This piece originally appeared in New America’s Weekly Wonk.

Of all Silicon Valley’s legislative goals, it seemed as if moves to club the patent trolls had the best chance of success. But now that momentum has stalled, what’s next?

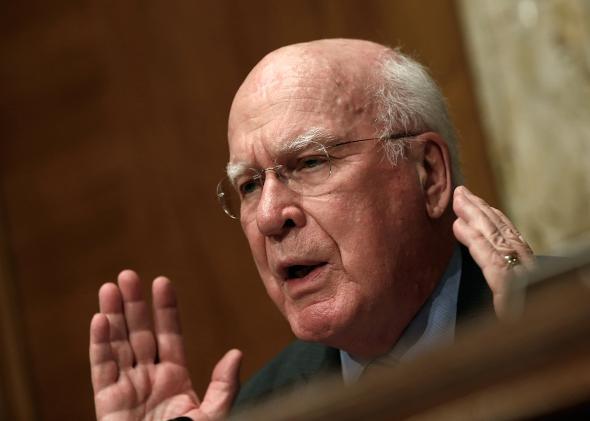

Patent reform advocates expected that the Patent Transparency and Improvements Act, which would have curbed patent trolls by promoting greater transparency around patent ownership and allowing for fee-shifting (making the losing party pay the winner’s fees), would make it into mark-up last Thursday. But on Wednesday morning the news came: Senate judiciary committee chairman Patrick Leahy, who introduced the bill, would be taking it off the agenda.

Leahy’s bill had support from groups as varied as the National Restaurant Association and Electronic Frontier Foundation due to the dulling effect patent trolls, formally called non-practicing entities, have on American businesses. NPEs acquire patents rather than creating products themselves and use aggressive litigation tactics to extract payments from supposed infringers.

While Apple, Amazon, and other tech giants are constant defendants (and plaintiffs) of patent lawsuits, 55 percent of companies targeted by vague, intimidating demand letters from NPEs make $10 million per year or less, and they often pay up to avoid the financial risk of taking the matter to court. One study found that such threats can badly affect the health of the businesses and estimates of the economic cost of NPEs have ranged from $29 billion to $83 billion annually. Whatever the number, it’s a significant drain on companies that could be spending that cash on R&D or hiring employees.

In a statement, Leahy blamed the bill’s demise on an absence of consensus: “We have heard repeated concerns that the House-passed bill went beyond the scope of addressing patent trolls, and would have severe unintended consequences on legitimate patent holders.” His concerns were echoed by some stakeholders, particularly universities, the bio-tech industry, and pharmaceutical companies.

But Leahy’s move left advocates and even the bill’s co-sponsors surprised. Many blamed Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, who reportedly intervened on behalf of trial lawyer groups who opposed the bill. The failure of the Senate bill is particularly notable given that Congress overwhelmingly passed The Innovation Act last year, a bill that proposed a number of anti-NPE measures, with strong support from the White House.

Passing the Senate’s bill should be a priority given the number of businesses that can’t get across America’s many troll-patrolled bridges. But what chance is there?

Advocates of the bill agree—it’s off the table for the moment and in an election year, its prospects are grim. But Julie Samuels, executive director of start-up advocacy group Engine, advised cautious optimism. “We changed the debate and we’ll continue to do that,” she said. Would the bill have a better chance if its scope were more circumscribed? That’s what was suggested by Leahy’s statement and by groups such as the Coalition for 21st Century Patent Reform, which represents patent holders like General Electric. But Samuels disagreed with Leahy’s premise: The bill was the product of bipartisan negotiation and compromise, she told me. Its scope was sufficiently narrow to target only unreasonable NPE cases.

Leahy’s decision was a setback for supporters of reform, but as Samuels pointed out, the path to intellectual property reform is often slow: It took nearly a decade to pass the last significant legislation, the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act. But Samuels also suggested that, no matter who ultimately scuttled the bill, there’s an important lesson here for the tech community: “There are entrenched interests in D.C. that know how to play the game and still wield immense power.”

There’s a lot that can be done in the meantime. “Patent reform is the domain of everybody at this point,” Charles Duan, director of patent reform at Public Knowledge, told me. “The Federal Trade Commission is involved, the White House is involved, the Patent Office is involved. The Senate bill is only one piece of a large puzzle.” To begin with, both the House and Senate have live legislation dealing with one small part of the NPE problem—reforming deceptive, unclear demand letters. The bills have broad support, Duan said, and are widely considered commonsense.

Improving the internal processes of the Patent Office is also a necessity. NPEs now account for the majority of patent lawsuits in the United States, yet only 9.2 percent win their cases at trial, often because they litigate software patents that are obvious and insufficiently novel. Duan told me that industry groups are working behind the scenes with the Patent Office to improve patent quality and clarity. And in recognition of the growing problem, the Supreme Court has taken on five patent cases, including one that asks whether software is even patentable. It’s also indicated its willingness to throw the book at NPEs, recently issuing two rulings that allow judicial discretion to shift fees onto parties bringing frivolous claims.

Advocates of reform are also looking to a forthcoming study by the FTC to provide further ammunition. The FTC’s study aims to examine the effect NPEs are having on American competition and consumers. And while the federal government quibbles, states are taking matters into their own hands. Vermont and Nevada are two that have pushed back on NPEs by filing lawsuits against the more egregious companies and in Vermont’s case, passing legislation aimed at tackling what they call “bad faith” assertion of patent infringement.

Although the Patent Transparency and Improvements Act’s fate remains murky, patent reform advocates should look to the Patent Office, the Supreme Court, and to the states to continue what’s sure to be a long, but vital quest to quash the nefarious activities of NPEs.