The National Weather Service, AccuWeather, and the Weather Channel all released their annual winter outlooks this week. They were all promptly torn to shreds by Gawker. Writing on the Vane, Gawker’s weather vertical, here’s the inimitable Dennis Mersereau:

NOAA released their long-range forecast this morning which calls for a warmer-than-average west and cooler- and wetter-than-average south, treating everyone else in the country to a wordier version of ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

He continues:

[M]ajor snowstorms are notoriously fickle—along the East Coast, especially, one town could receive a foot of snow while a town ten miles to the west gets nothing but a cold rain. The people who got the snow will remember it as a brutal winter, but the people who got the rain won’t remember the storm at all. You can’t predict that months in advance. Hell, it’s hard to predict that days or hours in advance sometimes.

What was released this week was not a 90-day weather forecast. Instead, seasonal forecasts aim just to show a tilt in the odds. And at that meager task, these kinds of outlooks do show historical skill—at least the government and research organizations that make their verification data publicly available. (The Weather Channel and AccuWeather do not.) These folks are hardly the Farmer’s Almanac. There is some science at work here.

Here are the highlights:

- The Weather Channel cites its own research linking above-average October snowpack in Siberia with a breakdown in the polar vortex later in the winter. Guess what? This year’s October snows in Siberia have been through the roof, running ahead of even last year’s near-record pace. Other forecasters have started to pick up on this correlation in recent years, too.

- The National Weather Service points to a weak El Niño signal as evidence that West Coast drought will continue, perhaps even strengthening from northern California to the Pacific Northwest. On the East Coast, the weather service is noncommittal, though it hints at an increased likelihood of coastal storms along East Coast by calling for above-average winter precipitation there.

- AccuWeather, big and bold as usual, is calling for the polar vortex cold snaps to “slip down into the [Northeast] from time to time,” though not as persistently as last winter. Its outlook, which last year called for “record-breaking warmth,” for the Tennessee Valley (a prediction that wasn’t even close), is switching its tune this year: If you live down South, be prepared for lots of ice this winter.

Seasonal weather forecasting has advanced to the point where the skill is comparable to a 6-8 day weather forecast: better than random guessing, but not quite something you can bank on. The predictions are used extensively by people like water managers in California who need to know how much water to release in dwindling reservoirs, or the Department of Transportation in Minnesota, which needs to know if it should stock up on road salt. Seasonal forecasts can tell you if the odds are tilted for or against cold or drought.

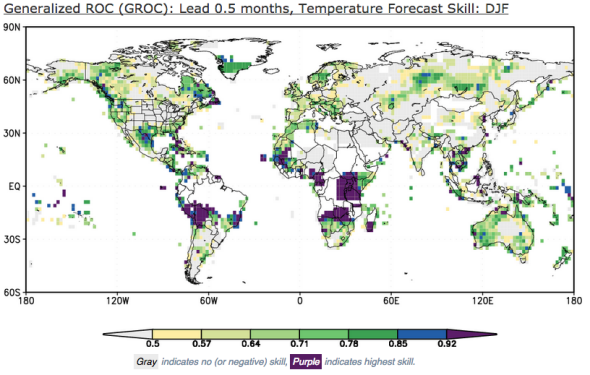

Columbia University’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society, which has pioneered the relatively new science of long-range forecasts, has a database of its global forecast skill since 1999. (Disclaimer: I used to work there, but not in the seasonal forecasts section.) Historical accuracy of the leading suite of seasonal forecast models used by National Weather Service is also available online.

The forecasts work primarily by tracking the development of slow-moving patterns of ocean temperature and then linking them with historical shifts in global weather. It’s a bit like how Target predicts you’re having a baby when you buy a bunch of unscented lotion and cotton balls: The ocean-atmosphere correlations have predictive skill when coupled with proven theories of how heat and moisture make their way around the planet over a timescale of weeks-to-months.

Forecasts for the December through March season have been among the IRI’s best performing outlooks of the entire year. During El Niño years (like 2014 should be), that accuracy increases even further. In the United States, there’s a swath of especially high winter-season skill from California to the East Coast.

Image: IRI

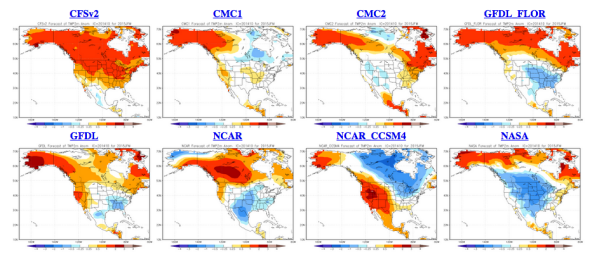

Looking under the hood at this winter’s forecast, five of the eight models the National Weather Service uses show a colder than average January to March along the East Coast.

Image: NOAA

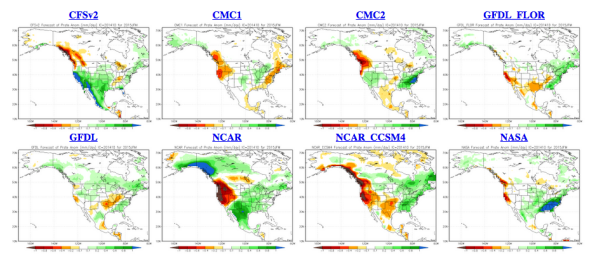

Six of the eight models show a wetter than average winter in the East.

Image: NOAA

And, as we all know, cold + water falling from the sky usually equals snow.