When a woman experiencing domestic violence calls the police, it’s usually her last resort. Most cases of abuse go unreported, and those women who do call the police often go into hiding soon after. That first interaction between the police and the victim, then, is critical. Collect enough evidence at the initial encounter, and officers won’t need to force the victim to keep cooperating through the whole investigation. Prosecutors can use that evidence to mount a case in court to put the abuser behind bars—without forcing the victim to continually revisit her traumatic experience.

There’s one hitch to all this, though. Domestic violence frequently involves battering and strangulation, the primary proof of which is bruising. But bruises can take days to reveal themselves, especially for victims with darker skin tones. When cops arrive at the scene of the crime, the chief evidence of abuse may appear to be absent—and if the victim goes into hiding, prosecutors may never be able to gather the evidence they need to ensure that the abuser is jailed.

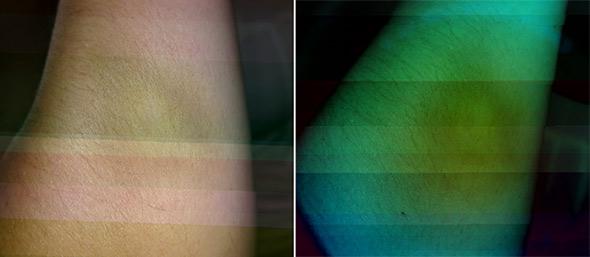

Enter the Illumacam-2, an LED camera that’s poised to change the way law enforcement officers across the country investigate and prosecute domestic violence. The Illumacam-2’s design is fairly simple: a camera with an alternate light source that utilizes different light spectrums—16 blue LEDs and 16 white LEDs—to capture enhanced images invisible to the naked eye. Recently, the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department bought six Illumacams for officers to bring on domestic violence calls. The purchase was made in conjunction with the Baker One Project, a partnership between the department and several domestic violence agencies, which aims to uncover and halt domestic violence before it escalates into homicide. Because the vast majority of women killed by their partners face serious violence for weeks, months, or years prior to their murder, early intervention is one of the most effective ways to save victims’ lives.

But victims of abuse (who are usually, but not always, women) are often hesitant to report the crime. Their reluctance arises for a variety of reasons—not least of which is the perception that police won’t, or can’t, do anything to help them. In one sense, then, the Illumacam is useful not just as a evidence-gathering tool, but also an assurance by the police that they’re serious about helping victims. A woman who reports her abuse to the IMPD can now be certain that, even if she must run for her life, the police may gather enough evidence at that first encounter to lock up her abuser.

According to Jennifer Reister, domestic violence projects supervisor at IMPD, the police have not yet witnessed an uptick in reports of abuse by victims; the Illumacam initiative is just too new to produce any concrete data. Since the foundation of the broader Baker One Project, however, Indianapolis has seen a measurable increase in domestic violence-related calls to local service agencies, suggesting that the increased visibility of the project is encouraging women to report their abuse. That’s hugely encouraging news. For too many years, police dismissed domestic violence as a fundamentally private matter. By investing in cutting-edge technology like the Illumacam, officers are finally proving to women that, yes, domestic violence is a crime—and, yes, the police are there to do something about it.