On Tuesday evening Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital reported the U.S.’s first diagnosed case of Ebola. The patient, Thomas Eric Duncan, first came in to Presbyterian’s emergency room five days before, on Sept. 25. He wasn’t admitted during his first ER visit, though, because of some type of miscommunication involving the hospital’s electronic record system and the staff. The incident is serving as a high-profile reminder that the nation’s medical computer systems aren’t really working.

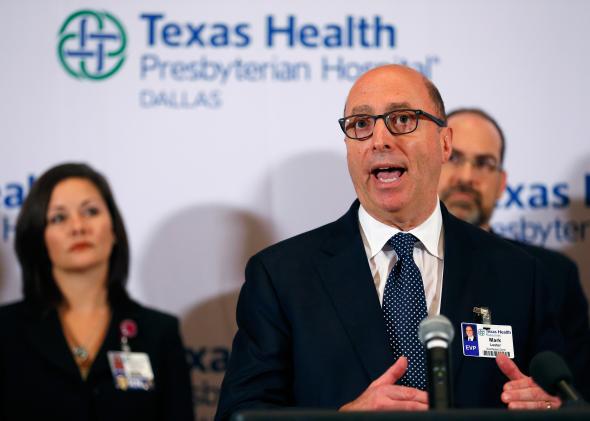

Texas Health Presbyterian said in a national briefing that it was prepared to deal with Ebola cases and had done a targeted staff training on Sept. 1. But when an Ebola case walked through the hospital’s ER doors, the plan somehow broke down.

As Politco points out, the hospital initially said in a statement on Thursday evening that the setup of its health record system was “flawed.” It said that Duncan did tell an intake nurse that he had recently come from Africa but this detail “would not automatically appear in the physician’s standard work flow.” If hospital staff had known that Duncan had come from Liberia (a country with one of the biggest Ebola outbreaks in Africa) only a few days before, they would have immediately admitted and quarantined him just in case his flu-like symptoms—a low grade fever and vomiting at the time—turned out to be Ebola. Which in this case they did.

CNN reports that on his first visit Duncan had basic blood work done but wasn’t tested for Ebola. He was apparently given antibiotics and pain medicine and sent home. “His condition did not warrant admission. … He also was not exhibiting symptoms specific to Ebola,” the hospital said.

The federal government has spent $30 billion on subsidies to roll out a national digital record system, but countless reports document health care workers’ discontent with the system and concerns about its reliability. For example, Deborah Burger, who is president of the California Nurses Association told the New York Times back in 2012 that, “The problem is each patient is an individual. We need the ability to change that care plan, based on age and sex and other factors.”

One issue is that the system is implemented differently at different health care centers so some things that seem like they should be standard don’t always appear. For example, Politico reports that at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, if a patient had recently flown from Liberia and a health care worker entered into the computer system that the patient had a fever, a yellow flashing alert would immediately cover the screen warning that the patient needed to be quarantined because of the risk of Ebola.

On Friday night, Texas Health Presbyterian issued a “clarification” of its statement from Thursday and said there was “no flaw” in how the different parts of its electronic record system had interacted. Since these two statements are contradictory, it’s unclear what actually went on and the hospital has declined to comment further for now.

Last year, two physician working groups from the American College of Emergency Physicians issued seven recommendations for improving digital record systems in ERs. Heather L. Farley, a member of one of the groups said in a statement that, “The rush to capitalize on the huge federal investment of $30 billion for the adoption of electronic medical records led to some unfortunate and unintended consequences, particularly in the unique emergency department environment.”