In September, the NSA posted a job listing for a privacy officer. After a summer of revelations about government surveillance overreach, it’s hard to overestimate just how necessary it was for the agency to hire someone whose sole job was to take privacy seriously.

Now, four months later, security consultant Paul Rosenzweig is reporting that the NSA’s pick is Rebecca Richards, currently the acting deputy chief privacy officer for Homeland Security. It seems like a productive step toward better civil liberties oversight in NSA initiatives. But just one quick question. What is a privacy officer? And how much can one actually do to hold the government accountable?

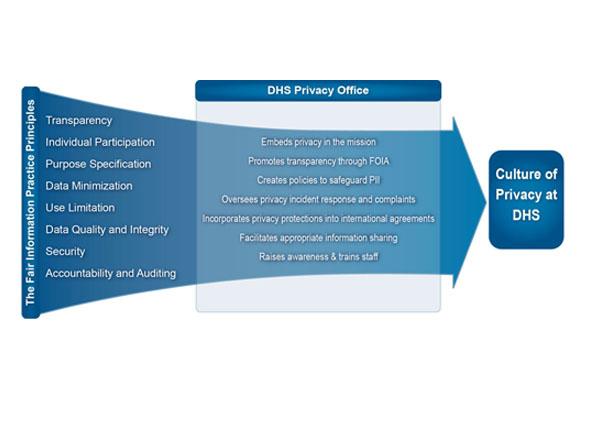

The NSA advertised for someone who would “serve as the primary advisor to the Director of NSA for ensuring that privacy is protected and civil liberties are maintained by all of NSA’s missions, programs, policies and technologies.” So it’s someone who looks broadly at everything the agency is doing and evaluates whether minimum privacy standards are being met, as defined in federal law.

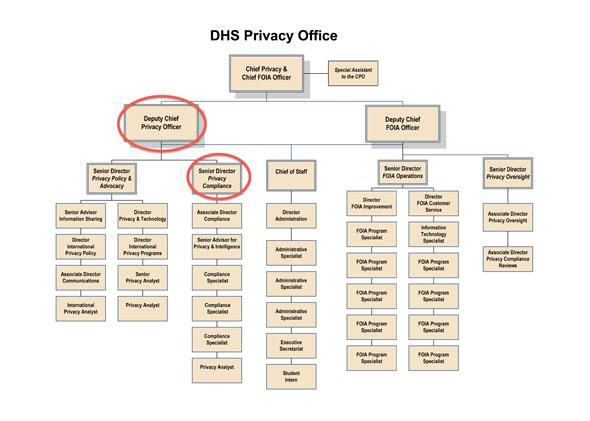

Chart from the Department of Homeland Security.

Pretty much every government agency has a privacy department, even the Department of Education, and they’ve sprung up increasingly in the wake of 9/11 and subsequent Patriot Act abuses. Privacy specialists seem to climb the ranks or bounce around from one agency to another. And they even end up in the private sector, like former Justice Department chief privacy officer Jane Horvath, who left in 2007 to become global privacy counsel for Google and then director of global privacy for Apple.

Each department handles the role a little differently. The chief privacy officer for Homeland Security is focused on five main laws, passed as long ago as 1966 and as recently as 2007. The chief privacy officer “assume[s] primary responsibility for privacy policy, including assuring that the use of technologies sustain, and do not erode, privacy protections relating to the use, collection, and disclosure of personal information.”

Over at the Department of Justice, the chief privacy and civil liberties officer, Erika Brown Lee, came from an antitrust, consumer protection and Federal Trade Commission background and now advises the attorney general about privacy issues related to whatever the DoJ is working. At the DoJ, Brown, “reviews and evaluates Department programs and initiatives and provides Department-wide legal advice and guidance to ensure compliance with applicable privacy laws and policies.”

Privacy officers come to the table with their own opinions, biases, and politics. They aren’t part of initiatives in an agency—they’re outsiders doing oversight of enormous and sometimes controversial projects. But the big question about an NSA privacy officer is whether she will have adequate access to actually provide oversight, no matter how secret something is. To do their job, they must have access to everything. But you can see how people who really believe in the gray area projects they are working on might stay quiet or invoke whatever level of government confidentiality they have to to avoid serious scrutiny from the privacy officer.

If the NSA is just starting its department, it’ll take some time for things to really get moving. And Obama has already made it pretty clear how much he will and won’t do to curtail NSA operations. So good luck Rebecca Richards. The $173,000 salary may not make this job worth it.