El Niño will weaken this year’s hurricanes and suppress their formation, scientists and officials said during the yearly NOAA hurricane season forecast on Thursday.

The annual outlook anticipates the fewest number of hurricanes since seasonal forecasts started being issued by NOAA in 2001.

A bit of science: Hurricanes form best under conditions of warm ocean water, relatively little change in winds with height in the atmosphere, and many vigorous stormlets emerging off the coast of West Africa. El Niño stacks the odds against hurricanes by increasing wind shear of storms that do form (thereby limiting their potential strength) and tearing apart baby tropical systems that move west from Africa (decreasing the likelihood of storms forming in the first place).

For the first time, the forecast was released in New York City. That’s in deference to Hurricane Sandy’s inundation of parts of the city two seasons ago. Also on Thursday, New York City’s Office of Emergency Management launched a new website, “Know Your Zone,” to help promote changes in hurricane season preparedness policies implemented since Sandy. (Gone are the lettered “Zone A, B, & C,” and in are more finely delineated rainbow color-coded Zones 1-6)

Throughout the presentation, officials reinforced the message of preparedness, despite what looks to be a relatively calm season. “As we saw with Sandy in 2012, it only takes one destructive storm to make for a very bad season,” said NOAA administrator Kathy Sullivan.

Partly in response to Sandy’s record storm-surge flooding, this year hurricane forecasters are launching a new graphical storm surge visualization that will accompany forecasts of a potentially landfalling storm. For the first time, forecasters will display potential “worst case scenario” flooding above ground level in map form, taking into account tides and anticipated surge, color-coding areas that have a 1-in-10 or greater chance of flooding. Storm surge is already the deadliest aspect of hurricanes, and with climate change causing rising sea levels, “this hazard to our coastlines will worsen in the decades ahead,” according to Sullivan.

Hurricane forecasters are also implementing improvements this season to short-term models, using computer upgrades paid for by the Hurricane Sandy supplemental relief package passed by Congress in 2013. The resolution of NOAA’s flagship Global Forecast System (GFS) model will soon double. “The new experimental version of this model would have been able to predict the path of Sandy up to seven days in advance. At the time, the [existing] operational model forecast turned the storm out to sea,” said National Weather Service director Louis Uccellini. Improvements to an even higher-resolution model, the HWRF, were field-tested on Pacific typhoons last season, and the updated version was able to better anticipate the tricky “rapid intensification” phase, according to Uccellini. Intensity forecasting is a holy grail of short-term hurricane forecasting and has long lagged path forecasts. This year’s HWRF model will include Doppler radar data from hurricane hunter aircraft for the first time, now possible thanks to the computer upgrades.

The seasonal outlook doesn’t provide guidance on the possible track or impact of individual storms, but is more of a general assessment of the overall storm-birthing environment that’s expected over the next six months.

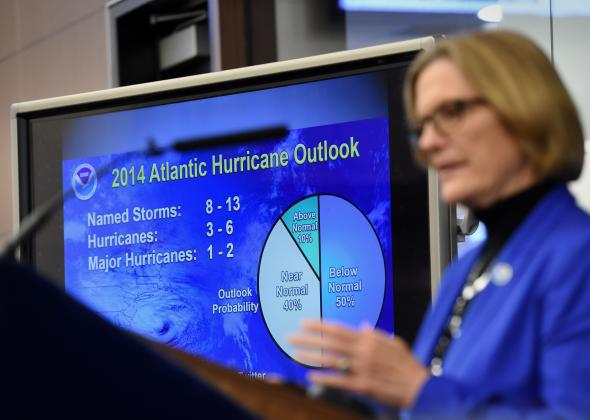

This year’s forecast, like always, is broken down by strength:

A Slate analysis of the past 13 years of NOAA seasonal hurricane forecasts showed that they’re right just about as often as they’re wrong. Over that time span, forecasters issued 39 outlooks (one each year for total storm number, number of hurricanes, and number of major hurricanes). Eighteen of those were spot on, with end-of-season activity falling within the range given before the season began. Nine of the forecasts anticipated too much activity, 12 too little (most notably the record 2005 season that featured Hurricane Katrina’s landfall in New Orleans).

That’s changing, though. While last season’s forecast was an overestimate, during the last five years, seasonal forecasts have improved on average, relative to the early part of last decade when seasonal forecasts first began being issued by NOAA in their current form.

This year’s expected low activity comes on the heels of a quiet 2013 season, which was the first without a major hurricane (Category 3 or stronger) since 1994. A major hurricane hasn’t made landfall in the United States since Wilma on Oct 24, 2005, the longest such drought since at least 1900.

Some took a less even-handed approach to raising attention to this year’s hurricane season. In what can only be interpreted as a desperate bid to drive clicks, the Weather Channel (which has undergone quite a change over the last few months, from impromptu Congressional lobbyists and reality TV central to corporate appeasers and old-school weather nerd headquarters) briefly fielded this whopper of a headline:

Screenshot from Weather.com

Of course, the only good a headline like that can bring is to further alienate readers from actual, hard-fought science. There’s absolutely nothing shocking about today’s seasonal hurricane forecast.

The egregious headline was met with Twitter rage by weather nerds:

But to TWC’s credit, the headline was soon changed to “What’s Ahead for Hurricane Season.”