With Robinson Meyer’s massive Twitter rant about “the death of tech blogging,” this feels obvious but worth saying: Declaring things dead—long a popular way for writers to draw attention to themselves—is totally, inescapably dead.

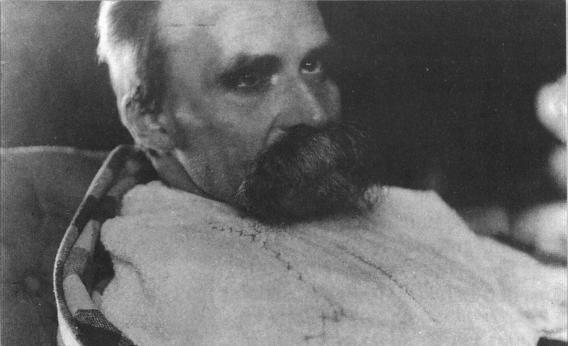

Friedrich Nietzsche established the “declaring things dead” form, when—after trying about 400 other aphorisms in The Gay Science—he struck gold with “God is dead” in 1882. Fifty percent hyperbole, 50 percent trolling. Well played, Nietzsche.

Moving forward a century, Francis Fukuyama declared history dead in 1992. Since 2006, Slate has declared email, the independent bookstore, the American pun, and instant gratification dead. The publication for which Meyer regularly writes, The Atlantic, has killed off television, monogamy, and the shopping mall just in the past few months.

Last month, the Washington Post’s Carlos Lozada catalogued the long list of things that book titles have declared “the end of,” including sex, power, money, and, yes, men. Even things that are clearly alive are now labeled dead. Hey, PC sales are down—that kinda sorta qualifies as “dead.” And hey, some tech blogs now blog about things other than gadgets! R.I.P. tech blogs.

The headline of that Post story: “The end of everything.” If everything is dead, then nothing is. So now, on May 20, 2013, we must solemnly declare that the “death of” genre has expired. It was 131.

“Declaring things dead” will be mourned by all of those desperate writers and editors who shoveled it into headlines, both online and in print. It will be survived by thousands of journalistic clichés, including “Is X Over?” and “Could This Be the End of ____?”