On Wednesday, the Internet was surprised to learn that a solid 15 percent of Americans aren’t online. A new report by the Pew Internet and American Life Project notes that even though more and more aspects of daily life are moving online, a significant portion of Americans don’t use the Internet. Some of these users choose to opt out, citing a lack of need or interest, but many of the other reasons for staying offline relate to issues of cost and availability. What creates these barriers to connectivity, and what can be done to make sure that more Americans can fully participate in life online if they want to?

Let’s start with affordability. Nineteen percent of respondents who aren’t online cited cost as the main reason. Put simply, access to the Internet in the United States is significantly more expense than almost anywhere else, even when you factor for cost of living and purchasing power. Last year, we at the New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute conducted a survey of Internet prices and speeds in cities across the world and found that American consumers–even in major cities like New York and Los Angeles–tend to pay higher prices for slower speeds compared with consumers abroad. We found that cities with more providers had the lowest Internet prices, a testament to the power of competitive marketplaces. And the places with the best prices don’t take a hands-off approach. They tend to have policies in place to encourage competition and make it easier for new providers to compete with giant incumbents.

Take, for example, unbundling policies, also known as open access. Open-access policies require incumbent broadband providers to lease capacity on their networks to new broadband providers. In places like Japan and France, these policies have allowed innovative new providers like Yahoo BB and Free to compete with incumbents: Both now offer competitively priced Internet connections of 100 megabytes per second (mbps) or more. For comparison, the average speed in the United States is around 15 mbps, while a 100 mbps connection in Washington, D.C., costs well over $100 a month.

Other strategies for reducing costs include encouraging municipal broadband networks, which have spurred competition in places like Lafayette, La. After a high-speed, municipal network became available to consumers in Lafayette for a lower monthly cost, the incumbent provider, Cox Cable, had to respond. For years, Cox had raised prices every year—but after the municipal network came online, the company kept its prices steady for three years.

And then there are those who want to subscribe to the Internet, but can’t. Seven percent of Americans surveyed cited lack of availability or access as the reason for not using the Internet. Although high-speed Internet may seem ubiquitous to those living in big cities or affluent areas, the fact remains that in many parts of the United States, access to the Web is still hard to come by. According to the FCC, 19 million Americans still don’t have access to high-speed Internet in their communities at all. Many of these unconnected individuals live in underserved communities or hard-to-reach places, where ISPs have little financial incentive to build infrastructure and offer service. It’s not too surprising that Pew found a higher percentage of people living in rural communities and from low-income households were offline–they’re more likely to live in areas that don’t have service (not the mention the fact that when service is available, it’s often prohibitively expensive).

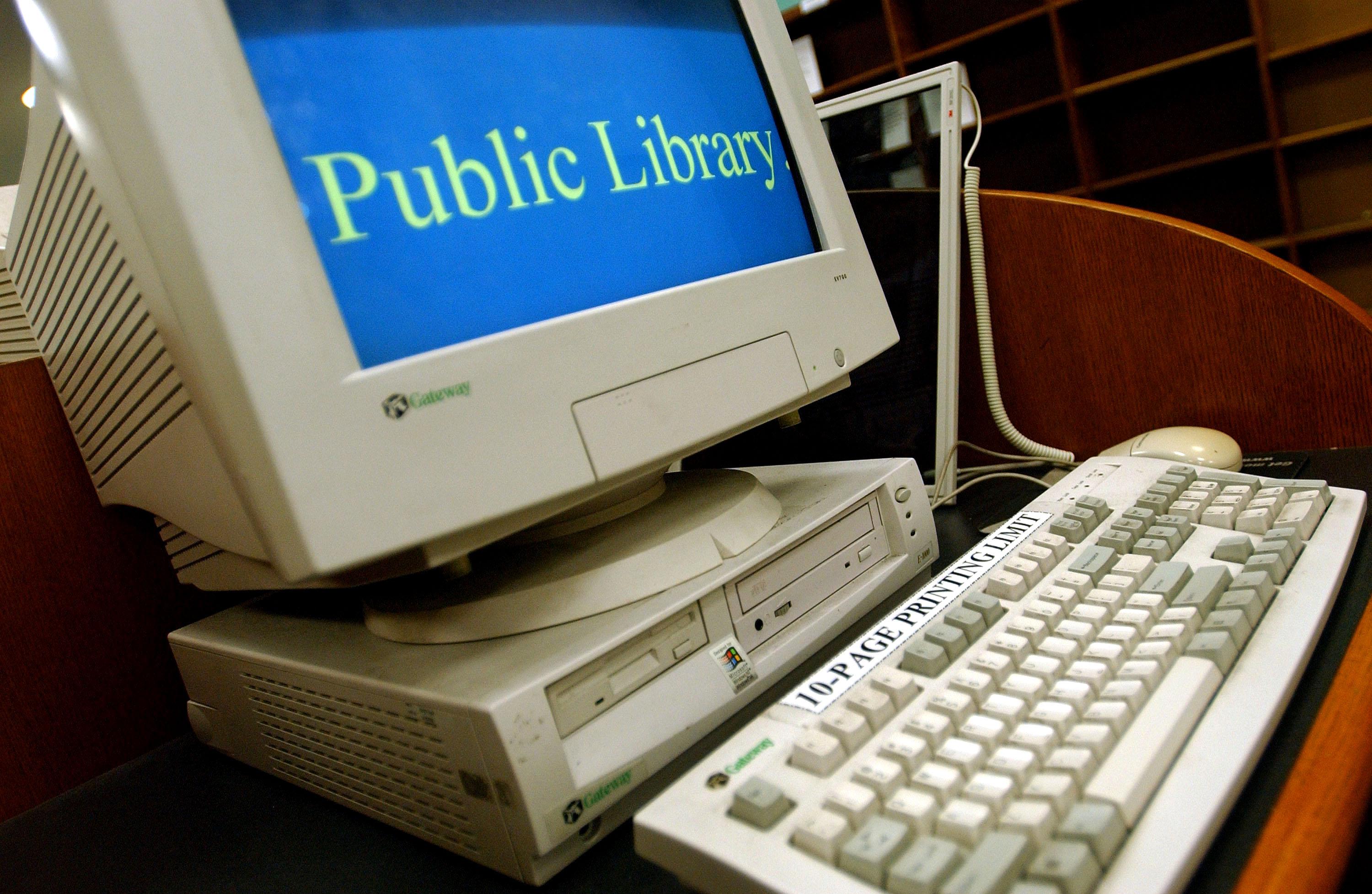

Meanwhile, 9 percent those who do use the Internet reported to Pew that they actually don’t have home access. This demonstrates just how important it is to create and maintain alternative ways of connecting, such as going to a library or a school to use the Internet. These institutions, in turn, may have relied on federal programs like the Broadband Technology Opportunities Program grants to help them provide access and training and programs like E-rate to subsidize connectivity, as well as local government support.

The total number of offline Americans has shrunk in the past few years. But cost and access have also become more prominent reasons that the remaining unconnected individuals still aren’t online. In 2007, Pew reported that 11 percent of offline Americans couldn’t afford it; in 2013, that group represented 19 percent of respondents (down slightly from 21 percent in 2010). While availability is not as significant a barrier as it was in 2007, things have not gotten better in the past three years. Lack of access prevented 6 percent of offline Americans from connecting in 2010, and it rose to 7 percent in 2013.

While the Pew report may show that the percentage of Americans who find themselves on the wrong side of the digital divide is shrinking, the numbers are still significant. That’s why we need the government to actively implement policies that promote competition and support for programs that help individuals and institutions receive affordable access no matter where they live.