Today the Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ) ruled that Google and other search engines can be legally forced to scrub links from search results if they contain personal information about a user who wants them removed. Various European Union bodies, including the European Commission, believe that there is a “right to be forgotten” that should be protected online.

The decision stems from a dispute in which a Spanish man felt that a Google search result violated his right to privacy by revealing through a 1998 auction notice on a third-party website that his former home had been repossessed. The judges said that:

If, following a search made on the basis of a person’s name, the list of results displays a link to a web page which contains information on the person in question, that data subject may approach the operator directly and, where the operator does not grant his request, bring the matter before the competent authorities in order to obtain, under certain conditions, the removal of that link from the list of results.

Though the decision only affects search engine results, it is an indicator of how aggressive the EU may continue to be its pursuit to enshrine the “right to be forgotten.” There are many objections to the right to be forgotten—as my colleague Josh Keating points out, the ruling could actually end up “empower[ing] governments and corporations at the expense of individual users.”

But there’s another major problem: It is impossible to guarantee removal of content from the Internet. Between mirror sites, screenshots, and caching, Internet users anywhere in the world can make a record of anything that is freely available on the Internet before it is removed under legally mandate, and they may retain these records unaware of the legal action.

In fact, a case could be made that this may give people a false sense of security. Sure, if you remove something from Google or Bing, most people won’t be able to find it anymore. But it still exists, and interested parties may be able to find it.

If the ruling stands, people may soon begin wanting to take the next step in the right to be forgotten—demanding that content be taken down. A 2012 report from the European Network and Information Security Agency pointed out the problems with a strict enforcement of the right. “How, ENISA asks, would government force the forgetting of a couple’s photograph when one person wants the photo forgotten and the other doesn’t? And how can data be tracked down and ‘forgotten’ when we don’t even know who has seen or stored it?” Stewart Baker wrote after the report’s release.

This ruling doesn’t go that far yet—but it’s easy to see potential problems on the horizon. The decision highlights the tension between advocating for privacy and advocating for an open Internet/free speech. If you are the victim of a crime that is covered by news media, for example, you might not want to continue to be associated with that crime or be reminded of it years later. This is a compelling reason for people to have some say over what appears in search results for their name.

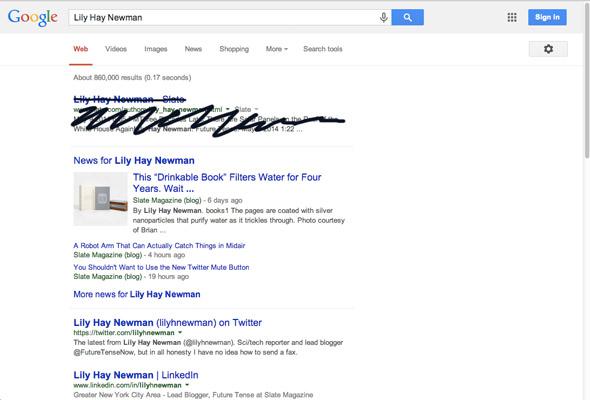

On the other hand, people could abuse this legal avenue by claiming that a search result infringes on their right to privacy so they can do image control after an embarrassing or negative incident that reflects badly on them. The crucial point is how the court will interpret the “certain conditions” in which an EU citizen can bring this type of complaint.

Google spokesman Al Verney told the Wall Street Journal, “This is a disappointing ruling for search engines and online publishers in general,” and added that Google is going to assess the decision’s implications.