Although 50 percent of Internet users are concerned about the amount of their personal information available online, getting them to actually read privacy notices is almost impossible.

And that’s not entirely their fault. Since the dawn of the Internet, the design of privacy notices has remained much the same—miles of dense print that it would take a heroic effort to read. In fact, Aleecia McDonald and Lorrie Cranor calculated in 2008 that it would take an individual American an average of 244 hours to read the privacy notices of all the sites they visit annually—and it’s doubtful that the situation’s gotten any better in the last six years.

Most sites also make it easy to ignore their policies and apps tend to serve their notices in such a way that users skip past them as quickly as possible. Admit it: We’ve all clicked “agree” without reading the privacy policy when downloading a Google Maps update.

But some states are pushing back. In 2003, the California Online Privacy Protection Act was the first law in the United States to require digital companies and websites to display a privacy notice and abide by it. And late last year, the act was amended to force companies to disclose details about their tracking of users across websites. To help companies comply with their new privacy notice requirements, the California Department of Justice’s attorney general, Kamala D. Harris, recently issued guidelines that outline recommended practices such avoiding jargon and being more specific about the type of information collected.

The California DOJ’s new guidelines also want websites to overhaul how they direct people to the privacy notice. They ask sites to use a clear link on their homepage, to “[m]ake the link conspicuous by using larger type than the surrounding text, contrasting color or symbols that call attention to it.” Or in the case of mobile apps, make the policy available on the platform page.

This is worthy advice (although the guidelines are not enforceable), but the main hurdle remains—getting people to read and understand the damn thing. Cranor, an associate professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University, wrote in a later paper: “Even when information is available, processing this information may be more burdensome than is feasible for a continual process that is supposed to occur in the background, as a secondary task as we go about our daily living.” To that end, perhaps we should be rethinking the manner in which we serve this information up to internet users?

The guidelines mention a few formats that might be useful: First, online privacy notices could be standardized into a grid format, much like the neat, digestible nutrition information labels we’re all familiar with. Listing, for example, the type of personal identifying information collected, the third parties it’s shared with, and how long it’s held for, for easy comparison with the policies of other sites.

There are obvious problems with the grid format, however—the sheer complexity of most privacy policies would be difficult to render so simply and these grids might not be particularly readable on tiny smartphone screens. However, it’s been suggested that the use of privacy icons that have the same meaning across platforms could be a useful compromise. For example, Apple uses a geolocation symbol when any app is accessing a user’s location.

So how about “just-in-time”, in-context pop-up notices, as the California DOJ’s guidelines also suggest (and as supported by the FTC)? Just-in-time notices serve up privacy information, one bite at a time. They’re usually accompanied by a consent request at the time the information is collected. This format would be particularly useful on mobile screens that don’t lend themselves to long text. And they could promote user understanding—according to a 2013 FTC study, in-context disclosures at multiple points allowed participants to better comprehend the implications of sharing information with the service.

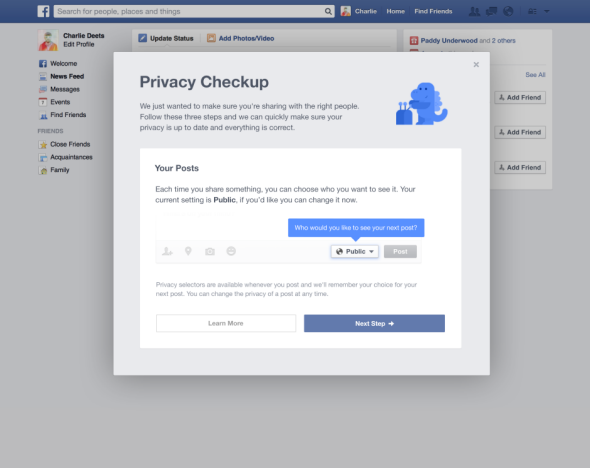

Some companies are beginning to head in the direction of just-in-time notices. Facebook announced on Thursday that it would be using something similar—giving each of its more than 1.23 billion users a “privacy check-up” tool.

Image from Facebook

Facebook’s announcement describes how the tool will walk users through steps to make it clear which apps have access to their data and what private information they’ve included in their profile. The tool will also have a public posting reminder that will ask people to reconfirm the audience they want to share their post with—whether friends-only, public, or otherwise—and a redesigned app control panel, where Facebook users will be able to manage their information-sharing permissions.

The extent to which these just-in-time privacy notices will be used by Facebook remains to be seen. Mike Nowak, a Facebook product manager, told the New York Times that Facebook is concerned that too many of such notices would be intrusive. “We don’t actually like to interrupt people because when they come to Facebook, they are there to interact with their friends, not us,” he told the paper.

But it’s worth pointing out—users are not on Facebook to share personal information with random advertisers either, so the company’s new delivery of privacy notices is a step in the right direction.