Good news, everyone! Journalism is still going to be around 1,000 years from now.

It will be, at least, if the next millennium is anything like the world imagined by Futurama, the beloved animated television series set to end Sept. 4 after airing off and on since 1999.

The show chronicles the adventures of Philip J. Fry, a twentysomething pizza delivery guy who accidentally cryogenically freezes himself in 1999, then wakes up in the year 3000. Its real-life run (including a period off-air between 2003 and 2010) covered a period of enormous upheaval in the journalism industry. Futurama serves as a record of this turmoil: As the journalism industry has changed between 1999 and 2013, so, too, have Futurama’s depictions of 31st century information technology.

Since the beginning, Futurama has depicted today’s media at its worst—sensationalist, entertainment-driven, shallow, and exploitative—probably best summed up in this single five-second clip:

In early episodes, we see references to classified advertising in print newspapers.

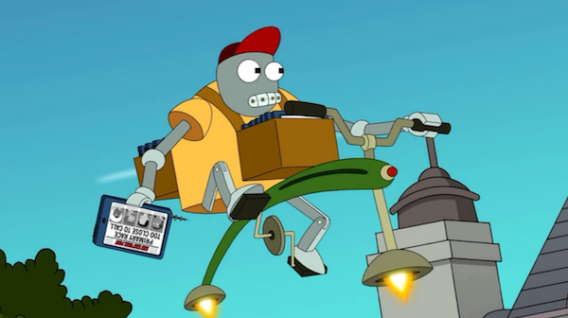

By 2012, a robot on a flying bicycle delivers iPad-like tablets featuring the day’s news to people’s front doors.

Still from Futurama © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

In an episode that aired in 2000, Beijing Bugle reporter Scoop Chang stands up at a press conference holding a reporter’s notebook and a pencil.

Still from Futurama © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

A decade later, Chang returns—this time holding up what looks like an iPhone—and introduces himself as the New New York Times’ “online podcast blog comments editor.” (In an episode that aired earlier this summer, Chang had changed jobs yet again, this time working for New New York magazine as “Kosher recipes editor, iPad edition,” according to a script transcript.)

Still from Futurama © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

More recent episodes of Futurama parody the popularity and influence of the social Web—Twitcher and Facebag are the platforms of the 31st century—whereas the earliest episodes barely mentioned the Internet. One of the first such references was in “A Big Piece of Garbage” (1999), when Professor Farnsworth mentions a deposit of “America Online floppy disks” in a ball of ancient garbage.

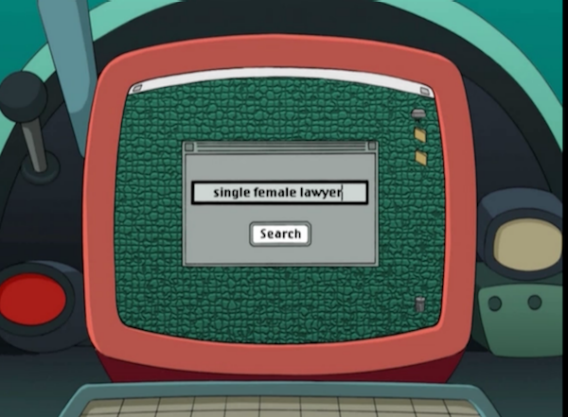

In Season 2, we see the gang’s first online search, yet the computer interface is a 1990s-era Mac and the search-result is more newspaper microfiche than native Web.

Still from Futurama © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

In early episodes, references to CDs and depictions of VHS tapes abound.

Still from Futurama © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

By 2010, Futurama addressed the dawn of the mobile Internet age, including in one episode that focused on the gang’s obsession with the new “eyePhone.”

“No wonder traditional media is dead,” Fry says as he’s watching a webisode on his eyePhone. Smart-aleck robot Bender mocks him for choosing a format that isn’t more interactive. “Enjoy your outdated format, grandma. Nowadays cool kids like me mash up our own phoneisodes.”

And while print newspapers remain curiously ubiquitous in the 31st century, Futurama has had flashes of prescience about tech developments. The voice-commanded eyePhone, for example, is more Google Glass than iPhone.

Still from Futurama © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

In 2000, the show predicted drone video cameras:

Still from Futurama © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

Even back in 1999, Futurama dreamed up functionalities of now-emerging virtual-reality technologies. There’s a montage in the second episode of the first season that shows an amusement park where one character is playing skeeball, another is playing virtual skeeball, and a third is playing virtual virtual skeeball. Absurdly meta? Maybe. But it’s not unlike Oculus Rift’s concept for a virtual reality movie theater experience.

Still from Futurama © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

Plenty of Futurama’s earlier references to media don’t hold up after a decade, let alone for a millenium. But watch enough time-travel flicks, and you begin to experience the delightful incongruity of seeing them age.

For instance, the once-present of Back to the Future’s 1985 is dated today, while some aspects of the trilogy’s once-future in 2015 don’t seem so odd anymore. There’s a scene in Back to the Future II in which Marty McFly visits an antique shop in the year 2015. It’s filled with items that were contemporary in the 1980s, when the movie was released. But today those same items—a lava lamp, a 1980s computer, a bulky JVC camcorder, a talking Roger Rabbit doll—actually are antiques.

Early episodes of Futurama have a similar effect, though the show’s writers are at times deliberate about anachronistic technological references. For instance, an outdated flip-phone gets a rotary dial to underscore how old-timey it is.

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

A new device that projects a Princess Leia-esque miniature holographic image of the person calling is still called a pager.

