This piece also appeared in New America’s Weekly Wonk.

More than a year after the Snowden revelations, we’re clearly still grappling with the effects of NSA surveillance.

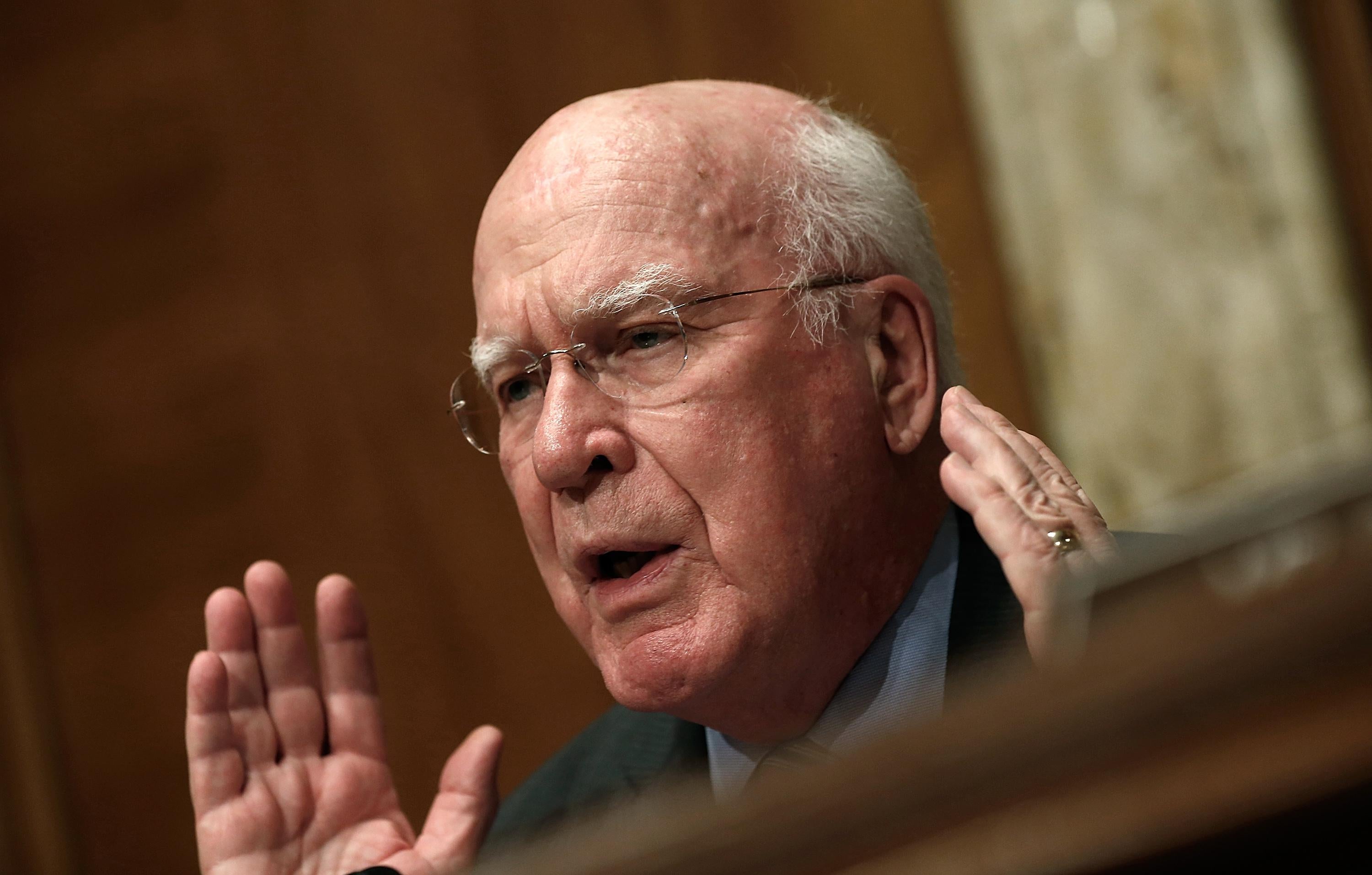

As Congress prepares for the August recess, Sen. Patrick Leahy has just introduced a new version of the USA FREEDOM Act, which aims to curb the NSA’s bulk collection and surveillance powers. Calls for immediate, serious reforms are growing louder by the day as new evidence continues to emerge about how much NSA surveillance is costing us—in terms of both the economy and our cybersecurity.

