A monster late-winter/early-spring storm the likes of which has not seen in the Atlantic Ocean for decades exploded into full bloom on Wednesday morning.

As the big cities of the East Coast of the United States breathed a collective sigh of relief for what might have been, Atlantic Canada is bracing for impact.

Naturally, the Maritime Provinces of Canada have invented their own language to describe this sort of intense weather.

Currently in effect for Nova Scotia: a Les Suetes wind warning—an Anglicization of the French sud est for the strong southeast winds expected—and for Newfoundland, a Wreckhouse wind warning for topographically enhanced gusts up to 110 mph. Wreckhouse winds have been known to blow trains off their tracks.

That’s in addition to the blizzard conditions, storm surge flooding, and wind-blown sea ice crashing ashore on today’s agenda, thanks to a powerful late winter storm that’s ranking among the strongest of the last 50 years.

In this part of Canada, Wednesday’s storm is drawing comparisons to one of the biggest blizzards in Canadian history: White Juan, a storm that followed just a few months after Hurricane Juan’s landfall in late 2003, and dumped almost three feet of snow on Halifax in a single day.

From Environment Canada’s weather gloat of what happened after that storm:

With over 300,000 people, it is now likely the largest city in the world to ever receive such a dump of snow in one day. Buffalo, Fargo and Boise move over! Halifax is the world’s new snow king.

Almost at once, the southern Maritimes became a winter wasteland. For the first time in history, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island declared province-wide states of emergency lasting four days. Halifax issued a nightly nine-hour curfew over three days for all but essential workers in order to give them a fighting chance to clear the snow—estimated to weigh six million tonnes. When Toronto was hit with its “storm of the century” it called in the army, but hardy Maritimers organized neighbourhood work parties to dig themselves out. Streets were deserted for days. Huge drifts reduced four-lane boulevards to narrow walking paths. The Confederation Bridge was closed to all traffic for only the second time ever. The volume and density of the snow was so heavily packed that plows hit mounds of snow and literally bounced back. It took almost a week before bus and ferry service resumed and schools re-opened, leaving students with a record year for the number for lost days due to weather (up to ten in some districts). Miraculously, there were no serious injuries or deaths, just a million unforgettable stories.

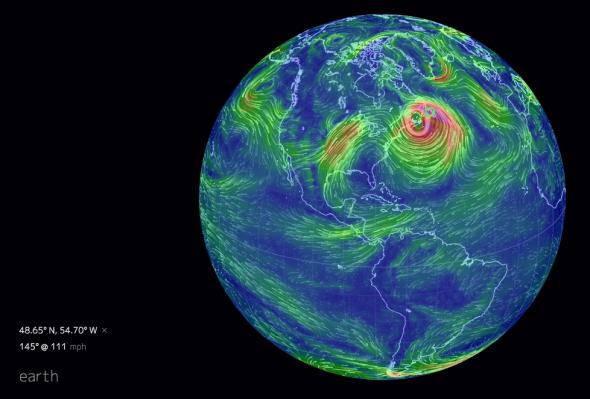

Image via earth.nullschool.net

Meteorologists are now calling this storm White Juan 2, or #juannabe for short.

The hashtag was coined by a legend of Canadian weather forecasting, Peter Coade. A CBC meteorologist for more than 50 years, Coade has seen his share of storms in a region known for some doozies. Coade was recently bestowed the Guinness World Record for “the longest career as a weather forecaster.”

Intrigued, I gave him a call to get his perspective on the impending storm.

Where are you now?

I’m in Halifax. It’s been a great winter here. The only problem is, a lot of people are complaining!

I’ve seen on social media that you’ve called this storm “Juannabe.” Is that because you think it will live up to White Juan, or is it going to fall short?

I picked up the storm from the charts around the middle of last week. When I started looking at it on Saturday, at that time, I was reminded of White Juan. This particular storm is expected to have a lower pressure, though fortunately it’s moving by at a greater rate so the snow won’t be as heavy, generally not more than 50 centimeters (20 inches). We’re going to get a lot of snow, it just doesn’t feel like it at the moment. Here I am talking to you right now, and it’s a bright blue, clear sky.

If this had just popped up on last night’s chart, I wouldn’t be jumping up and down on it. But the thing is, the forecast charts were consistent. All the charts have been unanimous on this one.

So, will the wind be a bigger story than the snow this time around?

If this had been during hurricane season, there might have been more leaves on the trees. There’s no leaves on the trees now, so wind damage won’t be as severe as it could have been. We’re going to have winds over 100 kph (60 mph). That will cause a lot of drifting and blowing of snow.

There are some places over land where gusts could be stronger than that, perhaps up to 160 kph (100 mph), but those winds will be enhanced by local topographical effects. One of those spots is over on Newfoundland, with what they call a Wreckhouse Wind. There’s a set of train tracks below a valley, and in storms like these, the winds would blow trains off the track.

Around here we have to concern ourselves with storm surge. And the Gulf of St. Lawrence is going to be full of ice, shore ice. So places like the north coast of Prince Edward Island could have some damage to homes along the coast from the strong winds pushing that ice onshore.

What’s the one thing you think is most unusual in this storm?

The potential for damage from the wind blowing ice onshore. As meteorologists we generally concern ourselves with what’s falling from the sky, but in this case, we need to think about what’s coming from the ocean, too.

The all-time Halifax low pressure record was set in December 1964 of around 941 millibars. Is that record safe?

It’ll be close. The latest weather models show that this storm might not get below 950. That’s still a pretty hefty low pressure.

In your experience, how rare is this type of storm?

They’re rare. The worst storm you can have on the Atlantic is a winter storm in the northeast. The Gulf Stream is very warm for this time of year. Did you see the movie The Perfect Storm? It’s not one you have every year.

It’s been 10 years since the White Juan storm, which I don’t think got below 960 millibars, and it didn’t come as close to the coast. It is a rare day when you have a pressure as low as that, that’s for sure. This one here is going to be passing within 100 kilometers of the coast.

This interview was lightly edited and condensed.

–

When compared with the first White Juan storm, this storm is significantly rarer, a statistical analysis shows. The Cooperative Institute for Precipitation Systems at Saint Louis University estimates the 2004 storm at an astounding four standard deviation departure from typical late March weather pattern. Wednesday’s storm comes in at greater than five standard deviations—a rarity observed in less than one in a million low pressure centers.

The result is some truly crazy weather. Offshore, winds are gusting in excess of 100 mph, with waves greater than 45 feet. And the storm has now grown to cover much of the western Atlantic Ocean.

My advice? Hunker down, Nova Scotia, and keep the snow shovels handy.