Computers can trounce humans in Jeopardy! and chess, but robots—try as they may—are decidedly unathletic. Why is that?

On Thursday, June 12, just before the opening game of the 2014 World Cup, University of Pennsylvania professor Daniel D. Lee and some of his champion soccer robots visited the New America Foundation in Washington, D.C., to talk about the challenges, and purpose, of getting machines in the game.

The Future Tense event began with Lee—director of the GRASP (General Robotics Automation, Sensing, Perception) Lab at Penn—giving a brief presentation about robot soccer, and robotics more widely. Lee’s been involved with RoboCup, the robot soccer equivalent of the World Cup, since 2003. RoboCup’s stated goal is to have its championship machines play a competitive match with human World Cup winners by 2050, and while we’re still far from that goal, Lee says that the machines have improved tremendously. “When we started with robot soccer, it looked more like 5-year-old soccer … all the robots would kind of scamper after it,” he said. “The robot gets the ball, [but] they don’t know which direction the goal is, so they kind of randomly kick it. …”

According to Lee, there are three main ingredients to make a robot perform: perception, planning, and action. The robot has to perceive the problem, decide what to do about it, and then implement that plan. Humans involved with sports have to do something similar, Lee said: The difference between a good athlete and a sports-loving nerd is the ability to do all three of those elements, instead of just one or two of them.

All of this research has real purpose beyond having fun. Lee noted that robot soccer is a great way to get students enthused about robotics. Moreover, his lab has applied their robot soccer work to other robotics work that may be more applicable to daily life—like DARPA’s self-driving car competition in 2007 or the DARPA challenge to create humanoid robots that can help after disasters like Fukushima.

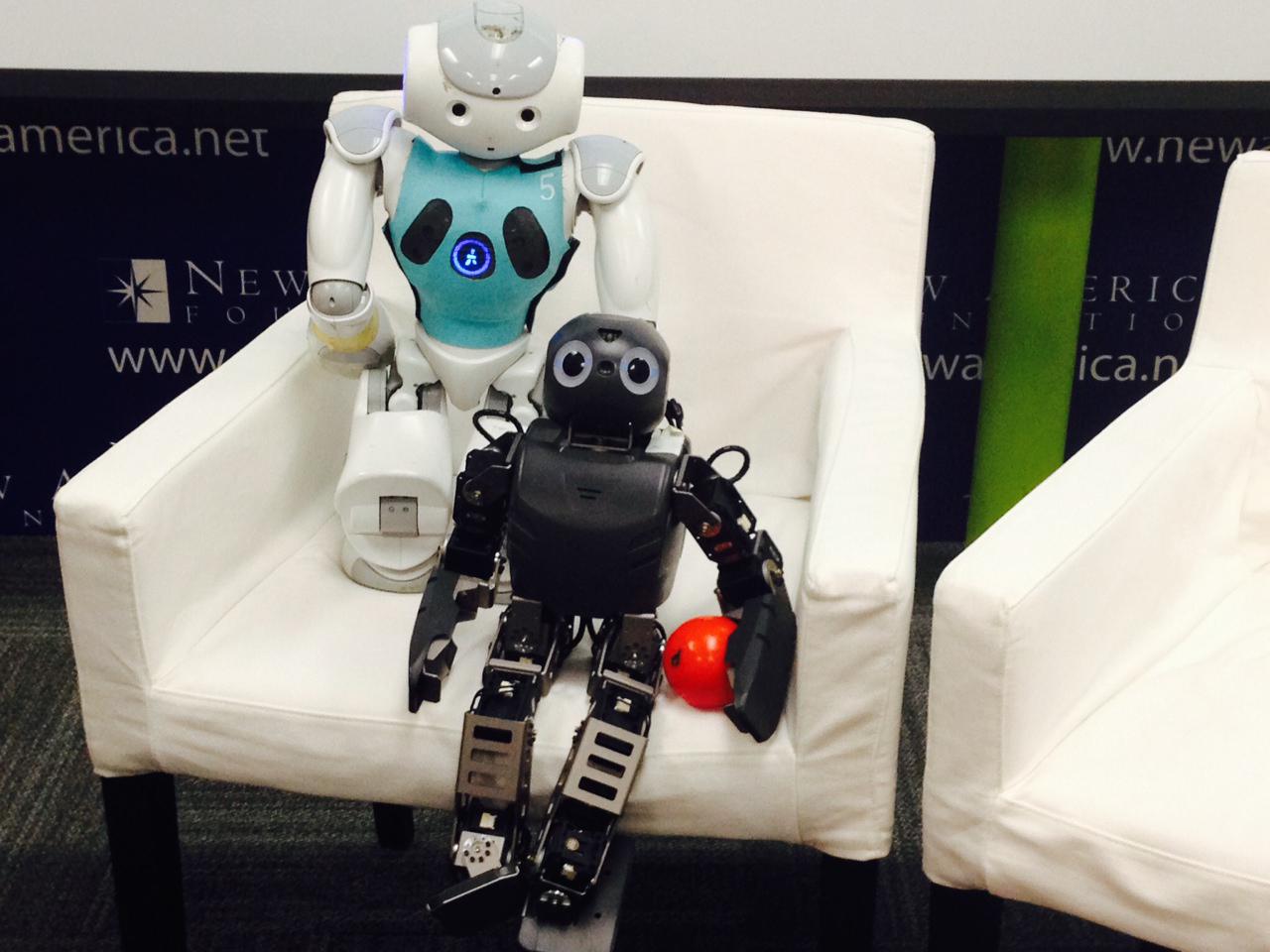

After Lee’s brief presentation, four of his Penn students helped him show off their bots for the crowd. They brought with them two Nao robots and two Darwin robots, all of which toddled around the stage, trying to find and kick a small orange ball. Lee knocked a couple of the robots down so that they could demonstrate their ability to get back up—and the crowd let out a bit of an “Awww.” As the machines bumped into one another, and as Lee and his students picked up wanderers to make sure that they didn’t fall off the stage, the audience laughed and took pictures.

When the demonstration ended, Slate executive editor and “Hang Up and Listen” host Josh Levin joined Lee for a brief discussion about robotics and sports. “We think of machines as being better than us in a lot of things—chess, Jeopardy!” Lee said. “Humans are still much better at something we consider natural,” like running. “There’s certain things that take you 20 years of school to learn that are easy for a machine to do.” Speaking of “natural” challenges, Lee says that future RoboCups may involve having robots play outside, where they’ll have to deal with variable lighting and uneven terrain.

For now, the robots are an adorable example of how technology still can’t best humans in everything. “People really are rooting for these guys and they want them to succeed,” Josh said, referring to the crowd’s enthusiasm for the machines. When the discussion ended, the big screen in the conference room turned to the first game of the (human) World Cup for a viewing party—but the audience members seemed more interested in taking pictures of themselves with the robots.