Late last week, helicopter video of a mysterious hole emerged in a remote part of northern Siberia, sending conspiracy theorists into a tizzy worldwide.

(Spoiler alert: Turns out, that last theory isn’t so far off.)

Now, a second hole has been found.

From the Moscow Times:

Reindeer herders in Russia’s Far North have discovered yet another mysterious giant hole about 30 kilometers away from a similar one found days earlier.

Located in the permafrost of the subarctic Siberian region of Yamal, which means “end of the earth” in the local Nenets language, both craters appear to have been formed in recent years and have icy lakes at their bases.

A new video released by the Siberian Times on Friday shows a brief glimpse inside the first hole as an impromptu scientific expedition visited last week.

According to a Siberian Times interview with the scientists, there’s a clear connection with climate change:

Anna Kurchatova from the Sub-Arctic Scientific Research Centre thinks the crater was formed by a water, salt and gas mixture igniting an underground explosion, the result of global warming.

Gas accumulated in ice mixed with sand beneath the surface, and that this was mixed with salt—some 10,000 years ago this area was a sea.

Global warming, causing an “alarming” melt in the under soil ice, released gas causing an effect like the popping of a Champagne bottle cork, she suggests.

It’s as if the Earth is celebrating. Soon, no more humans!

Around the time the first crater is estimated to have formed—2012 or 2013—temperatures were unusually high for that part of Siberia. In general, the whole Arctic region is the fastest warming place on the planet, warming about twice as fast as global averages. A study published last year said the Arctic hasn’t been this warm in at least 120,000 years.

As permafrost melt accelerates across the Arctic, there’s increasing concern that the natural release of methane and other greenhouse gases will also accelerate. Arctic permafrost in Alaska, Canada, and Russia holds more frozen carbon (in the form of both carbon dioxide and methane) than currently exists in the entire atmosphere. Methane is more than 20 times more potent at trapping heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. Some studies have linked massive releases of methane to the biggest mass extinctions in Earth history.

Needless to say, it’s a region that scientists are following closely. It’s not likely that there will be a rapid, catastrophic release of methane from Arctic permafrost, but gradual methane farts (of the sort that this hole represents) could gradually escalate in the coming years due to global warming. The thing is, the Arctic is so remote that it’s difficult to get good numbers on how much methane is being released. For that reason, the Arctic continually surprises scientists, just like last week.

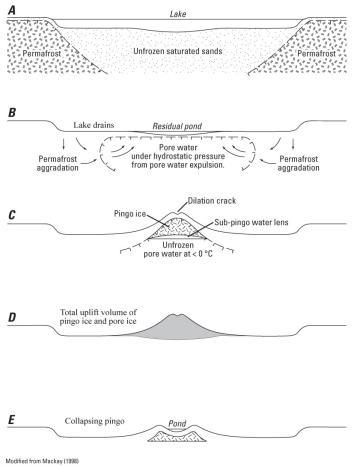

One leading theory says that a pingo—an uplift of frozen ground linked to ancient Arctic lakes—may be at work here. This unique type of landform appears only in permafrost regions.

Image: U.S. Geological Survey

In this case, the holes could have been caused by an unusually large pingo, which have been known to explode, thanks to melting permafrost. This theory was put forth by an Australian polar scientist before the Russian team arrived at the first hole. From the Sydney Morning Herald:

“We’re seeing much more activity in permafrost areas than we’ve seen in the historical past. A lot of this relates to this high degree of warming around these high arctic areas which are experiencing some of the highest rates of warming on earth,” Chris Fogwill told the Sydney Morning Herald.

In short, more global warming means more pingos. Apparently, exploding permafrost is now a thing. Thanks, climate change!

Update, July 31, 2014: Since this post was published, there’s been new (and definitive) evidence released that the Siberian holes were created via methane released from warming permafrost, not a pingo as had been hypothesized earlier. Today, the journal Nature published an interview with archaeologist Andrei Plekhanov and his scientific team, who investigated the first hole. That team measured methane concentrations up to 50,000 times standard levels inside the crater:

Plekhanov and his team believe that it is linked to the abnormally hot Yamal summers of 2012 and 2013, which were warmer than usual by an average of about 5°C. As temperatures rose, the researchers suggest, permafrost thawed and collapsed, releasing methane that had been trapped in the icy ground.

Last week, the New York Times’ Andrew Revkin interviewed a Russian scientist who had also visited the hole and came to similar conclusions.