Intelligence and Obama administration officials have vigorously defended the NSA programs over the past year. But they have offered little hard evidence to prove the value of mass surveillance and other far-reaching NSA activity. Both the President’s Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technologies and the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) issued extensive reports that call into question whether the benefits of the NSA’s bulk collection program carried out under Section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act are enough to justify the tradeoffs. The PCLOB gave a more favorable outlook in the recent report on surveillance authorized under Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act—but those findings were almost immediately called into question by a Washington Post story that revealed that nine out of 10 Internet users swept up by Section 702 surveillance are not legally targeted foreigners. And these reports don’t even begin to grapple with effects of the extensive collection taking place outside of the country under Executive Order 12333.

Meanwhile, evidence of the costs continues to pile up. This week, two new reports were published that demonstrate how surveillance reform is needed to protect fundamental rights here in the U.S. An in-depth study conducted by the American Civil Liberties Union and Human Rights Watch documents how mass surveillance undermines press freedom, the right to legal counsel, and other essential elements of a healthy democracy. And a separate report from New America’s Open Technology Institute examines how the NSA’s programs are bad for the U.S. economy, American foreign policy, and the security of the Internet as a whole. (Full disclosure: I am the primary author of the second paper; Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University.)

It’s easy to get caught up in the simplistic debate that often dominates the surveillance conversation: that this is about balancing national security and individual privacy. But the binary argument over security vs. privacy ignores the other negative impacts of NSA surveillance on our national interests. The U.S. cloud computing industry—a fast-growing and American-dominated market—could lose anywhere from $22 billion to $180 billion in the next few years as companies lose customers abroad and here at home. U.S. tech companies are facing declines in overseas sales due to the backlash, while foreign governments are blaming the NSA for decisions to drop American companies from huge contracts, as we’ve witnessed with Boeing in Brazil and Verizon in Germany.

Beyond the dollars and cents, the Snowden disclosures have accelerated data localization and data protection proposals from foreign governments that are looking for greater national control over their citizens’ info. These proposals could create significant economic and technological hurdles for American businesses: It’s both more expensive and more difficult to house servers in specific countries in order to comply with data localization laws. What’s more, mandatory data localization policies can have a negative impact on Internet freedom and the protection of human rights in countries that do not have strong local protections against surveillance. In fact, the Snowden disclosures could broadly undermine the entire U.S. Internet Freedom agenda, which was a key component of American foreign policy under Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Lastly, there’s growing evidence that certain NSA surveillance techniques are actually bad for cybersecurity. As the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers recently explained: “The United States might have compromised both security and privacy in a failed attempt to improve security.”

We’ve learned in the past year that the NSA has been deliberately weakening the security of the Internet, including commercial products that we rely on every day, in order to improve its own spying capabilities. The agency has apparently tried everything from secretly undermining essential encryption tools and standards to inserting backdoors into widely used computer hardware and software products, stockpiling vulnerabilities in commercial software, and building a vast network of spyware inserted onto computers and routers around the world. A former U.S. ambassador to the U.N. Human Rights Council, Eileen Donahoe, wrote a forceful article back in March about how the NSA’s actions threaten our national security.

When you weigh these costs against the questionable benefits of the programs, the need to rein in the NSA and restore international confidence in the U.S. becomes obvious. The USA FREEDOM Act is “historic” not because it would solve all of our problems, but rather because it would be a much-needed first step in the long road to recovery from the effects of widespread NSA surveillance.