In the past year, Skype has repeatedly portrayed its Internet phone call service as a secure way to have conversations that can’t be eavesdropped on. But a string of new details suggest that the opposite is true—and that the company secretly worked to help government spies wiretap Skype calls.

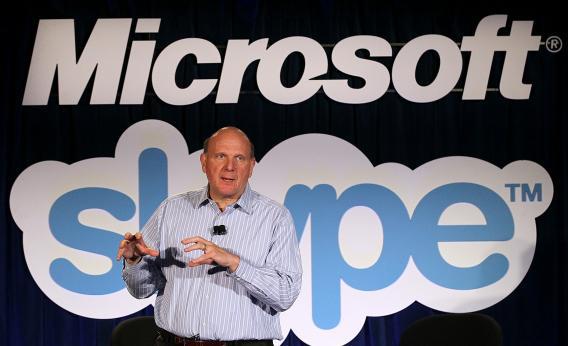

The New York Times reported Thursday that Skype quietly initiated an internal program called “Project Chess” to explore how it could make Skype calls readily available to intelligence agencies and law enforcement officials. The program reportedly began five years ago, before Microsoft acquired Skype in 2011, casting yet more doubt on what now appear to be highly misleading recent statements issued by Microsoft on the subject of Skype’s security. Earlier this month, it was separately revealed by the Washington Post that in 2011, Skype became part of a National Security Agency spy program called PRISM. The Post, citing leaked government documents, reported that the NSA has a “User’s Guide for PRISM Skype Collection” that outlines how it can eavesdrop on any combination of Skype “audio, video, chat, and file transfers.”

These details are important because Skype has previously been extremely evasive on the issue of surveillance. Before it was purchased by Microsoft, Skype representatives openly boasted that its encryption technology meant that the chat service could not be spied on—which made it a popular tool for journalists and activists concerned about government snooping.

But last year, about 14 months after Microsoft announced its takeover of Skype for $8.5 billion, the company flatly refused to answer my repeated questions about its eavesdropping capabilities. I was particularly interested in the relevance of a patent obtained by Microsoft for “legal intercept” technology designed to be used with services like Skype to “silently copy communication transmitted via the communication session.” But answers were not forthcoming. Eventually, Skype’s Mark Gillett was forced to issue a carefully crafted denial—which did not directly address the issue of the patent—dismissing eavesdropping concerns as rooted in “false” and “inaccurate” reporting. In March, Microsoft went further, producing a transparency report that alleviated surveillance fears by claiming that it had not handed over any Skype communications content over to authorities anywhere in the world. Microsoft said in notes accompanying the transparency report that calls made between Skype-Skype users were encrypted peer-to-peer, implying that they did not pass through Microsoft’s central servers and could not be eavesdropped on.

Now, though, the disclosures about PRISM and Project Chess appear to flagrantly discredit Microsoft’s Skype eavesdropping denials. While publicly portraying Skype chats as beyond government intrusion, the company was apparently working to grant U.S. authorities covert access to them. Skype’s Mark Gillett even accused journalists who questioned Skype’s eavesdropping ability of misleading Skype users about its “approach to user security and privacy”—which now looks like a serious case of hypocrisy. Some technology writers, too, credulously swallowed Skype’s statements about its surveillance capabilities—and criticized reporters, including me, for demanding answers about the extent of the company’s cooperation with the government. But the recent revelations illustrate that you can never be too skeptical, and that blindly trusting large U.S. companies’ public relations claims is unwise in an age of gag orders and secret surveillance programs.

Skype did not respond to a request for comment for this post.