Timestamps are convenient. They show up on things like receipts, emails, and text messages (ahem, drunken text messages). There aren’t timestamps for everything, though, and before the digital age they basically just didn’t exist. But researchers at Texas State University won’t take no for an answer.

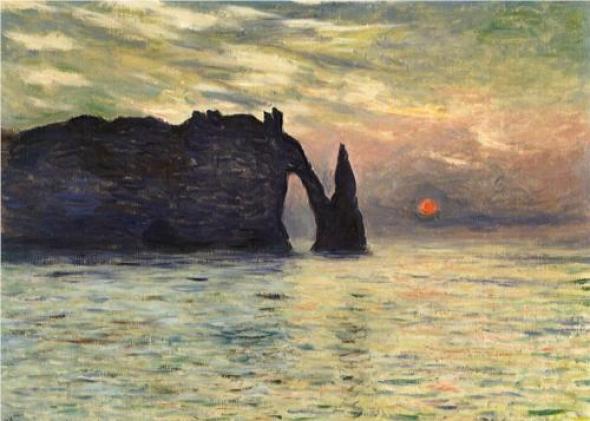

Astrophysicist Donald Olson and his team got the idea that they could date a series of paintings created by Claude Monet by looking at astronomical and geophysical data. The paintings, produced during a three-week trip to Normandy, France, in the winter of 1883, depict different seascapes and skies that gave the researchers clues to work off of. Étretat, Sunset (above) is the only painting in the series that contains a sunset, so on a site visit to Normandy, Olson and his team took angular “declination” measurements to work out the path the sun would have taken to appear to the right of the distinctive rock formation in the painting. Later they used these measurements and planetarium software to compare the modern sky to the 1883 sky and calculate when the sun would have traveled this path.

Assuming a margin for error, the scientists estimated that Monet created the painting between Feb. 3–7. Then they got a little boost. Monet wrote letters during his trip, including on the days in this range—and apparently he was very attentive to tides. By using information from these missives, plus historical weather data and tide charts, the researchers were able to pinpoint Feb. 5, 1883 at 4:53 p.m. local time as the moment Monet was painting, plus or minus one minute. The findings are published in the February issue of Sky & Telescope.

This type of work, known as astronomical chronology, is often criticized for relying on imprecise and unreliable markers. In a 2003 paper, for example, the astronomy historian John Steele wrote that astronomical dating “can easily produce precise and impressive looking results based on invalid assumptions—results so precise and impressive they may not be questioned by scholars in other fields.”

So maybe this isn’t the exact date and time? Who knows. Since not much is hinging on the accuracy of this date, other than the emotional stability of art historians, it seems like the real value in this type of investigation comes from drawing creatively on a range of data sources and developing new tactics for interdisciplinary research. Plus it creates a cool sense of immediacy to imagine Monet painting this particular work at 4:53 p.m. on a Monday in 1883.