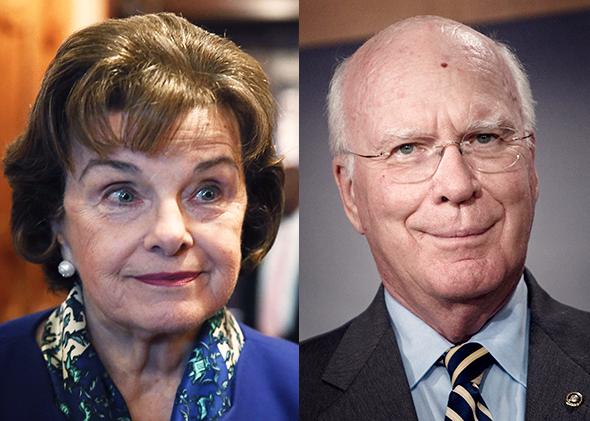

“It’s called protecting America,” Sen. Dianne Feinstein, chair of the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, asserted in June 2013. In the aftermath of the Snowden leaks, she has defended the domestic surveillance conducted by the NSA as something that has “not been abused or misused” and is “essential,” “necessary and must be preserved.”

The chair of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary offers a sharply divergent view. We “have to have some checks and balances before [we] have a government that can run amok,” Sen. Patrick Leahy said in January. He has warned that the NSA’s domestic surveillance could lead to “the government controlling us instead of us controlling the government.”

It isn’t just rhetoric: Both Feinstein and Leahy have taken action. Feinstein introduced the FISA Improvements Act, passed by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence on an 11–4 vote, which would provide explicit statutory authority for the NSA’s surveillance programs. In the other corner, Leahy introduced, with White House backing, the USA FREEDOM Act, which would strongly limit the NSA’s bulk collection of Americans’ records.

Nor is the split limited to the Democratic Party or the Senate: A similar divergence exists between the U.S. House of Representatives’ Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and Judiciary Committee (both Republican-controlled). In fact, the House intelligence committee introduced the FISA Transparency and Modernization Act (a bill somewhat similar to Feinstein’s FISA Improvements Act), while the House judiciary committee introduced the USA FREEDOM Act in that chamber.

One reason for the committees’ widely divergent views could lie in the fact that the House and Senate intelligence committees, as part of their responsibilities, are regularly briefed by the NSA in closed proceedings. The intelligence committees’ ability to conduct effective, unbiased oversight is inevitably limited by the fact that there is no built-in counterweight to the NSA’s perspective in these nonadversarial sessions. (The same thing happens with the intelligence committees’ judicial counterpart, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, or FISC.) Even when the intelligence committees or the FISC proactively invite independent outside experts to testify, those experts are usually only able to speak in general terms, since they don’t have access to the classified materials presented in the NSA’s briefings.

To address this imbalance at the FISC, President Obama has proposed creating (and the draft USA FREEDOM Act would codify) a panel of special advocates to argue in support of privacy and civil liberties in the court’s closed proceedings. That’s a good step, but it shouldn’t be limited to the FISC. The Legislative Branch’s intelligence committees need privacy advocates, too—the roles could even be filled by the same people.

As currently contemplated by the draft USA FREEDOM Act, the special advocates would be attorneys with expertise in privacy and civil liberties, intelligence collection, or telecommunications, jointly appointed by the FISC’s and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review’s judges in consultation with the independent, bipartisan Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board. The advocates would assist the FISC by serving as amici (friends of the court) in cases presenting a “novel or significant interpretation of the law,” arguing “in support of legal interpretations that advance individual privacy and civil liberties.”

Unlike outside experts, the advocates would be granted access to classified information relevant to their duties, allowing them to go beyond general principles and respond directly and specifically to each argument advanced by the NSA and its sister intelligence agencies. Further, in addition to participating in specific cases, the advocates would be periodically briefed by the attorney general on overall intelligence-related legal and technological developments, to ensure they remain aware of the “big picture.”

Little would need to be added or altered if the advocates’ role were to be expanded to include advocating before Congress’ intelligence committees. The appointment process would remain unchanged. (A few more advocates might be required to handle the greater workload, but this would not require amending the draft USA FREEDOM Act: It currently calls for a minimum of five advocates, but does not specify a maximum.) The advocates’ access to classified information, and their attorney general briefings, would also remain unaltered.

In fact, the only required addition would be a clause defining the advocates’ role before the intelligence committees. Based on the advocates’ role before the FISC, the advocates could be tasked to assist the intelligence committees by testifying in support of individual privacy and civil liberties in hearings considering either a novel or significant interpretation of the law or a change to the law.

Having special advocates provide an alternative to the intelligence agencies’ perspective would help provide the House and Senate intelligence committees with a more comprehensive view in performing oversight. There is room for disagreement on the merits of the NSA’s domestic operations. However, all sides agree on the importance of restoring the public’s trust in our nation’s intelligence agencies. Doing more to ensure fair and balanced oversight would take us one critical step closer to that goal.