In the deep depths of Slate’s comments sections on extreme weather and climate-related blog posts, there lives a fierce debate: Is it “global warming” or “climate change”? Many people use the terms interchangeably, but a new study suggests that one is more effective in conveying the urgency of the problem.

In general, it’s more scientifically accurate to talk about the problem as “climate change.” That term (which dates back to 1956) was in use scientifically almost 20 years before “global warming” (1975). Global warming—the long-term rise in Earth’s average temperature, brought about by the increasing concentration of heat-trapping gases emitted by human activity—is a subset of climate change, which refers to a broader plethora of effects, like ocean acidification, rising sea levels, and crazier weather.

Lumping all these phenomena into “global warming” risks vaulting global temperature to the status of ultimate arbiter on whether scientists’ assessments are accurate. Turns out, climate skeptics have caught on to this, with a (debunked) conspiracy floating around that for some reason, “they” recently changed the name from “global warming” to “climate change” to account for the slower rate of planetary-scale warming in recent years. Therefore, skeptics argue, we shouldn’t have to shift the world’s economy to phase out our primary energy sources.

Scientists typically prefer to talk about “climate change.” That’s because humans don’t “feel’ temperature on a global scale. For people to want to take action, they’ll have to notice and understand local changes, so the reasoning goes. For decades now, scientists and climate communicators have spent untold effort in demonstrating the link between rising greenhouse gas concentrations and the countless less well-known aspects of “climate change” that are much more personal than numbers on a global temperature chart. But “climate change” is a complex and nebulous term, with less vivid imagery than “global warming.”

In 2002, Republican pollster Frank Luntz noted: “While global warming has catastrophic connotations attached to it, climate change suggests a more controllable and less emotional challenge.”

So, what matters more? Scientific accuracy, or word choice?

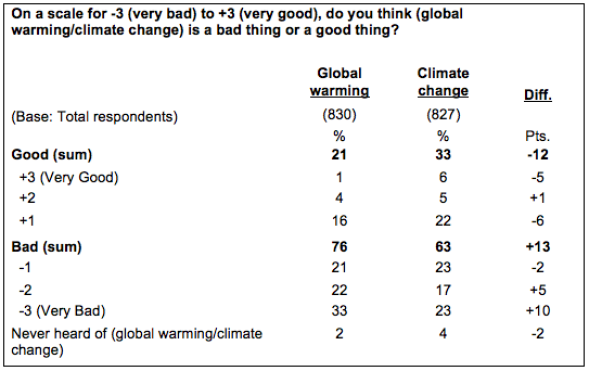

A new study (PDF) released Tuesday tackles these very questions. By randomly swapping out the words “global warming” for “climate change” in an otherwise identical survey, the authors discovered some surprising results. The study was conducted by scientists at Yale and George Mason University and found that for many Americans, they are not the same thing:

Global warming and climate change are often not synonymous—they mean different things to different people—and activate different sets of beliefs, feelings, and behaviors, as well as different degrees of urgency about the need to respond.

The study found that over the last 10 years, Americans were much more likely to use “global warming” as a search term (versus “climate change”) on Google. They’re also twice as likely to use it in conversation. It’s clear that global warming is a term we use more often.

The authors of the survey caution that Americans are sometimes fickle in their connotations with political terms. It could be that “climate change” will eventually overtake “global warming” as the preferred phrase for this issue, but for right now, it’s a clear signal. If you want to talk about the future of the planet, “global warming” is the term that resonates.

In general, “global warming” elicits a much stronger response (especially among independents, who presumably are more likely to be swing voters on the issue). When confronted with that term, Americans have:

- “Greater certainty that the phenomenon is happening”

- “Greater understanding that human activities are the primary cause”

- “Greater understanding of the scientific consensus”

- “More intense worry about the issue”

- “A greater sense of personal threat”

- “A greater sense of threat to one’s own family”

- “A greater sense of threat to future generations”

- “A greater sense that people in the U.S. are being harmed right now”

- “Higher issue priority ratings for action by the president and Congress”

- “Greater willingness to join a campaign to convince elected officials to take action”

Intriguingly, among Republicans, the study also found that “in several cases, global warming generates stronger feelings of negative affect and stronger perceptions of personal and familial threat.”

What’s more, the term “climate change” may actually reduce engagement by those more politically aligned to favor action on the issue. For example, African Americans (+20 percentage points) and Hispanics (+22) are much more likely to consider “global warming” “a very bad thing” than “climate change.” People aged 31-48 are 19 points more likely to join a campaign to convince elected officials to take action on “global warming” than on “climate change.”

Here’s a case where effective science communication seems more likely by using a term that’s less scientifically precise. In general, people seem to “get” the nuance, immediacy, and importance of this issue by just changing the words used to describe it. That’s enough to convince me to rethink my terminology.