This blog post contains spoilers about Ender’s Game.

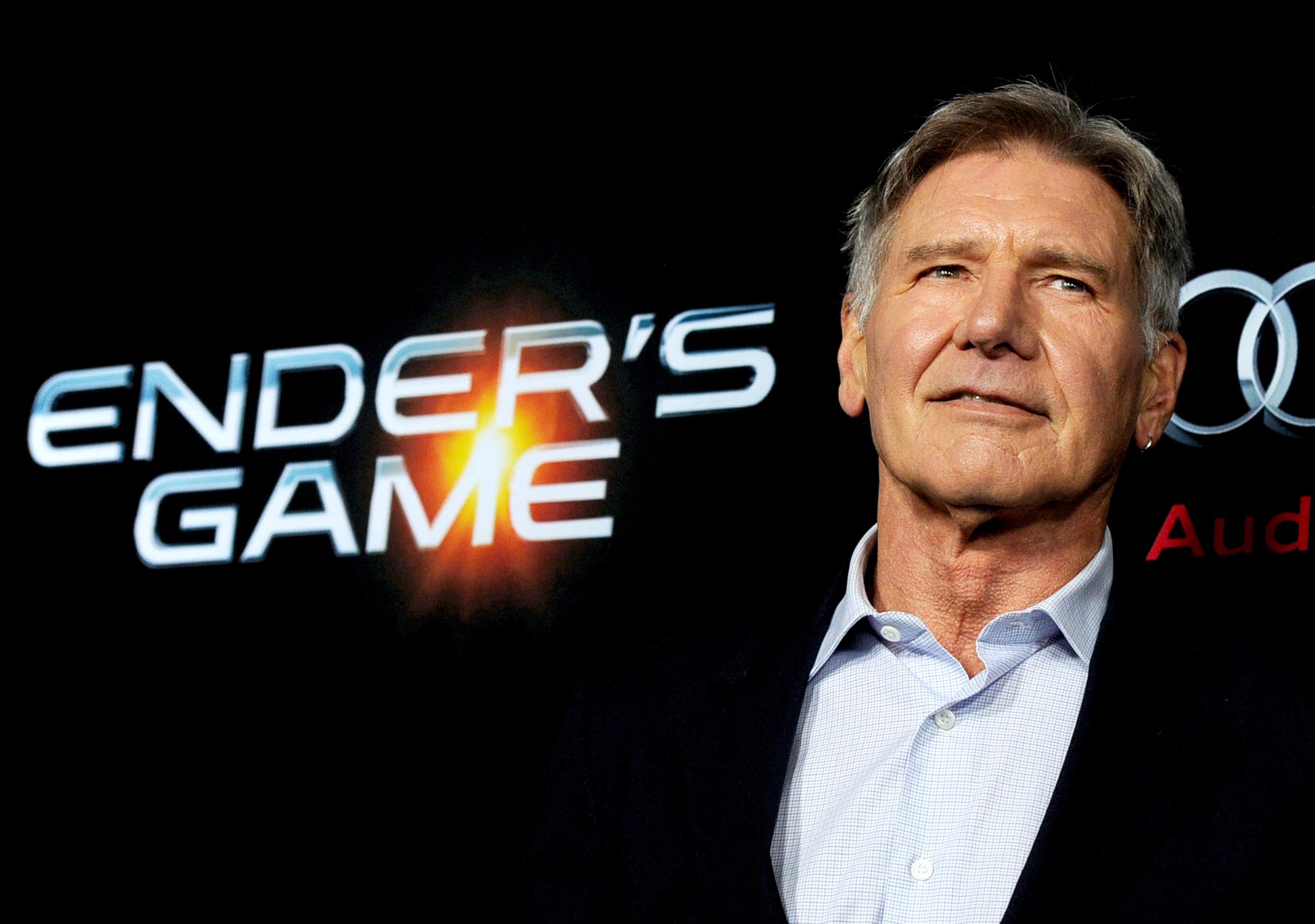

News that Lionsgate is considering a TV series spinoff rather than a sequel to Ender’s Game will not sit well with many fans of the series, but there’s a clear advantage to spending more time with the Battle School featured in the movie, rather than moving along to the quieter story of Speaker for the Dead: the distinctive issues of warfare and officer training in the International Fleet give us an opportunity to spend more time thinking about the technologies of simulation and distance that we’re just now starting to come to grips with in the real world.

Recent studies have shown that drone pilots are subject to psychological trauma just like soldiers in the field. If we thought PTSD was merely about suffering injury and being at risk of death, we were clearly wrong: there is a moral injury that comes from committing violence as well, and the asymmetrical nature of that violence does not eliminate this fact. Trauma is not just what horrors we suffer, but what horrors we commit as well.

This is something that Orson Scott Card addressed compellingly in Ender’s Game, many years before it became the fact of war that it is today. The distance that Ender finds himself in while commanding a distant fleet in no way shields him from the trauma of what he’s done.

Today, technologies like drones and videogame-based military training create similar moral distancing (though unlike Ender, drone pilots know what they’re doing affects real people). The incredible trauma of realization that befalls Ender after the war is “won” is brought home to and by drone pilots on a smaller scale, after each and every operation.

Drone pilots are in something of a half-simulation. Their presence in the field is virtual. The people they see on the screen, of course, are quite real, though, and so this is similar in a one-sided way to Ender’s situation. The enemy has everything to lose in the engagement, but what the pilot has at stake is outside of the engagement: performance reviews, recognition, promotion. It’s no game, but it’s easy enough to see something like a “gamer mode” approach to the activity of hunting and neutralizing the enemy, and not just because you do it with a joystick and a screen: There’s an objective, an outcome, and when you get it, you’re done—and there are no difficult choices about risk to yourself or those under your command. The only time victory is won at a high cost is when a drone is lost or foreign civilians die. But while the costs and benefits to the pilot are game-like, it’s wholly real for those on the other side of the screen.

Amazingly, a recent study has suggested that PTSD in drone pilots might be minimized by humanizing the drone interface. If the drone interface is anthropomorphized—think Siri—then pilots experience less trauma from the decision. And it’s a reasonable hypothesis, one that’s been well studies in social psychology as “diffusion of responsibility.” Probably the most famous experiment on the topic is the Milgram experiment, in which Stanley Milgram sought to understand how the effects of authority and diffusion of responsibility could convince decent people to contribute to genocide, as a great many normal German citizens did in the Shoah. To keep things a bit understated, I’ll merely note that it is questionable whether we should wish to knowingly deploy one of the demonstrated factors contributing to genocide in order to help our soldiers kill with fewer psychological consequences.

War should be horrible and traumatic—but not because this ennobles the spirit, or cultivates the warrior’s virtues, or creates the hardened but fully-rounded character reflective of the entire human condition. War should be horrible and traumatic because otherwise it threatens to become merely a game, or merely a job, and the consequences of warfare where only one side stands to lose are inhumane and unacceptable. As with Ender’s Game, if humanity is worth saving, it must be because humanity is humane; in sacrificing our humanity, we give up the end in order to serve the means.