Over the next decade or so, our collective climatic future will be won or lost based on how aggressively the world decides to limit greenhouse gas emissions.

Increasingly, the greenhouse gas that could provide humanity’s biggest bang for its climate change tackling buck isn’t carbon dioxide—it’s methane. For the first time, a team of scientists have observed the effects of natural gas extraction—which is 95-98 percent methane—from space.

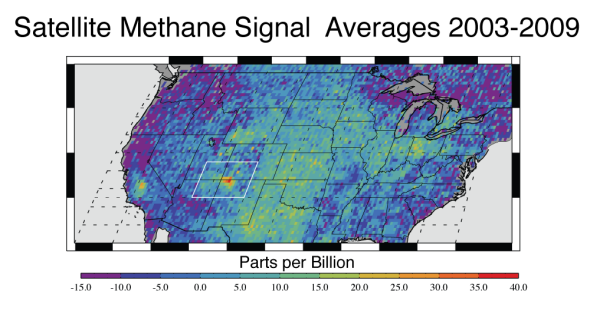

Using satellite data, a study published Thursday finds a surprising methane hotspot: New Mexico’s San Juan Basin, an area that some believe is primed for its own oil and gas boom just like the one a few years ago in the Bakken formation of western North Dakota.

“It’s the largest signal we saw in the continental United States,” said lead author Eric Kort, a professor at the University of Michigan. I reached Kort by phone Thursday.

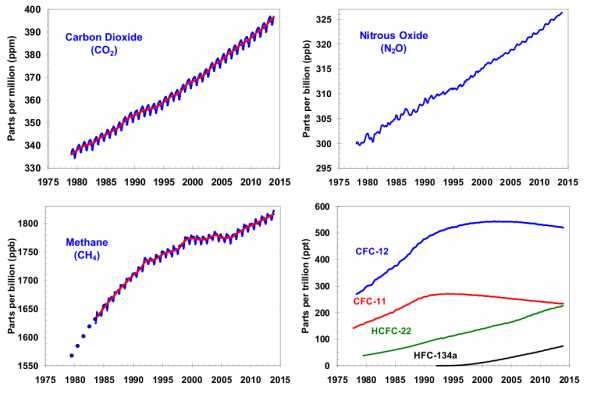

Methane has a shorter residence time in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, but once it’s up there, it’s a doozy. Pound for pound, methane is 20 times more effective at trapping the sun’s heat as carbon dioxide.

Since 2007, global methane emissions have steadily increased, but scientists aren’t sure exactly why. They’ve narrowed down the possible main sources to burps from a warming Arctic, an uptick in emissions from tropical wetlands, and human agriculture and fossil fuel extraction. The recent rise overlaps with the American boom in fracking in places like North Dakota, but also to an increase in Arctic temperatures.

Along with co-authors from NASA and the Department of Energy, Kort analyzed seven years of methane concentrations from the space-based high-resolution (and impressively named) SCanning Imaging Absorption SpectroMeter for Atmospheric CHartographY (SCIAMACHY), which is accurate enough to track anomalies back to their source regions.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Michigan

The San Juan Basin blip that Kort’s team found showed up during the entire seven-year dataset, and in all seasons—evidence that its source was likely unnatural. Intrigued by this finding, the authors decided to explore further.

In 2012, using ground-based measurements, they were able to track the anomaly back to an unconventional technique called coalbed methane extraction that’s been practiced for decades in the region.

However, in order to justify the anomalous atmospheric concentrations they were detecting, Kort’s team calculated the amount of methane emanating from these sites must be enormous: 590,000 tons per year, or about 10 percent of the EPA’s estimate of total U.S. emissions from natural gas production, and about three-and-a-half times higher than previous estimates in this region.

For perspective, Kort’s analysis shows the San Juan Basin may already be producing methane emissions roughly equivalent to the entire oil, gas, and coal industry in the United Kingdom. Said Kort, “it is a pretty impressive number from such a small spatial region.”

Earlier this year, the Obama administration announced an offensive on methane that relies primarily on voluntary compliance by the agriculture and energy industries. However, in September, the Department of Energy paved the way for increased natural gas exports at port facilities on the Gulf Coast, an example of the administration’s on-again-off-again commitment to making hard choices in favor of climate stability.

Kort’s not done examining the San Juan Basin. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is supporting his research team to conduct an aerial survey of the region in an attempt to further track down individual point sources of methane.