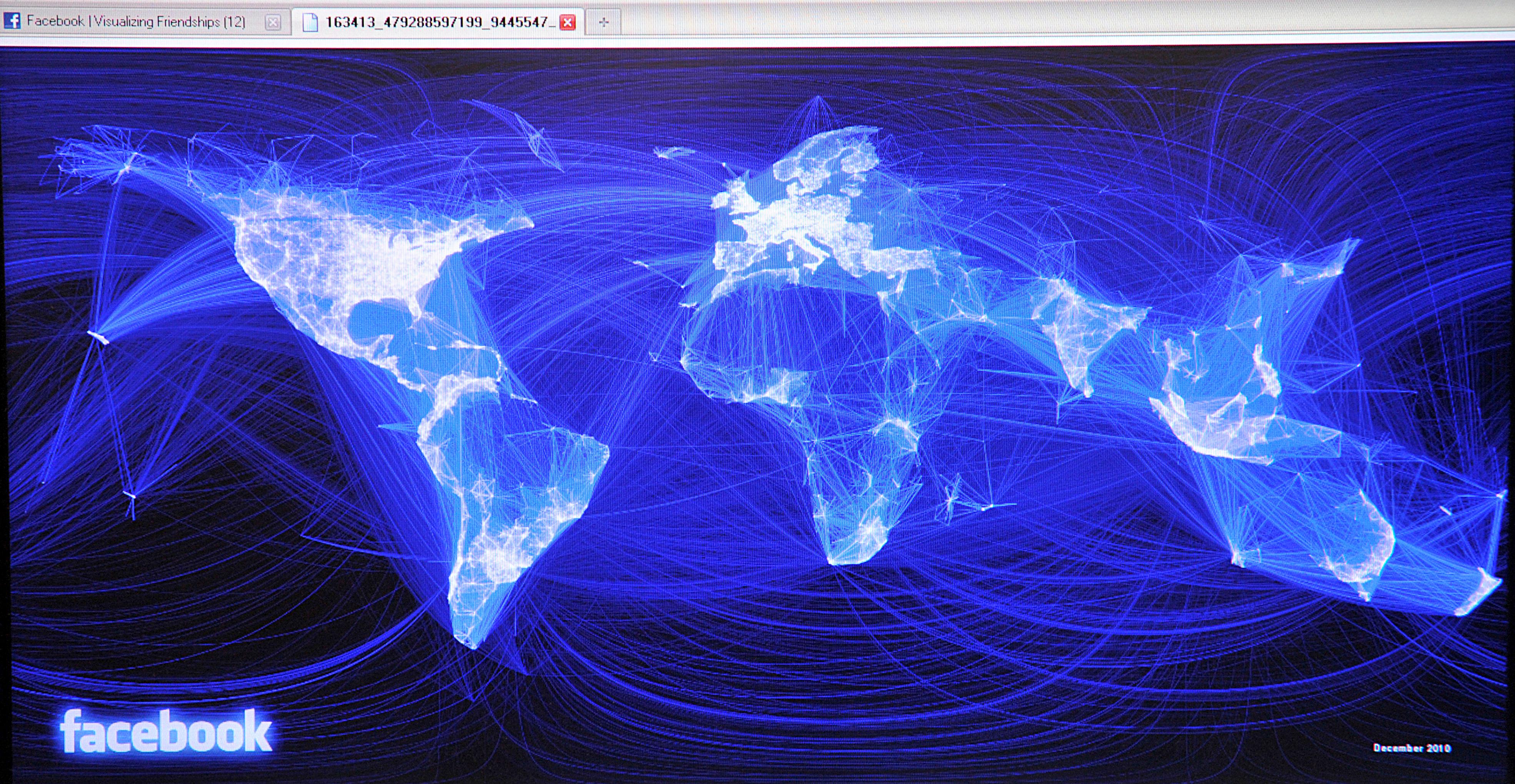

Heidemann and his colleagues looked at variations and patterns in public, active IP activity around the globe over 24-hour periods. Naturally, there are times when connection surges or wanes throughout a day, but after accounting for daily schedules, the researchers found that ebbs and spikes are more likely to occur in particular places, following what Heidemann calls a “diurnal” network usage pattern. As shown in the animation below, some parts of the world have stable, continually active IPs, with less than 5 percent change over the course of a day (areas in white), whereas in Asia, Eastern Europe, and South America, IP activity increases during the day and decreases during the night (areas in red or blue).

Variation is greater in countries with lower per-capita GDP and electricity use, Heidemann found—unsurprising, since a poorer consumer would likely have less constant access. She might go to an Internet café, which may be open for service only during certain hours, or she might turn off her home Internet connection at night to save on fees. By contrast, in the rich economies of Western Europe and North America, modems are generally left constantly running (so a public IP is still active), though you might shut off your computer (turning off your private IP, which Heidemann does not track). Infrastructure and governance make a difference, too: Places with “Internet maturity,” the researchers note, are marked by network access that is always on. (Part of the FCC’s definition of “broadband” is a telecommunications system where a network is available at any time.)

Moreover, there is greater commercial connectivity in rich economies as compared to poor ones. While people access the internet mostly during the day, Martin Libicki of the RAND Corporation points out that machine access is mostly at night—a company backing up its data into a cloud, say, or running algorithms for procurement is more efficient when there are fewer human users around. More of those activities probably contribute to keeping IP activity consistent over 24 hours; carrying them out depends on having continuous access.

Measuring the activity of global IP activity required that Heidemann and his colleagues probe a large sample within the pool of 4 billion public addresses. They did this by looking at 3.7 million “blocks” of IPs, where each block had 256 adjacent (sequentially related, and thus geographically close) addresses. Apart from a correlation with per-capita GDP, they also found that blocks with newer IPs were more likely to display diurnal activity. In less mature Internet blocks, there is more on-demand, dial-up connectivity, says Heidemann— an environment that drives periodic rather than constant activity.

The research cannot tell us exactly why IP activity stays steady in the West and regularly cycles in emerging economies. But a comparison of Internet robustness and usage between richer and poorer regions suggests the lack of quality and ubiquity are the two big reasons for variation. A mere 19 percent of Indians have Internet access, compared to 86 percent of Americans and more than 90 percent of Estonians, who declared Internet access a human right in 2000. (According to Heidemann’s study, Estonia’s Internet use is consistent—unlike much of Eastern Europe. Its per capita GDP is more than twice that of Belarus, where IP activity fluctuates by 15 percent each day.) Renesys (now a division of Dyn Research), an Internet security firm, ranks China and countries in Eastern Europe and South America to be at greater risk for connectivity outages.** In a world where commerce, knowledge, and wealth are increasingly exchanged online, investing in constant connectivity would be wise: Its adoption elevates activity and is a “direct driver of GDP growth in an economy.”

*Correction, Oct. 28, 2014: This post originally misstated John Heidemann’s first name.

** Update, Nov. 3, 2014: This post has been updated to clarify that Renesys is now part of a larger company, Dyn Research.