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

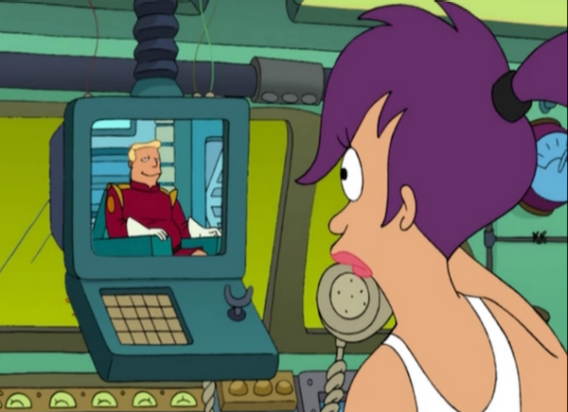

Characters communicate by video call, but monitors are still attached to old-school hand-held phone receivers.

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

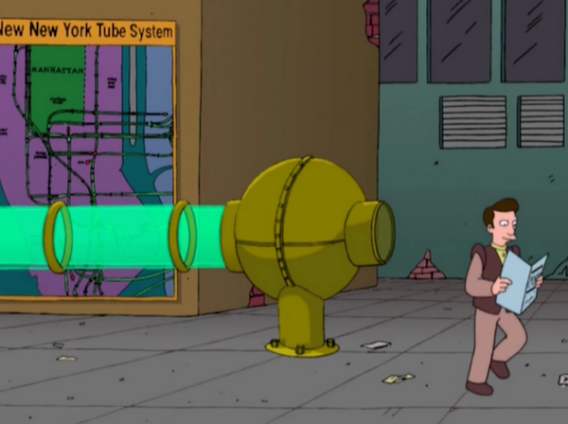

And although the city of New New York has eliminated its subway system in favor of a series of pneumatic tubes, commuters still thumb through the print newspaper while they ride.

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

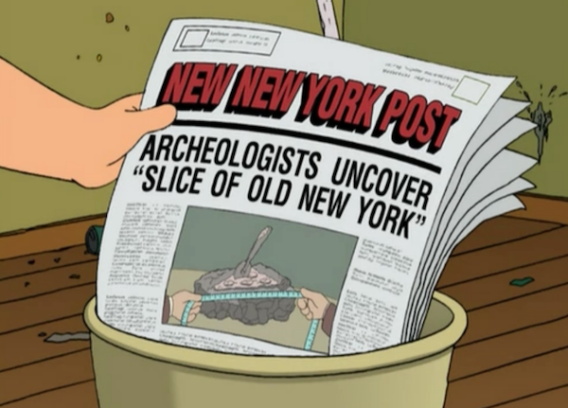

In most cases newspapers are plot devices, including plenty of blink-and-you’ll-miss-it front-page gags.

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

An episode about a paper route is less about newspapers and more about a typical first job. Futurama’s writers revel in simultaneously employing and mocking cliched depictions of journalism.

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

But most of the show’s references to journalism poke fun at the news media of today.

The New Yorker is depicted as stuffy and elitist:

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

Celebrity tabloids are lampooned as exploitative.

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

Media is generally despicable in Futurama’s world, so much so that credible news sources are out of place. In one episode, when Walter Cronkite’s head delivers the news, Bender is disturbed: “This guy’s too trustworthy. What’s his angle?”

In another episode, when Bender becomes a paparazzo, his editor is literally a larva.

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

Futurama lambasts the shallowness of modern campaign coverage by having a moderator respond to a candidate in a presidential debate, “Thank you, Senator, a thoughtful and lucid answer. You will be destroyed! Question 2, the environment: Yes or no?”

Next-millennium news anchors cover a mix of fluff and disaster—sometimes concurrently.

© Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

Yes, news anchors of the future are portrayed as violence obsessed—“Show us the killing skills that have made you a media darling,” a group of robots urges in “Fear of a Bot Planet”—and as unimaginative at selecting stock art as they are today.

Still, the people of the 31st century are overwhelmingly viewers of cable news—and analog at that. There are plenty of shots of snowy television screens. (It’s worth noting that in some early episodes, the gang still has bulky tabletop television. Even the Jetsons had a flatscreen!)

What longtime Futurama viewers already know is that Futurama isn’t really a show about the future. (The series name is a reference to the 1939 New York World’s Fair, according to co-creator Matt Groening.) It uses well-worn science fiction cliches to parody the genre, and is set in the 31st century as a way to satirize the present.

In one memorable exchange, Fry laments the pervasiveness of advertising in the year 3000. Companies are able to implant ads in people’s dreams. One character asks: “Didn’t you have ads in the 20th century?” Fry’s response: “Well, sure. But not in our dreams. Only on TV and radio. And in magazines and movies and at ballgames and on buses, and milk cartons and T-shirts, and bananas and written on the sky. But not in dreams, no siree.”

In an episode that aired in 2010, the show addresses privacy concerns of the big data age. A corporate villain rejects the idea of “too much information” being shared online: “It’s exactly the right amount of information! For years I’ve collected personal data with old-fashioned methods like spybots and infosquitoes. But now thanks to Twitcher, morons voluntarily spew out every fact I need to exploit them. Fire direct marketing algorithm!”

Futurama is sharp in its criticisms about the changing media world. What’s remarkable is that even in the context of inventing a distant future, the show didn’t predict the profound disruption in journalism any more than most of the rest of us did.

The technological shifts and innovations we’ve experienced just since 1999 are far richer than many of us could have imagined happening at all.