Josh Goldberg, a junior at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, has attained the ultimate sign of sudden online success: having his website crash because so many people are visiting it.

“Now it’s getting 300,000 unique visitors a day, so like a million hits. Just yesterday alone,” he told the Washington Post’s Timothy B. Lee on Thursday, “there were 385,000 unique visitors from Google Analytics.”

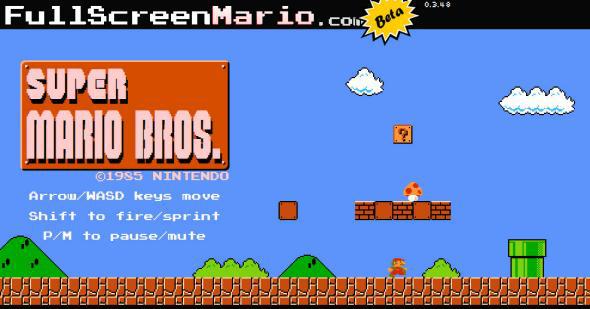

Goldberg’s website? Full Screen Mario, where he’s re-created, brick by brick, the seminal 8-bit video game Super Mario Bros. The appeal of having the original Mario (well, unless you count Mario Bros., which didn’t side-scroll) playable for free anywhere you have an Internet connection and Google’s Chrome browser is obvious. Just look at the nearly 5 million man-hours lost to Pac-Man Fever the day Google transformed the classic arcade game into a homepage Doodle (playable here) for Pac-Man’s 30th birthday.

But Google didn’t invent Pac-Man—Tōru Iwatani and his co-designers at Namco did—and Mr. Goldberg, though you’ve received adulation in the gaming press for Full Screen Mario, starting with the write-up in BoingBoing that made your site famous, take it from the president: You didn’t build that.

Now, Goldberg deserves some credit. He replicated every level of the game by hand, with zero images directly copied from the source. More impressively, he spent months mastering the physics of Mario’s jump, the sine qua non of the whole enterprise. Goldberg’s imitative grunt work follows in a long tradition of creative types copying one another’s work to learn technique and develop their own styles, from Van Gogh’s twists on other artists’ creations to Chaim Potok’s fictional Asher Lev sketching Michelangelo’s David from every angle before making his own masterwork.

I understand if Goldberg felt no pang of guilt when placing Koji Kondo’s instantly recognizable theme into Full Screen Mario, or even when rendering the “© 1985 NINTENDO” from Mario’s title screen onto his version. After all, he didn’t know his exercise would be so successful. “Back in October when I started on it, I didn’t care because I didn’t think it would be a big project,” he told the Post’s Lee. But now that it is, “I honestly don’t know what to do in this situation.”

I do: Shut it down. It’s not yours. Giving away the keys to the (mushroom) kingdom doesn’t mean you own it.

Goldberg seems to realize this, but he still told Lee: “I think it would be a really jerk move for Nintendo to take it down. To take it down would be a spit in the face to Web developers and game enthusiasts everywhere.”

The jerk move is to give something away for free that the rightful owner charges for. Goldberg feels justified doing this because “[t]here are a jillion sites on the Internet that allow you to download the games for free.” He’s right—people can download emulators to illegally play them. “There are sites that have full engines for Gameboy. I haven’t seen a single takedown for those.”

In other words, everyone else is doing it. This excuse doesn’t fly when you’re in kindergarten, so it sure as heck shouldn’t fly when you’re in college. And as Lee learned on Friday, Nintendo does indeed have a problem with Full Screen Mario.

Lee, for his part, agrees with Goldberg that forcing a takedown would be a jerk move, lamenting Friday that “Full Screen Mario is just one example of the ways long copyrights impoverish our gaming culture.” He writes, “Most games make the vast majority of their revenue in the first few years after release. Only a tiny majority of mega-hits such as Super Mario Brothers are still commercially significant after 28 years. And those games have already made their investors’ money back many times over.”

But Mario remains commercially significant for Nintendo. You can download Super Mario Bros. for a few bucks to your Nintendo console or hand-held system, and the company is still adding games to what remains the most consistently excellent series in the medium. Mario, the worldwide ambassador for video games, rivaling and sometimes surpassing Mickey Mouse in recognizability, is intrinsically tied up with Nintendo. For the company to hand its mascot’s pioneering adventure over to the public would mean not only allowing Goldberg to give it away, but Microsoft and Sony to sell it on their gaming systems. If that doesn’t make your heart shudder, maybe you never loved the smiling plumber in the first place.

With Full Screen Mario, Goldberg does best Nintendo’s creation in two ways. The first is that Goldberg has added a level editor, so you can arrange the game’s component parts—coins, question blocks, mushroom-headed Goombas, and so on—to create whatever stage you dare to dream up. More impressively, Goldberg has given Full Screen Mario a random level generator, so that in addition to Super Mario Bros.’ original 32 levels, and whatever levels you and your fellow humans come up with, there are millions more levels for you to play that the computer assembles on demand. The transformation of Super Mario Bros. into its own mini-medium, rather than a defined adventure with a clear ending, is tantalizing, and echoes the huge fun found in other games with randomized levels, like Spelunky, Cloudberry Kingdom, and, well, every game in the roguelike genre. When a game is different every time you play it, it takes a lot longer to get old.

Timothy Geigner at TechDirt, in a Friday blog post, argues that “Allowing users to build their own levels and engage in something like a Minecraft community would only build the brand further.” And you know what? I think he’s right. But that’s Nintendo’s decision to make.

Mr. Goldberg, you’re obviously a talented programmer, and what you’ve done with Full Screen Mario could be a net benefit for Nintendo, in terms of proving concepts the company may very well be all too happy to incorporate into future Marios. I, a terrible programmer who could never accomplish what you have, can only offer some modest but deeply felt advice: Create something of your own. It’s impressive that Full Screen Mario is something that’s happened while you’ve been in college. But you know what else was made in college? Narbacular Drop, a project that would graduate into a little game called Portal. It’s also impressive how much time you’ve spent, as a single person, working on Full Screen Mario. But you know what else was programmed by one person? The beautiful action role-playing game Dust: An Elysian Tale, which indie developer Dean Dodrill did drill into existence over three and a half years.

Show the world something like that, in college or not, on your own or not, and you’ll get money instead of cease-and-desist letters. Which would you rather have?