Earlier this year, the European Union’s high court ruled that private citizens could force Google and other search engines to remove links to Web pages that contain sensitive personal information about them. Since then, Google has received hundreds of thousands of such requests from people exercising their “right to be forgotten.” The Wall Street Journal reported in July that it has granted roughly half of them.

One of the more controversial effects of the law has been to force Google to effectively censor certain news stories in order to protect the privacy of people mentioned therein. BBC News and the Guardian are two that have seen old articles disappear from the Google results for some search queries.

European publications aren’t the only ones affected. On Friday, the New York Times reported that Google has removed links to five of its articles in the results for certain search terms on European versions of its search engine.

The good news, for those worried about censorship, is that these five articles are unlikely to be sorely missed by a large number of people. The bad news is that they represent such a seemingly arbitrary selection of stories that it’s hard to draw any conclusions about what kinds of journalism will be sent down the memory hole in the months and years to come.

The five stories are:

- Two wedding announcements from “years ago” whose subjects the Times did not disclose

- A brief paid death notice from 2001

- This 2002 news story by Jennifer 8. Lee about three companies that were accused of fraudulently selling nonexistent Web addresses

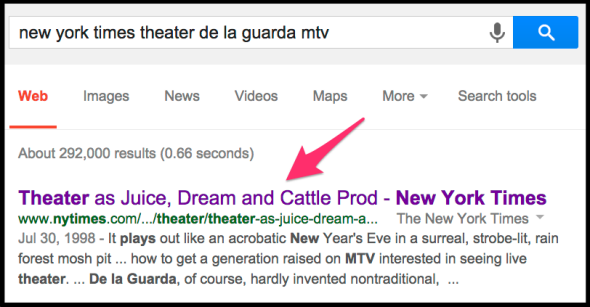

- This 1998 feature story about a peculiar off-Broadway theater production that managed to appeal to “a generation raised on MTV”

Principles aside, the removal of a few marriage and death notices from Google search results probably doesn’t pose an existential threat to journalism or democracy. It’s the other two articles whose removal is more worrisome.

As the Times notes, it’s not hard to see why certain people might have wanted the story about the false Web addresses scrubbed from their online records. Among those named in the story were two men from London who were said to have controlled the companies in question. The case was eventually settled, but presumably the defendants’ names remained attached to it whenever someone Googles them. Not anymore.

The real oddball, though, is that Theater piece about a production of Villa Villa by an ensemble called De la Guarda. The Times admits that it was “much harder to divine the objection” that someone must have raised with Google in order to get that one removed. Google itself won’t tell: It has a policy against divulging the names of those who request takedowns under the “right to be forgotten” law.

Here’s a wild guess, though. What if the request came, not from anyone involved in the production, but from one of the random young theatergoers who gave “man on the street”-type quotes to the paper after attending the show? One young person, for instance, was quoted in the following context:

”It was like a dream, only more intense,” said [name redacted], a 27-year-old art student who walked out into the night with a damp, disheveled, wild-eyed look entirely appropriate for a production a reviewer from The Guardian in London described as ”theater as good as sex.”

That was the person’s only appearance in the story. (I’ve redacted the actual name just in case my wild guess is right.) It’s a good quote, adding color to the piece, but it’s hardly essential. The author of the article, and probably just about everyone who read it, probably forgot her name long ago.

But Google hasn’t—and maybe she hasn’t, either. Maybe, benign as the quote might seem, it has haunted this person for years that everyone who Googles her sees a reference to her from 16 years ago as a “damp, disheveled, wild-eyed” 27-year-old emblematic of the ADD-addled MTV generation. If so, it would be hard to blame her for wanting the story to stop following her around.

For years newspapers have fielded the occasional request to remove a source’s name from the online version of a story, for just this sort of reason. Generally, in my experience, they refuse on principle.

But as someone who’s skeptical of “right to be forgotten” laws, I can see this as one place where they might do some good without doing much harm, depending on how they’re applied.

Specifically, if Google has removed a link to the article only from the results for searches for this one source’s name, that’s quite different from censoring the story altogether. Provided Europeans can still find the article by searching for “Villa Villa,” “De La Guarda,” “modern theater,” “live theater MTV generation,” and so forth, it would be no great loss if they can no longer find it by searching for the name of one individual theatergoer who happened to be quoted therein.

The problem is that Google won’t say which search results no longer return the story in question. And that’s emblematic of the broader problems with the law. The harm to people mentioned in newspaper stories that are searchable online is relatively easily demonstrated. In contrast, the harm inflicted to the public at large by removing those stories via an opaque and seemingly arbitrary process is impossible to gauge.